“Climategate” 10 years on: what lessons have we learned? “British climate science was subjected to huge scrutiny by the world’s best journalists and it stood up to the test”

By Robin McKie

9 November 2019

(The Guardian) – The email that appeared on Phil Jones’s computer screen in November 2009 was succinct. “Just a quick note to encourage you to shoot yourself in the head,” it said. “Don’t waste any more time. Do it today. It is truly the greatest contribution to mankind that you will ever make.”

Nor was it very different from the other emails that were arriving in Jones’s inbox. Others described the climate scientist as the scum of the earth. Some authors promised to kill him themselves. Most of the messages were riddled with obscenities. All made troubling reading.

As to the cause of this outpouring of hatred, that was straightforward. Jones headed the University of East Anglia’s Climate Research Unit, from which a tranche of emails had just been hacked and made public. These, it was claimed, showed that he and fellow researchers were faking the evidence that suggested our planet was heating up dangerously.

The affair was dubbed “Climategate” by those who deny the existence of global warming and it remains one of modern society’s most troubling affairs. Many observers believe it helped delay measures that might have slowed climate change and given humanity more time to cut atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, its key cause.

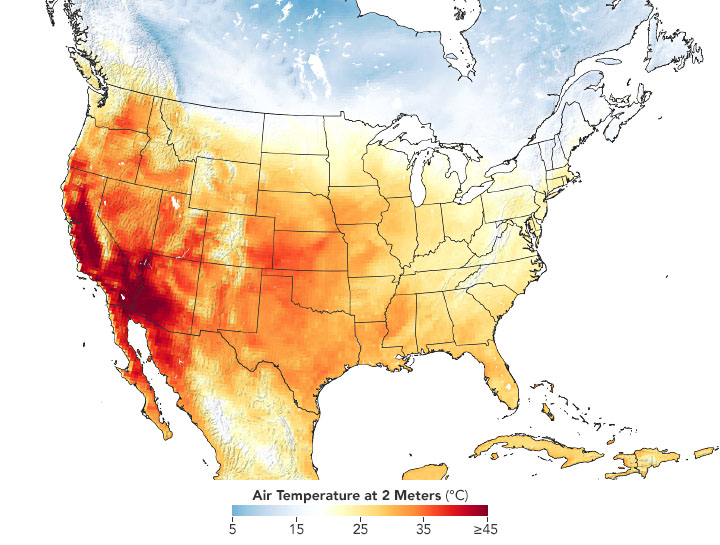

Climategate marks its 10th anniversary this month – an opportune moment to reflect on just how serious was its impact on society, and to look at the effect it had on those who were trying to stop Earth from being ravaged by rising seas, spreading deserts, disappearing coral reefs and suffocating heat.

At the time, climate-change deniers were desperate to find ways to undermine the idea that global warming was real, and as Jones’s unit had provided key data that supported this notion – by showing how land temperatures on Earth had been rising sharply in recent decades – his work was considered fair game. So they responded gleefully by ransacking his hacked emails for signs he may have been fiddling results and asserted, in blogs, they had found telltale signs.

These claims were then picked up by media outlets hostile to global warming. “Scientist in climate cover-up told to quit” ran one headline. “Scientists broke law by hiding climate data”, claimed another.

Jones was vilified. “Within a day or two reporters were outside my house, knocking on my neighbours’ doors, digging for dirt,” he recalls. “I got hundreds of abusive and threatening emails. I knew the accusations were nonsense. But as someone used to being in control I buckled at the loss of it. My health deteriorated. I found it difficult to sleep and eat. I was under intense, spiralling pressure and felt I was falling to pieces. Looking back I suppose I was having some kind of a nervous breakdown.” […]

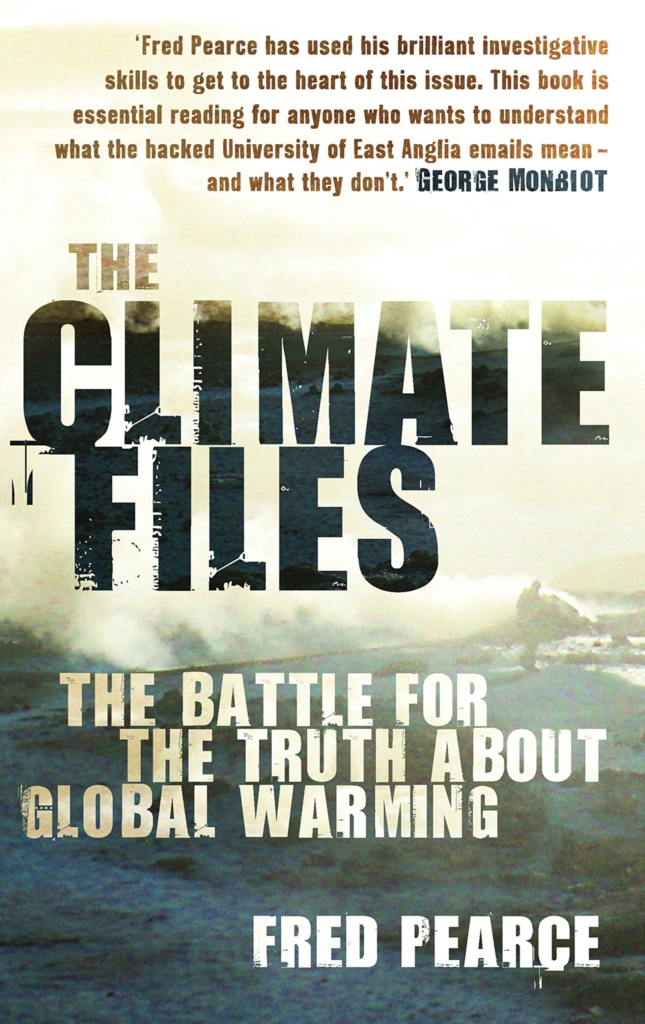

Subsequent investigations by journalists showed these claims were unsupportable, however. Guardian writer Fred Pearce studied the leaked emails and produced a book, The Climate Files, from his research. “Have the Climategate revelations undermined the case that we are experiencing made-made climate change? Absolutely not,” says Pearce. “Nothing uncovered in the emails destroys the argument that humans are warming the planet.”

Pearce was writing for the eco-friendly Guardian, but his views were supported by many others, such as Mike Hanlon, former science editor of the Daily Mail. “Scratch and sniff as we did, there was no smoking gun, no line that would show that there had been a conspiracy to fabricate a great untruth,” he said later. Thus, from the Guardian to the Daily Mail, the notion that Climategate represented “the worst scientific scandal of a generation” – as one UK newspaper had claimed – was found in the end to be unsupportable.

This point is emphasised by Fiona Fox, head of the UK’s Science Media Centre. “British climate science was subjected to huge scrutiny by the world’s best journalists and it stood up to the test. If you look at where we are now in terms of public trust in climate science, it’s hard to sustain the argument that Climategate was fatally damaging to the field.

“Climategate also tells us that front page rows about science are an opportunity as well as a threat and the scientists who stood up in that febrile environment and soundly defended science also did a great job. We need to remember that.” [more]