Fewer butterflies seen across the warming, drying landscapes of the American West – Increasing fall temperatures may be a significant driver of declining butterfly populations

By Mike Wolterbeek

4 March 2021

(Nevada Today) – New methods of conservation and management of butterfly habitat may be needed to stem the consistent annual decline in the numbers of butterflies over the past 40 years in the western United States, according to a new study published in the journal Science.

“The widespread butterfly declines highlight the importance of careful management of the lands that we do have control over, including our own backyards where we should use fewer pesticides and choose plants for landscapes that benefit local insects,” Matt Forister, biology professor at the University of Nevada, Reno and lead author of the report in Science, said.

The estimated 1.6% per year decline is consistent with reported declines for other insect groups from other parts of the world. The report is unique in covering a wide area of relatively undeveloped land as compared to, for example, studies from heavily populated areas of western Europe.

“The fact that declines are observed across the undeveloped spaces of the western U.S. means that we cannot assume that insects are okay out there far from direct human influence,” Forister, in the University’s College of Science, said. “And that’s because the influence of climate change is, of course, not geographically restricted.”

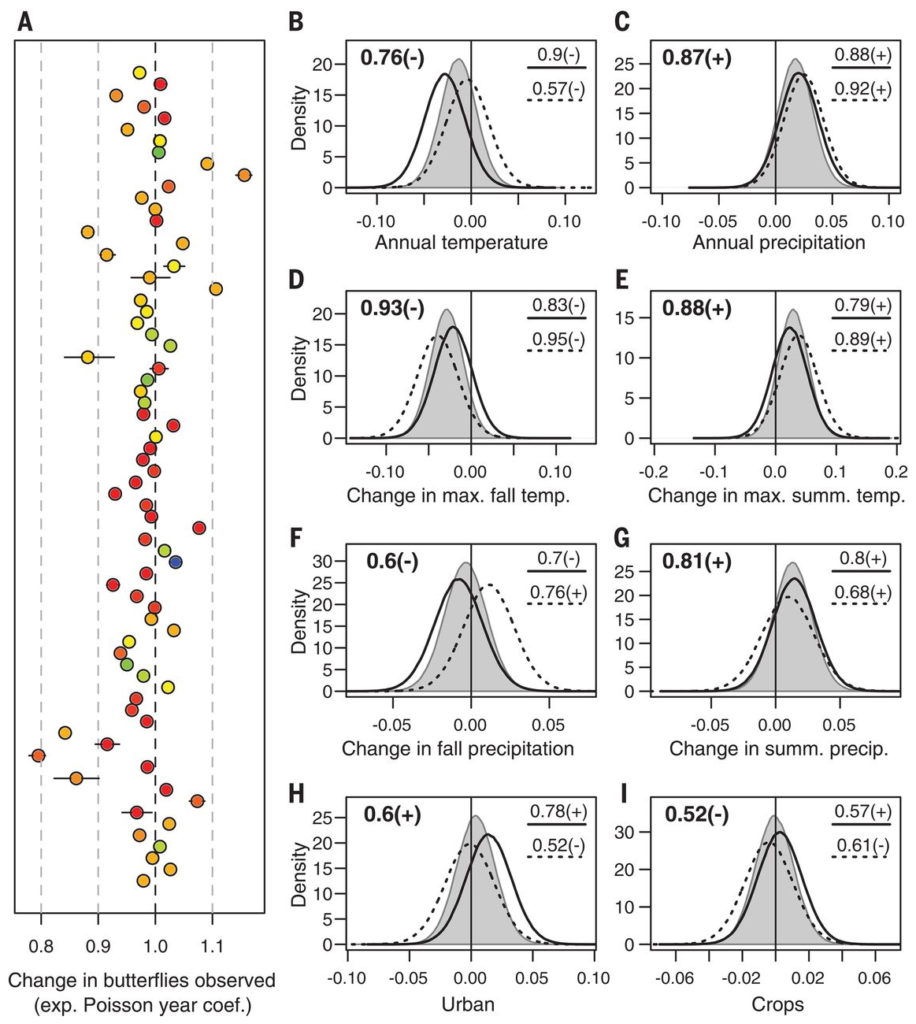

The decline was estimated using data from 72 locations with at least 10 years of data per location and more than 250 butterfly species. The total time span encompassed by the study is 42 years, from 1977 to 2018, and the average length of time series from individual sites was 21 years.

The team considered land use, annual climate and season-specific rates of climate change to find the most influential predictors for the decline. The pervasive declines they found advance the understanding of climate change impacts and suggest a new approach is needed for butterfly conservation in the region, focused on suites of species with similar habitat characteristics or host-plant associations instead of conventional conservation and management practices focused on single species.

“Western butterfly declines are associated with increasing fall temperatures across the U.S. wildlands,” co-author Katy Prudic a biologist from the University of Arizona, said. “Conservation, management and restoration on public lands, especially along cooler riparian areas, will be critical for preventing butterfly declines and extinction.”

Management of developed areas can have immediate benefits for insect populations but the impacts of climate change across all landscapes cannot be ignored, the authors said in the report, and society should not assume that the legal protection of open spaces is sufficient without action to limit the advance of human-caused climate change.

The team used both community scientist and expert-collected data, focusing on the western United States, which is uniquely useful for understanding the effects of climate change on insects. The warming and drying trends observed across different types of land use, everything from major cities to protected national parks, from the coast to inland areas, valleys and mountains, were important for revealing climate impacts.

The three datasets used in the study are the Shapiro transect from Northern California, the North American Butterfly Association network of community scientist count data and the iNaturalist web platform of contributed observations. These three sources encompass more than 450 species of butterflies and are complementary in that they represent varieties of geographic coverage and expertise, long timeframes, and differences in the density of urban and agricultural areas. The Shapiro dataset is expert run, the NABA counts are generated by teams of volunteer or community scientists, and the iNaturalist records are contributed by thousands of nature enthusiasts whose identifications are vetted by a machine learning algorithm and at least two human experts.

“We relied heavily on data from citizen or ‘community’ scientists,” Forister, in the University’s Department of Biology and the Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology program, said. “Volunteers are generating amazing data these days, and we wouldn’t have been able to study as many locations without decades of hard work from hundreds or maybe thousands of people.”

The study published in Science complements other, recent work on insect declines from the University of Nevada, Reno, which have included contributions to a recent special issue in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and one of the first reports of declining insect diversity from a protected forest in Costa Rica.

Participating in the study published in Science, along with Forister and Prudic, were Christopher Halsch, Department of Biology, Program in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology, University of Nevada, Reno; C. C. Nice, Department of Biology, Texas State University; J. A. Fordyce, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville; Thomas E. Dilts, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Science, University of Nevada, Reno; J. C. Oliver, Office of Digital Innovation & Stewardship, University Libraries, University of Arizona, Tucson; J. K. Wilson, School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona, Tucson; A M. Shapiro, Center for Population Biology, University of California, Davis; and J. Glassberg, North American Butterfly Association, and Department of BioSciences, Rice University, Houston, Texas.

Fewer butterflies seen across the warming, drying landscapes of American West

Dramatic Decline in Western Butterfly Populations Linked to Fall Warming

By Rosemary Brandt

4 March 2021

(University of Arizona) – Western butterfly populations are declining at an estimated rate of 1.6% per year, according to a new report published this week in Science. The report looks at more than 450 butterfly species, including the western monarch, whose latest population count revealed a 99.9% decline since the 1980s.

“The monarch population that winters along the West Coast plummeted from several hundred thousand just a few years ago to fewer than 2,000 this past year,” said Katy Prudic, an assistant professor of citizen and data science in the University of Arizona School of Natural Resources and the Environment and a co-author of the report. “Essentially, the western monarch is on the brink of extinction, but what’s most unsettling is they are situated in the middle of the pack, so to speak, in our list of declining butterfly species.”

Declining population groups include butterflies that typically thrive in disturbed and degraded habitats, such as the cabbage white, or Pieris rapae, as well as species with broad migration ranges, such as the West Coast lady, or Vanessa annabella.

The research team sourced more than 40 years of data collected by both expert and community scientists across the western United States to identify the most influential drivers in butterfly declines.

“When we talk about global change, it’s often hard to tease out climate and land use change because they are happening simultaneously,” Prudic said.

“Our report is unique in covering a wide area of relatively undeveloped land as compared to, for example, studies from heavily populated areas of western Europe,” said Matthew Forister, a biology professor at the University of Nevada, Reno and lead author of the article. “The fact that declines are observed across the undeveloped spaces of the western U.S. means that we cannot assume that insects are OK out there far from direct human influence. And that’s because the influence of climate change is, of course, not geographically restricted.”

The takeaway, Prudic said, is western U.S. butterflies are declining quickly, and autumn warming – not spring warming or land use change – is an important contributor to the decline.

Fall is the New … Warm

When it comes to seasonal warming, spring gets a lot of attention, but the warming climate affects temperatures year-round. Fall warming trends have been observed in 230 cities across the U.S., with the greatest fall temperature increases found in much of the Southwest.

“In Arizona, for example, the period between September and November has warmed about 0.2 degrees Fahrenheit per decade since 1895,” said Michael Crimmins, a professor and climate science extension specialist in the UArizona Department of Environmental Science. “Fall temperatures have warmed especially fast since the late 1980s and it’s not clear why.”

Declining butterfly populations have been observed in areas experiencing these fall warming trends across the West, according to the report. The authors suggest fall temperature increases may not only induce physiological stress on butterflies but may influence development and hibernation preparation. Warmer fall temperatures can also reduce the availability of food or host plants, and extend the length of time butterflies’ natural enemies are active. [more]

Dramatic Decline in Western Butterfly Populations Linked to Fall Warming