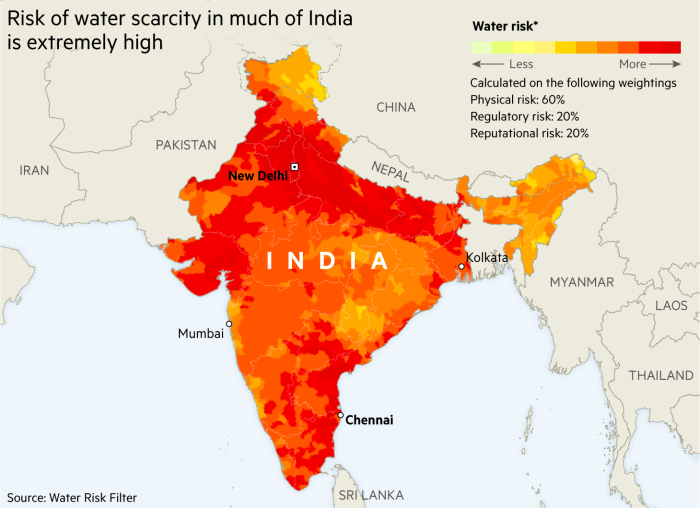

No end to crisis in sight as drought grips India’s Chennai – “The civil strife in this country will start from water, not from religion”

By Stephanie Findlay

3 August 2019

CHENNAI (Financial Times) – Murugan Sundaramurthy’s water business is buoyant. His fleet of tanker trucks have been fanning out across the countryside around Chennai for two decades, sucking water from boreholes and delivering it to homes to quench the city’s thirst.

But demand today is as high as he can remember, prompting him to add 500 more vehicles to his existing fleet of 4,500.

The public water supply, the supposed alternative for his customers, has been reduced to a trickle by a withering drought. But the shortages also reflect a pervasive problem across India: water management by the authorities that has been inadequate for years.

Rain or shine, Chennai depends on water trucks because officials have neglected to invest in water infrastructure while allowing developers to build on wetlands.

One result is rising communal tensions. Rural residents living near Chennai have staged violent protests to draw attention to complaints that their wells are being drained dry to supply the city by members of a “water mafia” such as Mr Sundaramurthy.

The businessman, who pays Rs400 ($5.75) for a tanker full of well water, argues that he supplies an essential service. “I agree that I am stealing water, that I am a robber, but the people drinking the water are also complicit in the crime,” he says.

The drought this year has been so severe that experts say a days-long deluge at the end of July will have had no impact. “The water levels in the reservoirs have dropped below 10 per cent, a few days of rain is not going to bring up the reservoir levels up,” said Arunabha Ghosh, chief executive officer of Council of Energy, Environment and Water, a non-profit policy research group based in Delhi, adding that the rain “does not solve chronic water mismanagement”. […]

“The civil strife in this country will start from water, not from religion,” said agricultural economist Ashok Gulati. “Over the next 10 to 20 years, the situation is going to worsen because it requires massive investment and I don’t think we prioritise water.” [more]