“Their house is on fire”: the pension crisis sweeping the world – “We just have to explain to millennials that their parents might have to move back in with them”

By Josephine Cumbo and Robin Wigglesworth

16 November 2019

LONDON/OSLO (Financial Times) – Jan-Pieter Jansen, a 77-year-old retiree from the Netherlands, had high hopes for a worry-free retirement after having saved diligently into a pension during his working life.

But Mr Jansen, a former manager in the metal industry, has been forced to reappraise his plans after receiving notice from his retirement scheme, one of the Netherland’s biggest industry-sector funds, of plans to cut his pension by up to 10 per cent. Understandably, the news has hit like a sledgehammer.

“This is causing me a lot of stress,” says Mr Jansen, who retired 17 years ago and hoped to use his pension pot to treat his grandchildren and afford good hotels on holidays. “The cuts to my pension will mean thousands of euros less that I can spend on the family, and the holidays we like. I’m very angry that this is happening after I saved for so long.”

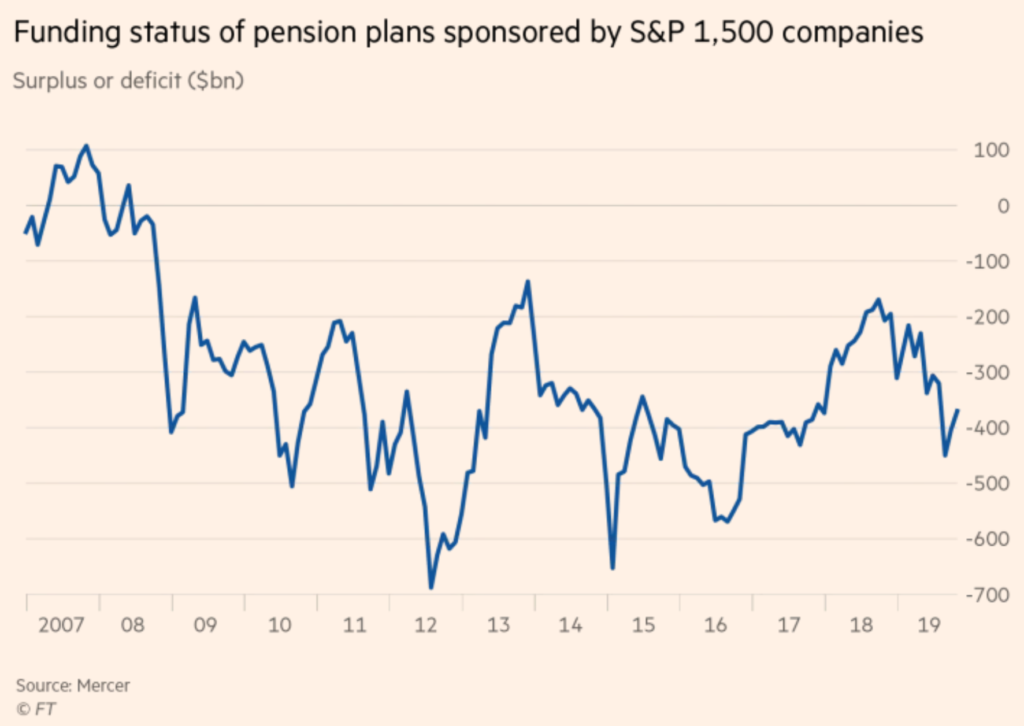

Mr Jansen is not alone in experiencing pension pain. Tens of millions more pensioners and savers around the world are facing the same retirement insecurity as Mr Jansen as plunging interest rates since the financial crisis wreak havoc on the funding of schemes. As average life expectancy increases, pensions have become a defining political issue in countries as diverse as Russia, Japan and Brazil.

General Electric, the US industrial conglomerate, recently announced that it is joining a growing list of companies that are ending guaranteed “final salary” style pension schemes, affecting around 20,000 of its employees. In the UK, tens of thousands of university academics are preparing to take strike action over steep rises in their pension contributions.

A common factor in this global pension upheaval has been suppressed bond yields.

Bonds have historically provided a simple match for the cash flows needed to be paid out to the members of retirement schemes such as Mr Jansen’s. But decades of declining bond yields have made it far harder for pension funds to buy an income for their members, pushing them more into equities and other riskier, untraded investments, such as real estate and private equity. […]

When Christopher Ailman studied for a degree in business economics at the University of California in the late 1970s, Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker was ratcheting up interest rates, sending bond yields spiralling higher. Soon after he graduated in 1980 the 10-year Treasury yield hit a record of nearly 16 per cent — and the concept of sub-zero yields seemed preposterous. “At school my textbooks said that there was no such thing as negative interest rates,” says Mr Ailman, now chief investment officer at Calstrs, the $238 billion Californian teachers’ pension plan. “But here we are.” […]

“In 20 years we may find ourselves with a real global crisis where we haven’t saved enough money for retirement,” says Calstrs’ Mr Ailman. “Returns can fluctuate, but longevity has been extended dramatically … We just have to explain to millennials that their parents might have to move back in with them.” [more]

‘Their house is on fire’: the pension crisis sweeping the world