Imelda rainfall is now 7 times more likely than 30 years ago – Climate change is making flooding more frequent in southeast Texas

By Jeff Berardelli

22 September 2019

(CBS News) – Over 36 inches of rain fell in just 36 hours in parts of coastal Texas this week. Astronomical rain rates of 6 inches per hour were observed generating the equivalent of a month’s worth of rain in 60 minutes.

Imelda’s immense rainfall is both amazing and also desensitizing – very rare, historic rainfall has now fallen along the western Gulf Coast a few times in as many years. It’s becoming a lot more common because of climate change.

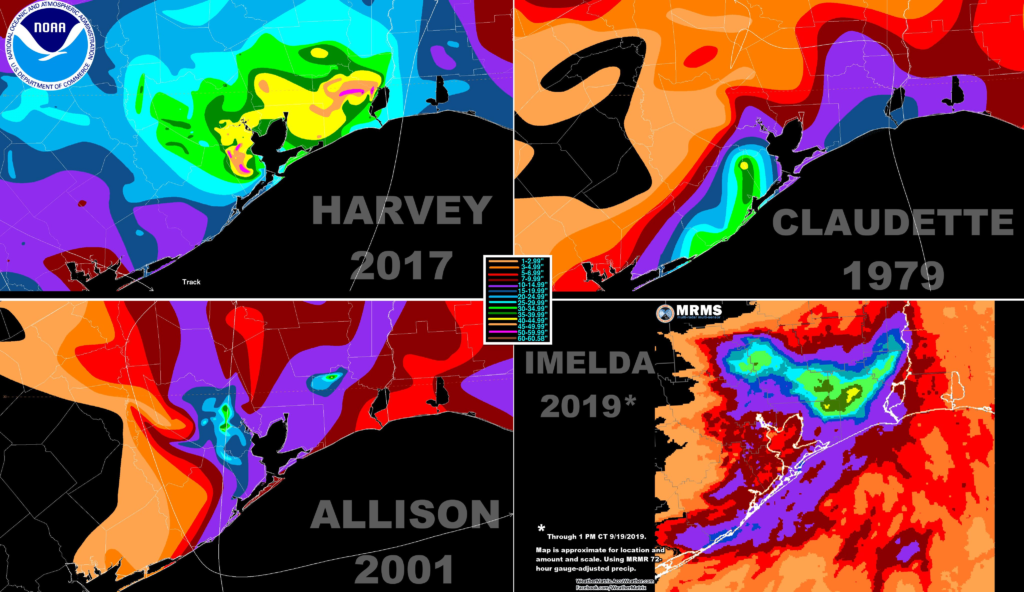

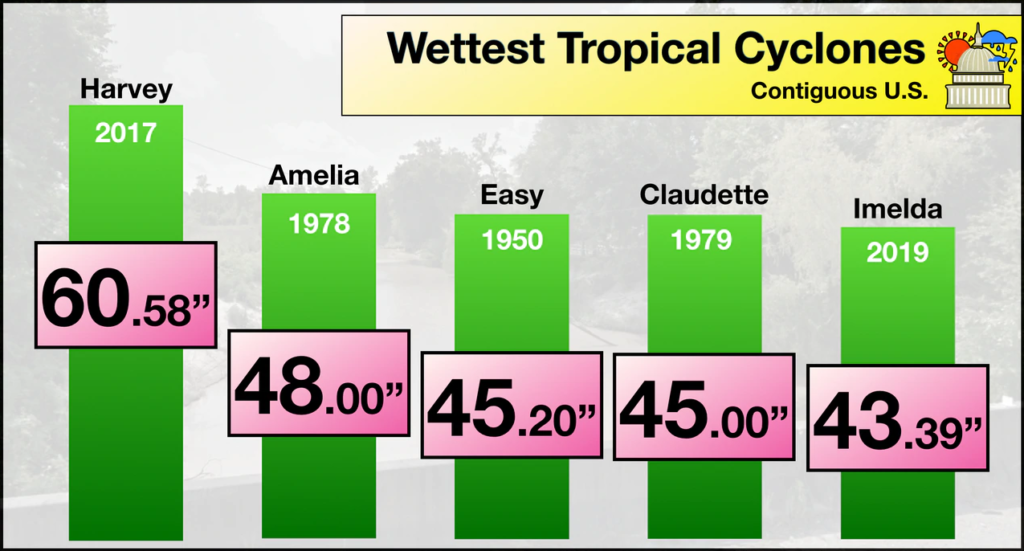

According to the National Weather Service in Lake Charles, Louisiana, “this event is unofficially the fifth wettest tropical cyclone in the continental U.S. history.”

Noted MIT Atmospheric Science Professor Dr. Kerry Emanuel analyzed the likelihood of historic rain events like Hurricane Harvey in Texas following the 2017 storm. He called Harvey’s rainfall in Houston “biblical” in that it is only likely to occur once since the Old Testament was written.

Using a very low-end estimate of 20 inches for Harvey’s rainfall in the city of Houston, Emanuel found that “the probability of rainfall larger than this magnitude is around once in 2,000 years” in the climate of the 1980s and 1990s.

But given the recent rapid changes in climate due to heat trapping greenhouse gases, the probability of event like Harvey happening in 2017 increased markedly to 1 in 325 years.

CBS News reached out to Emanuel about the probability of an event the magnitude of Imelda occurring along the Texas East Coast. Emanuel estimates “that for the region affected, this would have been about a once in 700-year event in the late 20th century but has increased to about a 1 in 100-year event today.”

What that translates to is a 7-fold increase in the likelihood of an event like Imelda happening in just a few decades.

The science on this is rather simple: The atmosphere has warmed around 2 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1800s. For every 2 degrees of temperature rise, the atmosphere holds 8% more moisture and thus squeezes out more heavy rain. […]

The last point is the slow movement of storms like Harvey and Imelda. While storms sometimes travel slowly and stall for natural reasons, a 2018 study by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientist James Kossin shows that the forward motion, especially of tropical systems making landfall, has slowed by 16% in the Atlantic basin. As for the reasoning, Kossin cites evidence linking global warming to the weakening of the summertime tropical circulation. [more]

Imelda’s rainfall is now 7 times more likely than 30 years ago

Flooded again: Climate change is making flooding more frequent in southeast Texas

By Andrew Freedman and Jason Samenow

20 September 2019

(The Washington Post) – Tropical Storm Imelda enters the history books as one of the top five wettest tropical cyclones to ever strike the lower 48 states, with a maximum rainfall total of 43.39 inches. On Friday morning, flood waters are continuing to block roads, damage homes and cause gridlock in the Houston metro area and especially in the vicinity of Beaumont and Port Arthur, where new flood warnings were issued for additional rainfall of up to 4 inches.

That this storm comes just two years after Hurricane Harvey dumped an almost unimaginable 60.58 inches of rain, on the same general area is no accident. In addition, there have been other major rain events in Southeast Texas in the past 5 years that caused extensive disruptions and damage.

Recent studies show that slow-moving tropical cyclones in the U.S. are becoming more frequent, and increased ocean heat content is supercharging the rainfall potential of such storms, making them more formidable rain producers than they otherwise would be.

For example, a study published in the journal Earth’s Future in 2018 found that Hurricane Harvey’s gargantuan rainfall totals were directly related to record high ocean heat content in the western Gulf of Mexico. The oceans are absorbing the vast majority of extra heat from human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, with temperatures increasing in the process.

This is translating into additional water vapor, which storms tap into as fuel and then wring out like a wet sponge. If their forward speed slows to a crawl, as Harvey and Imelda did as tropical depressions, they can produce rainfall totals measured in feet rather than inches. As Tropical Storm Imelda formed on top of the Texas coast, and then drew in moisture from Gulf waters that were between 1.8 and 3.6 degrees above average for this time of year.

The 2018 study found that the energy released into the atmosphere from Harvey’s rainfall was equivalent to the amount of energy removed from the ocean in the storm’s wake. In other words, the study found that the amount of heat stored in the ocean is directly related to how much rain a storm can produce.

“[R]ecord high ocean heat values not only increased the fuel available to sustain and intensify Harvey, but also increased its flooding rains on land,” the study said. “Harvey could not have produced so much rain without human-induced climate change.”

Two other studies found climate change increased Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall by between 20 to 35 percent.

In addition, many areas in the U.S. have seen increases in heavy precipitation events overall, including Texas, as laid out in the 2018 Fourth National Climate Assessment. [more]