Will a push for plastics turn Appalachia into next “Cancer Alley”? – “It’s so obvious that they are trying to lock us into fossil fuels”

By Emily Holden

11 October 2019

MONACA, Pennsylvania (The Guardian) – Construction cranes climb into the sky and sprawl across the massive petrochemical facility that will turn a byproduct of fracked gas into plastic on the banks of the Ohio River, just outside Pittsburgh.

Even at a distance, from the car park of a cancer treatment centre on a nearby hilltop, Royal Dutch Shell’s 386-acre site is a behemoth. It will anchor yet more gas, plastics and chemicals infrastructure in the tristate region of Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

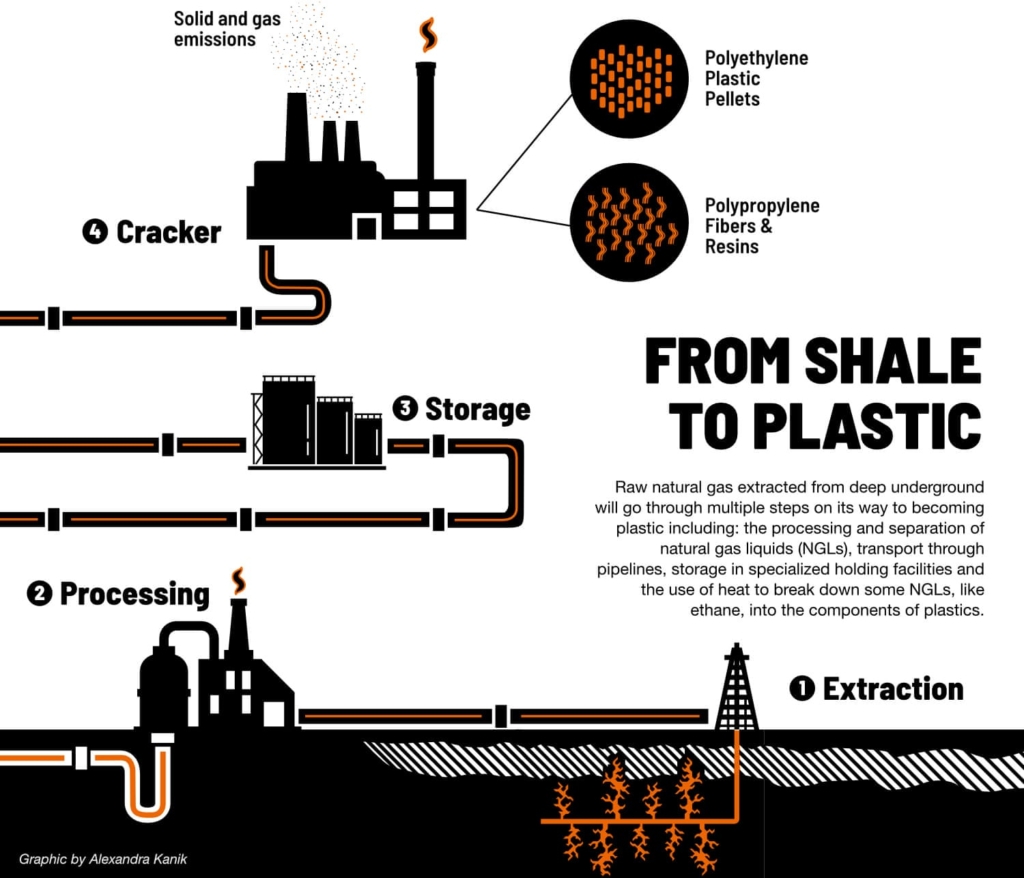

The plant would solidify demand for fracked natural gas and the ethane that comes with it out of the ground. It would make 1.6m tons of plastic and 2.2m tons of globe-heating carbon dioxide annually – roughly the same amount the city of Pittsburgh is trying to eliminate. The facility would also release hundreds of tons of toxic compounds into the air.

As global demand for plastics grows, the buildout of this industry threatens US progress on the climate crisis and clean air.

Opponents say the vast plastics industry will prolong fracking, even after power companies shift further towards renewable power, such as solar and wind. “To me, it’s so obvious that they are trying to lock us into fossil fuels,” said Terrie Baumgardner, a member of the Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community.

At a time when scientists warn humans must stop pulling fossil fuels out of the ground and spewing plastics into the environment, natural gas drilling is booming in Appalachia and the ethane-to-plastics industry there is just getting started. [more]

Will a push for plastics turn Appalachia into next ‘Cancer Alley’?