What the climate’s “new normal” is doing to Lake Superior

By Ron Meador

1 November 2019

Minnesota has shoreline on only one Great Lake, but it happens to be the greatest: largest, clearest, coldest and, until recently, seemingly least vulnerable to various environmental afflictions elsewhere in the five-lake basin.

The world’s biggest lake by surface area, Superior happens to hold one-tenth of the fresh water on the face of the Earth. Its volume equals those of Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario combined, plus several more Eries. Sea kayakers and sailors who travel on Superior like to call it an inland ocean.

There is love in that loose comparison, but also some aptness: Here is a lake that can make its own weather, accommodate ocean-going vessels (and sometimes sinks them), whose resident aquatic species now include emigrants from all over the world thanks to irresponsible handling of ballast water. It’s not only wide but deep; as a newbie kayaker nearly 20 years ago, I was reassured by seasoned companions that the nice thing about paddling Superior is you’re always within a quarter-mile of land – if you count the bottom.

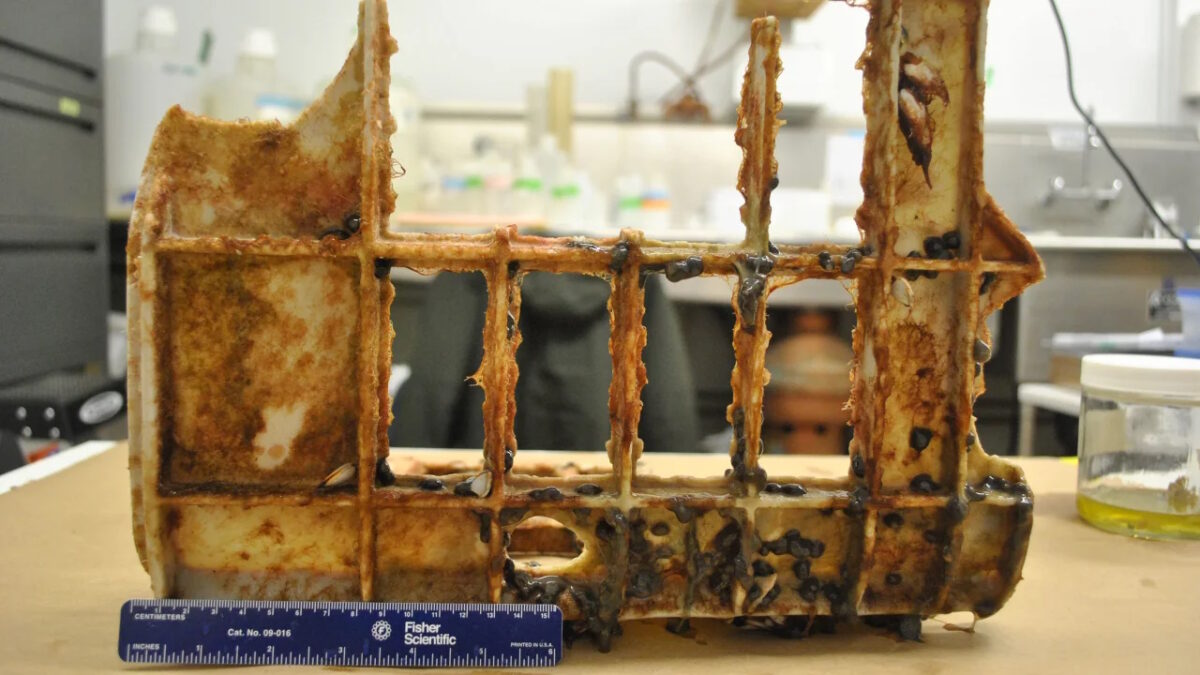

Now the lake and its shoreline communities are experiencing a series of climate impacts that run queasily parallel to the problems of saltwater coasts that have become familiar in recent decades: storms of unusual fierceness and destruction, intensifying rainfall patterns, accelerating coastal erosion and infrastructure losses, overwhelmed wastewater treatment systems, icky (and potentially harmful) algal blooms. [more]