Greenhouse gas concentrations in atmosphere reached yet another high in 2018

GENEVA, 25 November 2019 (WMO) – Levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have reached another new record high, according to the World Meteorological Organization. This continuing long-term trend means that future generations will be confronted with increasingly severe impacts of climate change, including rising temperatures, more extreme weather, water stress, sea level rise and disruption to marine and land ecosystems.

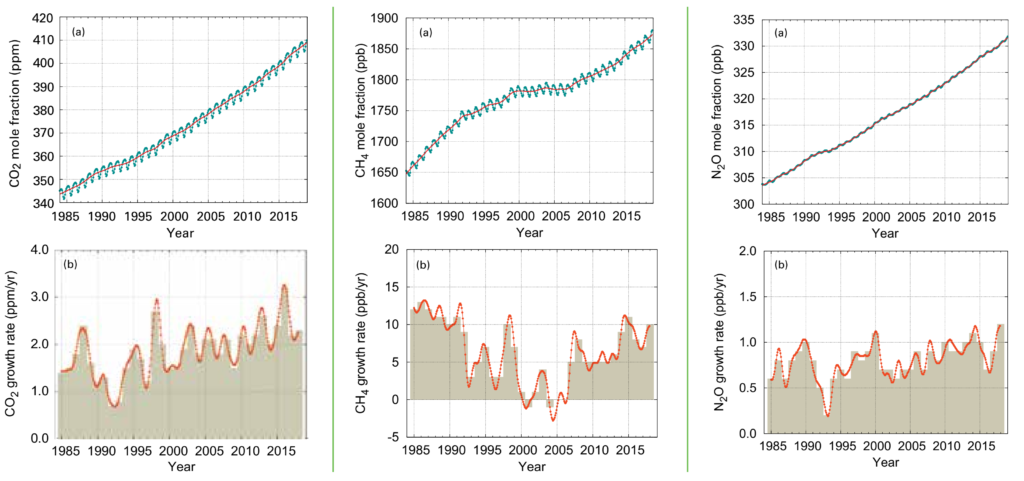

The WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin showed that globally averaged concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) reached 407.8 parts per million in 2018, up from 405.5 parts per million (ppm) in 2017.

The increase in CO2 from 2017 to 2018 was very close to that observed from 2016 to 2017 and just above the average over the last decade. Global levels of CO2 crossed the symbolic and significant 400 parts per million benchmark in 2015.

CO2 remains in the atmosphere for centuries and in the oceans for even longer.

Concentrations of methane and nitrous oxide also surged by higher amounts than during the past decade, according to observations from the Global Atmosphere Watch network which includes stations in the remote Arctic, mountain areas and tropical islands.

Since 1990, there has been a 43% increase in total radiative forcing – the warming effect on the climate – by long-lived greenhouse gases. CO2 accounts for about 80% of this, according to figures from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration quoted in the WMO Bulletin.

“There is no sign of a slowdown, let alone a decline, in greenhouse gases concentration in the atmosphere despite all the commitments under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change,» said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas. “We need to translate the commitments into action and increase the level of ambition for the sake of the future welfare of the mankind,” he said.

“It is worth recalling that the last time the Earth experienced a comparable concentration of CO2 was 3-5 million years ago. Back then, the temperature was 2-3°C warmer, sea level was 10-20 meters higher than now,” said Mr Taalas.

Emissions Gap

The WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin reports on atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. Emissions represent what goes into the atmosphere. Concentrations represent what remains in the atmosphere after the complex system of interactions between the atmosphere, biosphere, lithosphere, cryosphere and the oceans. About a quarter of the total emissions is absorbed by the oceans and another quarter by the biosphere.

Global emissions are not estimated to peak by 2030, let alone by 2020, if current climate policies and ambition levels of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are maintained. Preliminary findings from the Emissions Gap Report 2019 indicate that greenhouse gas emissions continued to rise in 2018, according to an advanced chapter of the Emissions Gap Report released as part of a United in Science synthesis for the UN Secretary-General’s Climate Action Summit in September.

The United in Science report, which brought together major partner organizations in the domain of global climate change research, underlined the glaring – and growing – gap between agreed targets to tackle global warming and the actual reality.

“The findings of WMO’s Greenhouse Gas Bulletin and UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report point us in a clear direction – in this critical period, the world must deliver concrete, stepped-up action on emissions,” said Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). “We face a stark choice: set in motion the radical transformations we need now, or face the consequences of a planet radically altered by climate change.”

A separate and complementary Emissions Gap Report by UN Environment will be released on 26 November 2019. Now in its tenths year, the Emissions Gap report assesses the latest scientific studies on current and estimated future greenhouse gas emissions; they compare these with the emission levels permissible for the world to progress on a least-cost pathway to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. This difference between “where we are likely to be and where we need to be” is known as the emissions gap.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres said the Summit had delivered “a boost in momentum, cooperation and ambition. But we have a long way to go.”

This will now be taken forward by the UN Climate Change Conference, which will be held from 2 to15 December in Madrid, Spain, under the presidency of Chile.

Key Findings of the Greenhouse Gas Bulletin

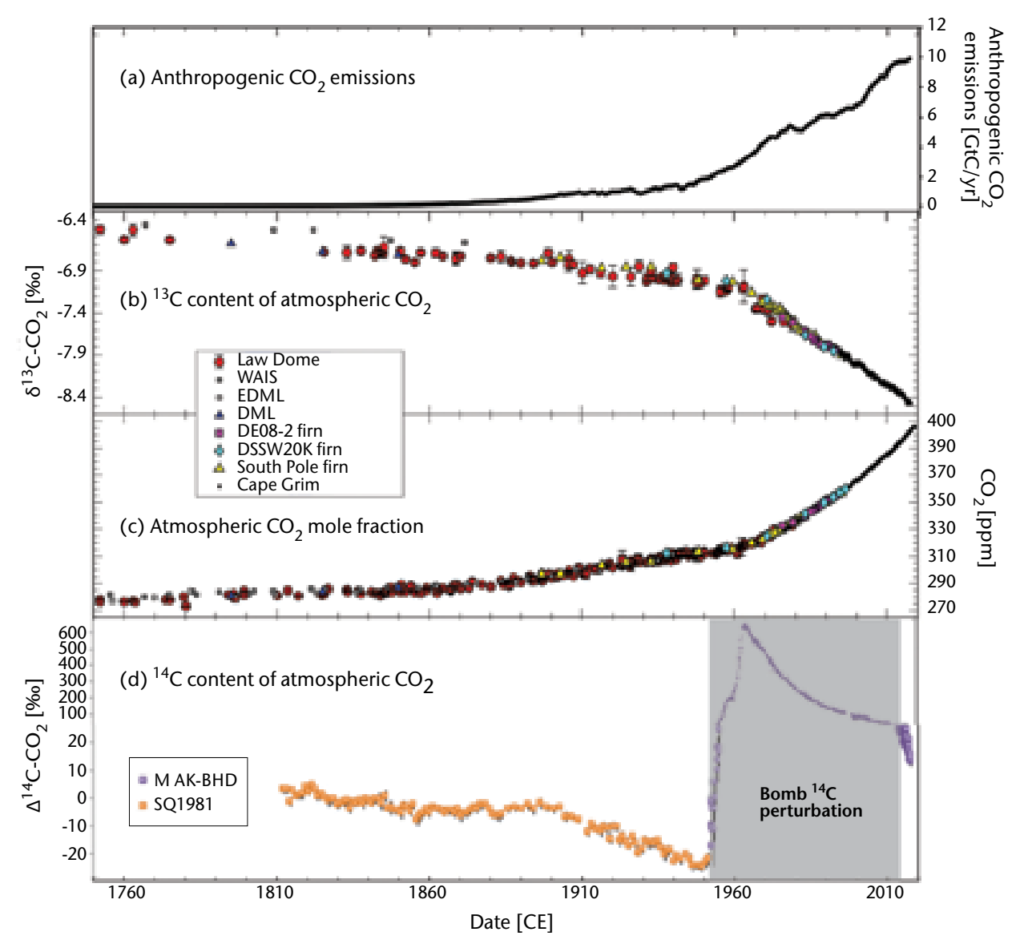

The bulletin includes a focus on how isotopes confirm the dominant role of fossil fuel combustion in the increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

There are multiple indications that the increase in the atmospheric levels of CO2 are related to fossil fuel combustion. Fossil fuels were formed from plant material millions of years ago and do not contain radiocarbon. Thus, burning it will add to the atmosphere radiocarbon-free CO2, increasing CO2 levels and decreasing its radiocarbon content. And this is exactly what is demonstrated by the measurements.

Carbon Dioxide

Carbon dioxide is the main long-lived greenhouse gas in the atmosphere related to human activities. Its concentration reached new highs in 2018 of 407.8 ppm, or 147% of pre-industrial level in 1750.

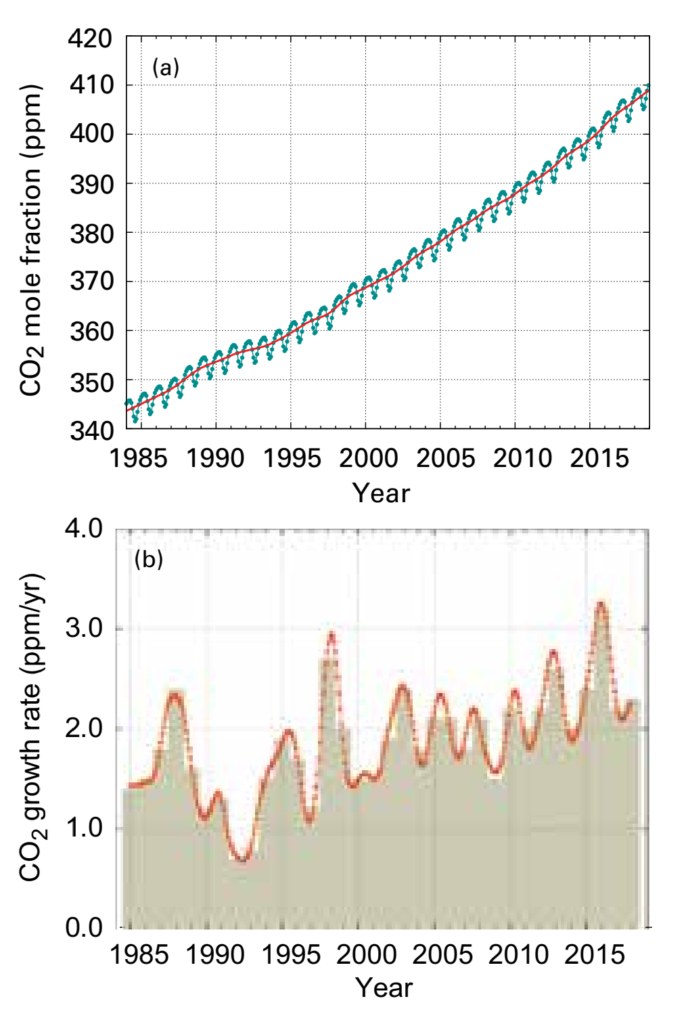

The increase in CO2 from 2017 to 2018 was above the average growth rate over the last decade. The growth rate of CO2 averaged over three consecutive decades (1985–1995, 1995–2005 and 2005–2015) increased from 1.42 ppm/yr to 1.86 ppm/yr and to 2.06 ppm/yr with the highest annual growth rates observed during El Niño events.

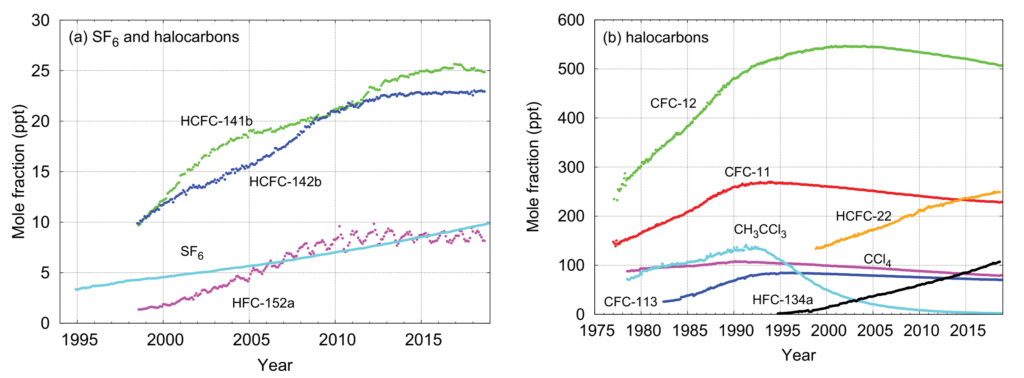

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Annual Greenhouse Gas Index shows that from 1990 to 2018 radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases (LLGHGs) increased by 43%, with CO2 accounting for about 80% of this increase

Methane

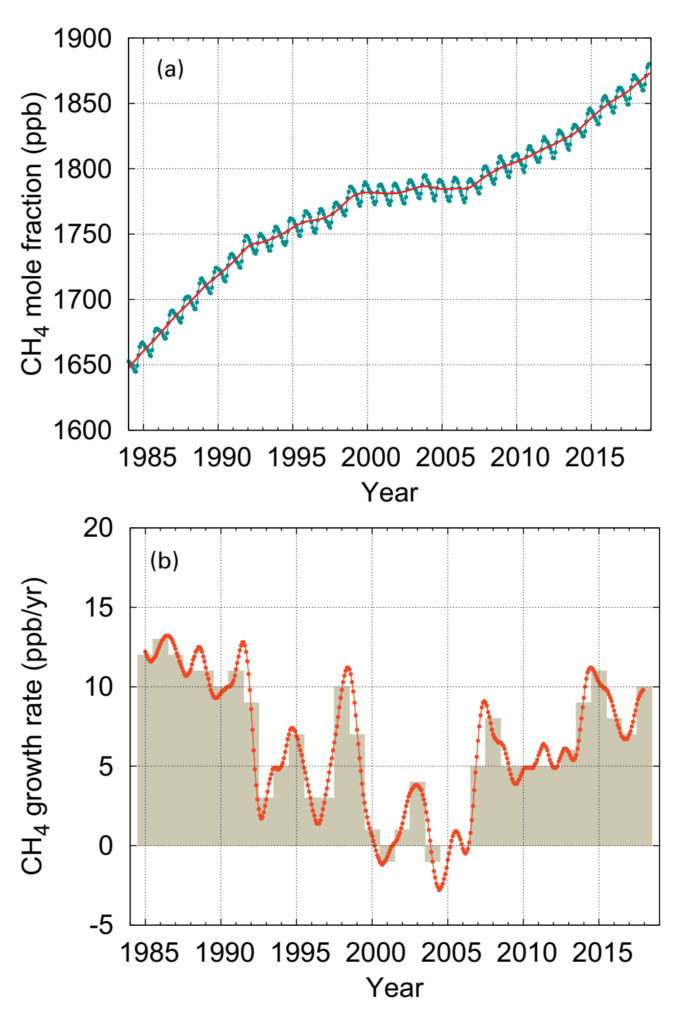

Methane (CH4) is the second most important long-lived greenhouse gas and contributes about 17% of radiative forcing. Approximately 40% of methane is emitted into the atmosphere by natural sources (e.g., wetlands and termites), and about 60% comes from human activities like cattle breeding, rice agriculture, fossil fuel exploitation, landfills and biomass burning.

Atmospheric methane reached a new high of about 1869 parts per billion (ppb) in 2018 and is now 259% of the pre-industrial level. For CH4, the increase from 2017 to 2018 was higher than both that observed from 2016 to 2017 and the average over the last decade.

Nitrous Oxide

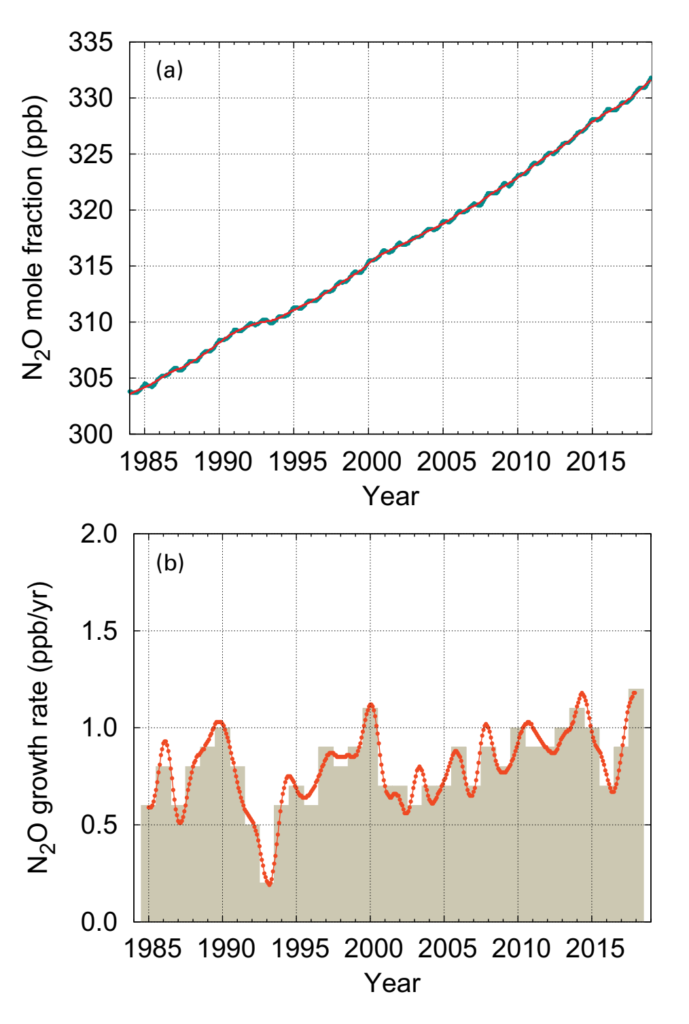

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is emitted into the atmosphere from both natural (about 60%) and anthropogenic sources (approximately 40%), including oceans, soil, biomass burning, fertilizer use, and various industrial processes.

Its atmospheric concentration in 2018 was 331.1 parts per billion. This is 123% of pre-industrial levels. The increase from 2017 to 2018 was also higher than that observed from 2016 to 2017 and the average growth rate over the past 10 years.

Nitrous oxide also plays an important role in the destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer which protects us from the harmful ultraviolet rays of the sun. It accounts for about 6% of radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases. [more]

Greenhouse gas concentrations in atmosphere reach yet another high