Fracking prompts global spike in atmospheric methane – “This recent increase in methane in massive”

By Blaine Friedlander

14 August 2019

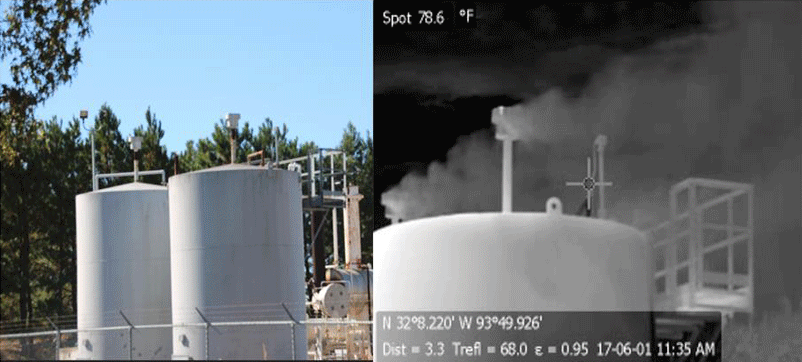

(Cornell Chronicle) – As methane concentrations increase in the Earth’s atmosphere, chemical fingerprints point to a probable source: shale oil and gas, according to new Cornell research published 14 August 2019 in Biogeosciences, a journal of the European Geosciences Union.

The research suggests that this methane has less carbon-13 relative to carbon-12 (denoting the weight of the carbon atom at the center of the methane molecule) than does methane from conventional natural gas and other fossil fuels such as coal.

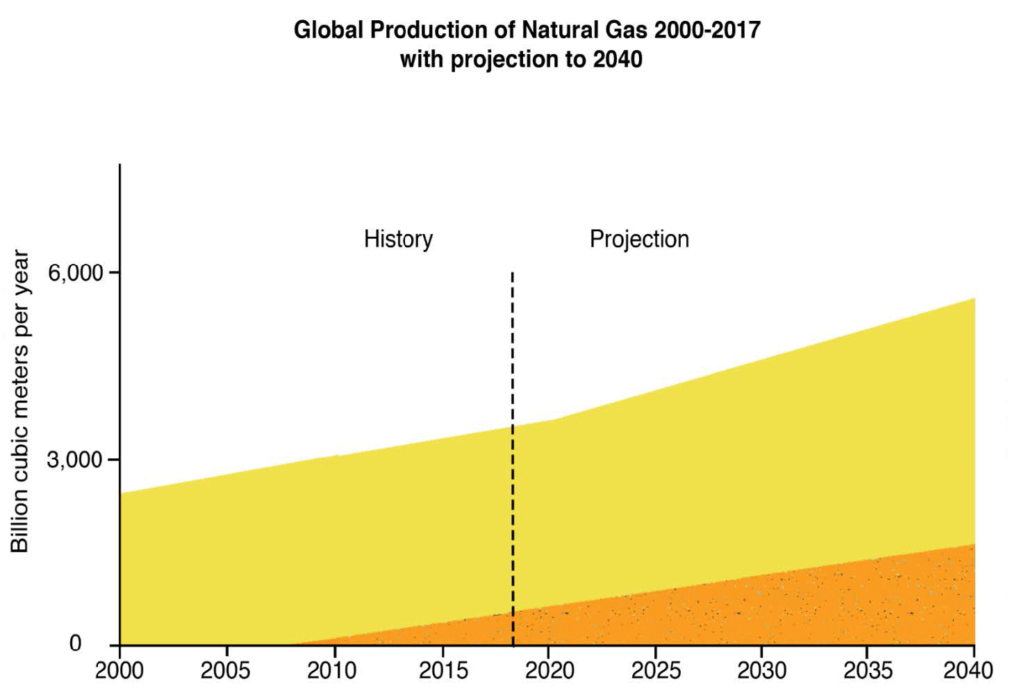

This carbon-13 signature means that since the use of high-volume hydraulic fracturing – commonly called fracking – shale gas has increased in its share of global natural gas production and has released more methane into the atmosphere, according to the paper’s author, Robert Howarth, the David R. Atkinson Professor of Ecology and Environmental Biology at Cornell.

About two-thirds of all new gas production over the last decade has been shale gas produced in the United States and Canada, he said.

While atmospheric methane concentrations have been rising since 2008, the carbon composition of the methane has also changed. Methane from biological sources such as cows and wetlands have a low carbon-13 content – compared to methane from most fossil fuels. Previous studies erroneously concluded that biological sources are the cause of the rising methane, Howarth said.

Carbon dioxide and methane are critical greenhouse gases, but they behave quite differently in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide emitted today will influence the climate for centuries to come, as the climate responds slowly to decreasing amounts of the gas.

Unlike its slow response to carbon dioxide, the atmosphere responds quickly to changes in methane emissions.

“Reducing methane now can provide an instant way to slow global warming and meet the United Nations’ target of keeping the planet well below a 2-degree Celsius average rise,” Howarth said, referring to the 2015 Paris Agreement that boosts the global response to climate change threats.

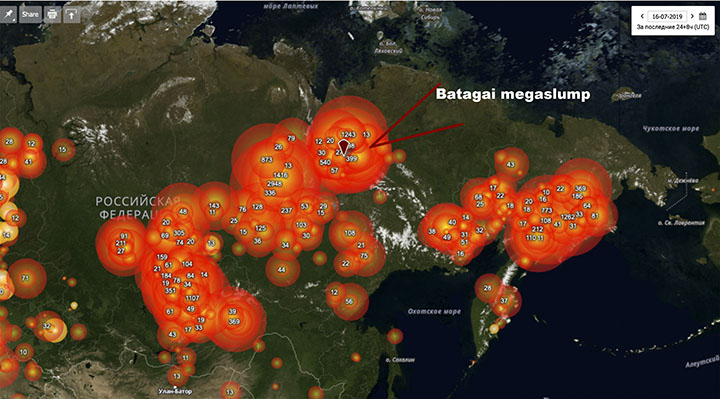

Atmospheric methane levels had previously risen during the last two decades of the 20th century but leveled in the first decade of 21st century. Then, atmospheric methane levels increased dramatically from 2008-14, from about 570 teragrams (570 billion tons) annually to about 595 teragrams, due to global human-caused methane emissions in the last 11 years.

“This recent increase in methane in massive,” Howarth said. “It’s globally significant. It’s contributed to some of the increase in global warming we’ve seen and shale gas is a major player.

“If we can stop pouring methane into the atmosphere, it will dissipate,” he said. “It goes away pretty quickly, compared to carbon dioxide. It’s the low-hanging fruit to slow global warming.”

This research was funded by the Park Foundation and the Atkinson Center.

Study: Fracking prompts global spike in atmospheric methane

Is shale gas a major driver of recent increase in global atmospheric methane?

ABSTRACT: Methane has been rising rapidly in the atmosphere over the past decade, contributing to global climate change. Unlike the late 20th century when the rise in atmospheric methane was accompanied by an enrichment in the heavier carbon stable isotope (13C) of methane, methane in recent years has become more depleted in 13C. This depletion has been widely interpreted as indicating a primarily biogenic source for the increased methane. Here we show that part of the change may instead be associated with emissions from shale-gas and shale-oil development. Previous studies have not explicitly considered shale gas, even though most of the increase in natural gas production globally over the past decade is from shale gas. The methane in shale gas is somewhat depleted in 13C relative to conventional natural gas. Correcting earlier analyses for this difference, we conclude that shale-gas production in North America over the past decade may have contributed more than half of all of the increased emissions from fossil fuels globally and approximately one-third of the total increased emissions from all sources globally over the past decade.