Hurricane Michael survivors hanging on one year later – Thousands of Panhandle residents still live in tents, trailers, and hotel rooms – “Collectively we’ve forgotten them”

By Nada Hassanein

12 October 2019

SNEADS, Florida (Tallahassee Democrat) – Rodney and Tonya Hewett remember gazing outside the window of their farmhouse during Hurricane Michael. They saw their pool fence flying in the forceful winds, the wooden poles like swords. A deer that tried to run for safety went airborne.

The Hewetts have been farming on the property tucked off River Road for the past three decades. But when Michael tore through their rural town, it stripped acres of cotton and peanuts. Unpicked, soggy cotton bolls lay scattered, bogged into mud.

A year’s worth of income was gone.

“We had a bumper crop — we had the best crop we had in years,” Rodney, 53, said.

A $70,000 barn filled with cotton-picking equipment and tools was destroyed. A year later, the barn is still in shambles, and the couple is slowly sifting through to find pieces that still work.

A year after the storm, it’s a familiar story for many farmers in the path of Michael’s fury in the close-knit country town of about 1,800 people 50 miles northwest of Tallahassee, where streets have names like “Hoecake Road” and “Pea Ridge Road.”

Homes throughout the Jackson County community are abandoned, windows still boarded up, trailers demolished. Surrounding the bridge over the Apalachicola River leading west into the town, patches of once-lush forests are desolate, save for leftover shreds of timber.

“It’s so sad because, some of these people, it’s their savings, it’s their investment — it’s their heritage,” Sneads City Manager Lynda Bell, 62, said of the timber. “I don’t know that there was an area that wasn’t affected — everyone was affected.” […]

The Hewetts sell their cotton and peanuts in southern Georgia and Alabama. Rodney estimates about $350,000 in total damages. Insurance paid about a third, but the couple is still down roughly $150,000.

“Stress. Bills. Stress. Are we going to be able to do this? Yeah, I hope,” Tonya, 52, said. “Can we overcome it? Yeah, we can — with God, but, we’ll make it.”

When Dorian pounded the Bahamas, Tonya couldn’t help but cry for the battered islands.

“My heart bleeds for them people,” she said. “If it had came here, I was gone. I told Rodney, I would never live through another storm like that.”

“It is a big blow,” he said. “We have crop insurance and all that covers some, but it doesn’t nearly cover what we would have made.” [more]

‘Stress. Bills. Stress’: Farming couple in Sneads lost a year’s income after Hurricane Michael

By Jeffrey Schweers

4 October 2019

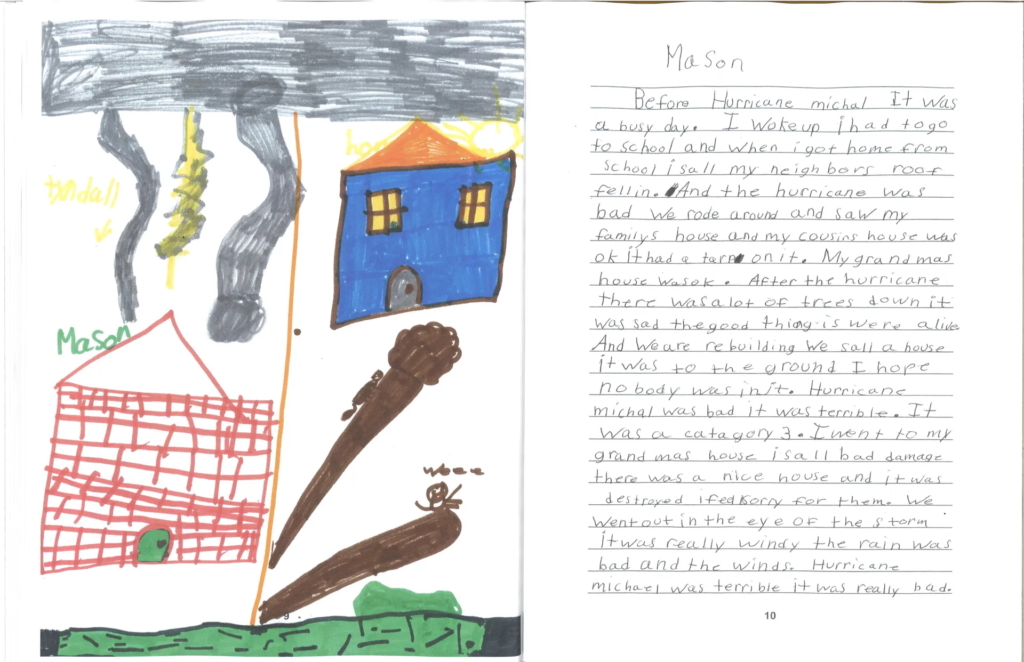

PANAMA CITY, Florida (Tallahassee Democrat) – A year after Hurricane Michael struck North Florida, thousands of Panhandle residents still live in tents, trailers and hotel rooms, homeowners continue to fight their insurance companies over repairs, and children attend school in portable classrooms, flinching every time it thunders.

Michael struck Mexico Beach with 155 mph winds and a 15-foot storm surge that swamped beachfront houses and businesses, flattening the gulf resort town. It plowed through the center of the sparsely populated rural Panhandle region of about 330,000 residents, cutting a 30- to 40-mile-wide swath between Panama City and Port St. Joe all the way to Georgia, pulverizing small towns and chewing up billions of dollars in timber, cotton and peanuts.

It caused $25 billion in damage, including $3 billion in agricultural losses and $16.5 billion in property losses in Florida alone. Just about every standing structure was damaged to some degree, and affordable housing, already a problem before the storm, became nonexistent.

Folks on Florida’s Forgotten Coast fear the media and the nation have moved on from Michael. Worse, they feel abandoned by a government they came to count on in times of need following a major natural disaster.

Even President Trump, who was elected with the help of this heavily red-leaning region, said he was not sure he had ever heard of a Category 5 hurricane when Dorian was bearing down on the Bahamas, 11 months after Michael had wiped Mexico Beach off the map.

“Collectively we’ve forgotten them,” said Florida Sen. Bill Montford, a former Leon County high school principal and school superintendent who grew up in Blountstown. “Our memory is shorter than the impact of that storm, and that’s what we’re facing. For us it’s very personal. When you are living in a tent, when you are hungry, a month is a very long time. After eight months people start to lose their patience.”

The aid money isn’t flowing

As Montford frequently likes to remind folks at town hall meetings and legislative committee hearings, eight months is how long it took for Congress to approve a $19 billion emergency disaster relief aid package for several national disasters since 2017, including Michael.

It’s intended to supplement the $1.9 billion in funding already obligated by FEMA and other federal agencies for people in the 12 counties clobbered by Michael – a fraction of the total $16.5 billion in both insured and uninsured property losses.

It isn’t as if FEMA officials are standing on street corners handing out checks and money orders. Governments have to spend money to get money. People have to apply for grants and loans, and often as not, don’t qualify or get rejected.

“There’s a lot of needs in this county,” Calhoun County Commission Chairman Gene Bailey said at a town hall meeting held in the county courthouse basement.

He appreciates what help the county has received, especially for debris removal. “But I get tired of hearing people ask what is the board doing with the $500,000 or that $2 million when we haven’t gotten it yet. The reality is we’ve only received $125,000. We need that money and we need it bad.”

Officials from Panama City to Marianna echo Bailey’s complaints.

Small towns don’t have the money to pay for debris removal and essential basic repairs up front, while others said they don’t expect to be reimbursed for years.

What money they have seen is stabilization money from FEMA, and not the recovery money approved by Congress in July, said Leon County Commissioner Kristin Dozier.

“The recovery dollars haven’t even begun yet,” she said.

Bay County Schools racked up $400 million in damage and lost materials and a $100 million insurance policy, officials there said. They need to find $300 million. They scrounged $40 million together to start paying for the most basic repairs, and spread polymer material over most of its roofs as a stopgap measure until it gets more money. […]

Apocalyptic scenes frozen in time

There is still an apocalyptic feel to some hard-hit locations that appear trapped in time. Blue tarps are rotting over unrepaired houses. Trees are still resting on rooftops. Church steeples are still missing. Gas station canopies are twisted metal modern art sculpted by the wind. Plywood boards cover the great plate glass picture windows of downtown stores. Entire shopping malls are deserted.

Blountstown’s historic courthouse still has a blue tarp on its roof, the city’s police headquarters still abandoned.

Crumbled walls and vacant lots are all that remain of office buildings in Marianna, its county buildings still waiting for repairs.

The First Baptist Church in Port St. Joe still has exposed roof beams, never to be repaired. Downtown shops have yet to clear the debris out of their interiors. [more]

‘Collectively we’ve forgotten them’: Hurricane Michael survivors hanging on one year later