Scientist has been counting California butterflies for 47 years and now sees them disappearing

By Deborah Netburn

12 November 2019

DONNER PASS, California (Los Angeles Times) – Art Shapiro stands on the edge of a Chevron gas station in the north-central Sierra, sipping a large Pepsi and scanning the landscape for butterflies.

So far he’s spotted six species — a loping Western tiger swallowtail, two fluttering California tortoiseshells, a copper-colored common checkered-skipper, a powdery echo blue, a rusty-looking Nelson’s hairstreak and a brown Propertius duskywing.

And that was while waiting for his ride to finish up in the restroom.

Shapiro jots the names of each species on a white note card, then tucks it into his T-shirt pocket stuffed with three pens, one Sharpie, a glasses case and newspaper clippings.

It’s not a bad showing for a gas station at 7,000 feet, he says, climbing back into the car. Last year was abysmal for butterflies in California. For the first time in his life, he didn’t see one single monarch caterpillar all summer long. This casual count at the rest stop indicates that 2019 will be better. But Shapiro isn’t celebrating yet.

One does not rejoice when one’s system is going away.

Art Shapiro, professor of evolution and ecology at UC Davis, on the decline of California butterflies

“Short-term fluctuations may or may not contain messages about longer-term trends,” he says. And the long-term trends are clear: In California, the butterflies are disappearing.

Shapiro, 73, is a professor of evolution and ecology at UC Davis and a collector of many things: quotes, books, names and stories. Particular interests include Argentinian politics, hermetic texts, meteorology and cheap beer. His specialty, however, is butterflies.

For nearly half a century he has meticulously tracked butterfly populations at 10 sites in north-central California, visiting each location every two weeks as long as the weather permits.

In that time he has single-handedly created the longest-running butterfly monitoring project in North America.

“It was originally designed as a five-year project, but the data were too good to stop collecting them,” he says. “And here I am, 47 years later.” […]

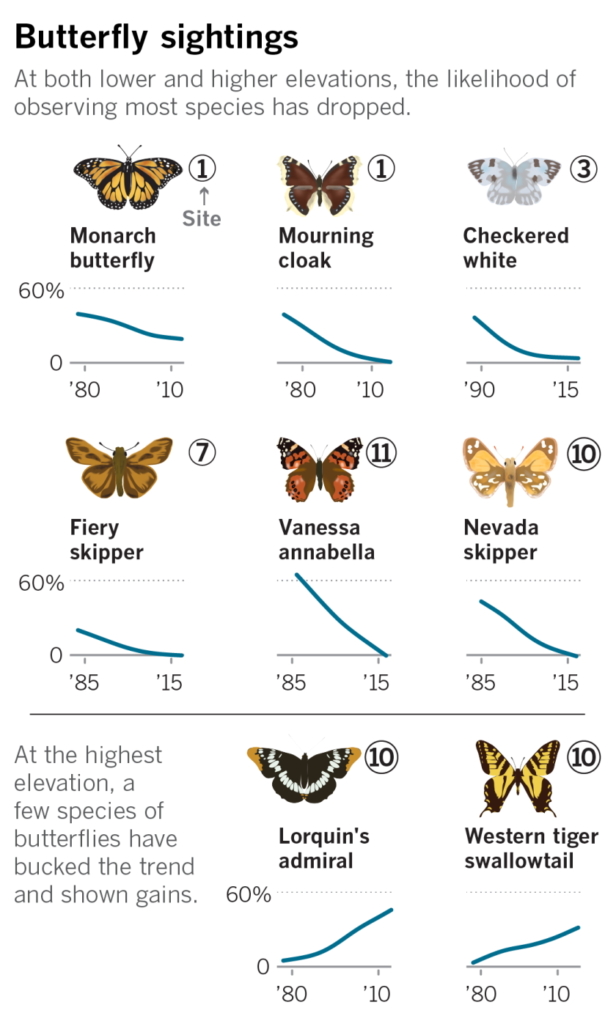

Shapiro’s monitoring study was designed to focus on fluctuations on very short timescales — what scientists call noise. But as he kept monitoring the same sites decade after decade, a disturbing long-term trend emerged in his data.

Without a doubt, the overall abundance of butterflies was declining.

He didn’t notice it at first. Insect populations are volatile, plummeting in years when weather conditions are unfavorable and, because they can reproduce so quickly, rising when conditions are just right.

But in 1999, 27 years after Shapiro started monitoring his sites, something strange happened: the populations of 17 species of butterflies at his low-elevation sites tumbled all at once.

“That got my attention,” he says. “We had never had so many species go down at the same time before. And we began to look at long-term trends more carefully as a result.”

What he and his colleagues found is that if you eliminate the noise from his data, the number of butterflies had decreased significantly at these sites from when he first started his project.

In recent years it has gotten much worse. Forister, who does much of the statistical analysis of Shapiro’s data, said that back in the 1970s, Shapiro would regularly see 30 species at some of his sites. Today he is more likely to find 20.

As a scientist, Shapiro knew this catastrophic count provided a valuable data point. The abysmal numbers could help other researchers understand how to make sense of future plunges in butterfly populations and perhaps help them pinpoint the culprit. But as a person who has spent his whole life among butterflies, he could not help but feel morose.

“One does not rejoice when one’s system is going away,” he says.

He told friends and colleagues that he felt like a physician who had known a patient for the patient’s entire life. Now the patient was obviously dying and he had no idea why.

Scientists who study butterfly populations blame a suite of factors for their decline, including loss of open spaces, changing agricultural practices and growing use of pesticides on farms and in home gardens. Statistical analysis also suggests that climate change has had an impact as well.

Shapiro’s educated hunch is that a group of pesticides known as neonicotinoids has played a significant role in the waning of populations, but he can’t be sure.

“The 1998-1999 season corresponded to widespread neonic use,” he says. “But we only have the correlation. We can’t prove it.” [more]

Meet the scientist who’s been counting California butterflies for 47 years and has no plans to stop