Deadly virus spreads among marine mammals as Arctic sea ice melts – Scientists fear the virus, once found only in European waters, could spread to the U.S. West Coast

By Sarah Gibbens

7 November 2019

(National Geographic) – When sea otters in Alaska were diagnosed with phocine distemper virus (PDV) in 2004, scientists were confused. The pathogen in the Morbillivirus genus that contains viruses like measles had then only been found in Europe and on the eastern coast of North America.

“We didn’t understand how a virus from the Atlantic ended up in these sea otters. It’s not a species that ranges widely,” says Tracey Goldstein, a scientist at the University of California Davis who investigates how pathogens move through marine ecosystems.

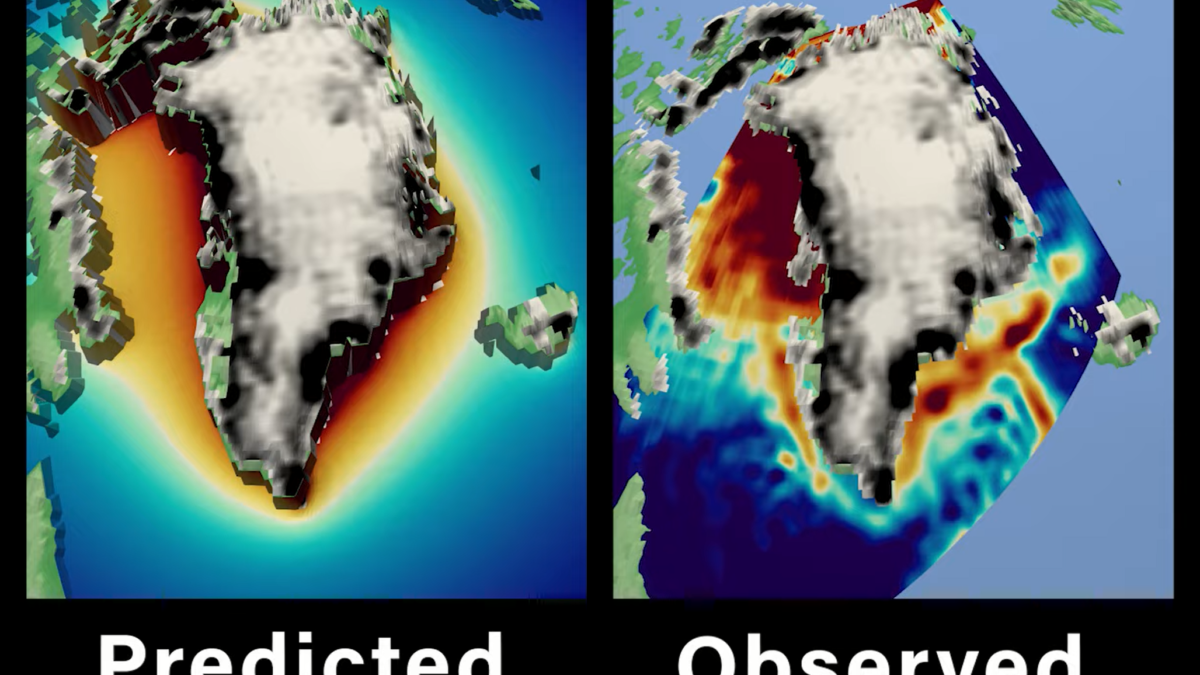

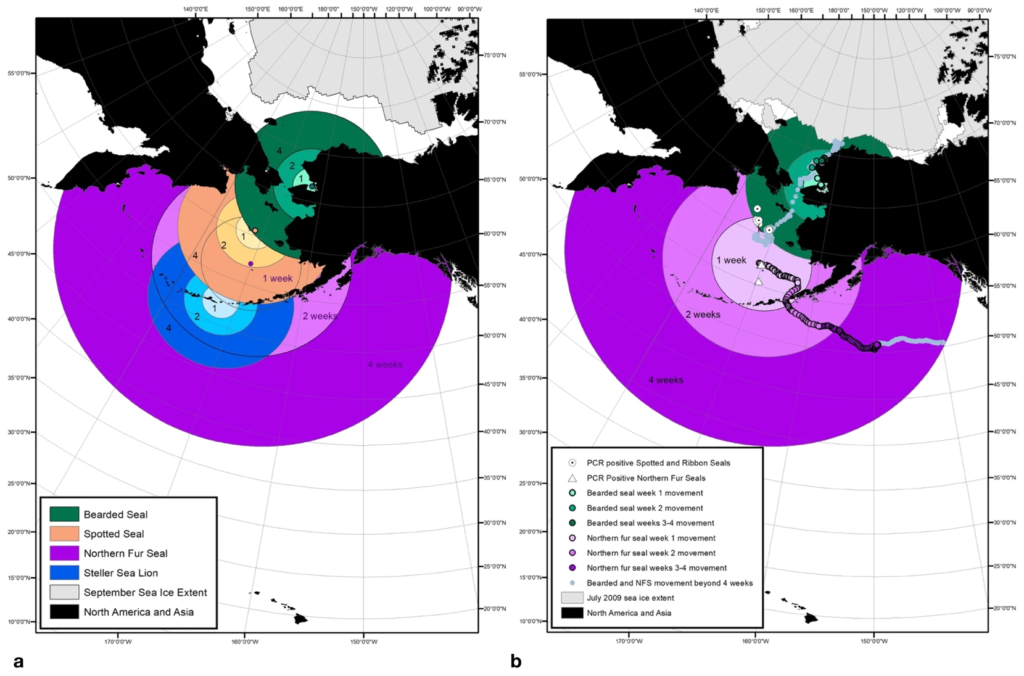

Using 15 years of data from 2001 to 2016, Goldstein and her research team were able to see upticks in PDV that corresponded with declines in Arctic sea ice. This new range for the otters likely allowed infected animals to move west, into new territories where the virus had not appeared before. The results of the study, published today in the journal Scientific Reports, shows how climate change may be opening up new pathways for disease to spread.

Phocine distemper virus was first detected in 1988 in northern Europe, where an estimated 18,000 seals died, most of them harbor seals. A similar outbreak occurred in 2002. It’s unclear where PDV originated. Some research has suggested it originated in the Arctic, but variations of distemper are found in dozens of animals. Local vets regularly vaccinate pet dogs against the canine version. […]

The first major outbreak of PDV along the U.S. East Coast occurred in 2006. Over the past year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has been logging what they describe as abnormally high numbers of dead seals from Maine to Virginia. Test results have shown PDV to be the primary culprit.

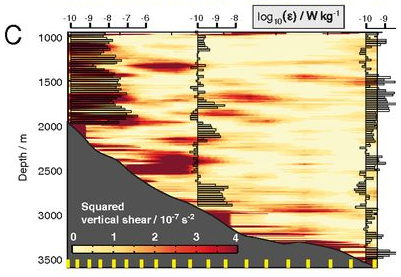

To construct when and where PDV spread from northern Europe to the northern Pacific just off the coast of Alaska, Goldstein and her team searched studies and records of biological samples taken from 2,530 live and 165 dead seals of species that spend at least part of their years on Arctic ice. They then looked at data showing the reach of sea ice at a given time of year, called Arctic ice extent. In years when sea ice extent was low, the following years showed an uptick in PDV. [more]

Deadly virus spreads among marine mammals as Arctic ice melts

Viral emergence in marine mammals in the North Pacific may be linked to Arctic sea ice reduction

ABSTRACT: Climate change-driven alterations in Arctic environments can influence habitat availability, species distributions and interactions, and the breeding, foraging, and health of marine mammals. Phocine distemper virus (PDV), which has caused extensive mortality in Atlantic seals, was confirmed in sea otters in the North Pacific Ocean in 2004, raising the question of whether reductions in sea ice could increase contact between Arctic and sub-Arctic marine mammals and lead to viral transmission across the Arctic Ocean. Using data on PDV exposure and infection and animal movement in sympatric seal, sea lion, and sea otter species sampled in the North Pacific Ocean from 2001–2016, we investigated the timing of PDV introduction, risk factors associated with PDV emergence, and patterns of transmission following introduction. We identified widespread exposure to and infection with PDV across the North Pacific Ocean beginning in 2003 with a second peak of PDV exposure and infection in 2009; viral transmission across sympatric marine mammal species; and association of PDV exposure and infection with reductions in Arctic sea ice extent. Peaks of PDV exposure and infection following 2003 may reflect additional viral introductions among the diverse marine mammals in the North Pacific Ocean linked to change in Arctic sea ice extent.

Viral emergence in marine mammals in the North Pacific may be linked to Arctic sea ice reduction