Refugees at “the highest level” seen by UN agency in its nearly 70-year existence – Record displacement shows “we’re almost unable to make peace”

19 June 2019 (UN News) – A record 70.8 million people fled war, persecution and conflict in 2018, UN refugee agency chief Filippo Grandi said on Wednesday, appealing for greater international solidarity to counter the fact that “we have become almost unable to make peace”.

Unveiling new data indicating that global displacement numbers are at “the highest level” that the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, has seen in its almost 70-year existence, Mr. Grandi noted that these were “conservative” estimates.

In Venezuela, he added, only half a million of the four million people that had left that country amid an ongoing economic and political crisis have formally applied for asylum and refugee status.

Some 37,000 people uprooted from homes every day in 2018

Of 41.3 million internally displaced people in 2018 – at a rate of 37,000 a day –some 13.6 million were newly displaced last year.

This included nearly 11 million individuals who were uprooted inside their country and 2.8 million new refugees and asylum-seekers, UNHCR’s data shows, as well as the fact that while richer countries hosted 16 per cent of refugees in 2018, least developed nations sheltered one in three.

The report also illustrates how fallout from conflict zones continues to drive displacement, with more than two-thirds of all refugees coming from just five countries: Syria (6.7 million), Afghanistan (2.7 million), South Sudan (2.3 million) Myanmar (1.1 million) and Somalia (900,000).

While calling for more funding to help countries deal with the impact of these increased migration flows – particularly in neighbouring crisis-hit States where most displacement victims are hosted – Mr. Grandi underlined the need for better regional and international cooperation in the face of “new conflicts, new situations producing refugees, adding themselves to the old ones”.

This remains a challenge, he said, given the lack of unity in the UN Security Council – “the international community’s supreme body for peace and security – “even when it discusses humanitarian matters in Yemen, in Libya”.

What we are seeing in these figures is further confirmation of a longer-term rising trend in the number of people needing safety from war, conflict and persecution.

Filippo Grandi, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

Citing the example of the 2016 Gambia conflict as the last one that he could remember being resolved – and where 50,000 Gambians returned to the country once it was safe – Mr. Grandi said that it proved “where there is a regional effort, an international effort, a conflict is addressed, people go back”.

In addition, Mr. Grandi dismissed numerous preconceptions about migrants and refugees “just taking advantage and seeking opportunities”, given that “half of the refugees … are children. That’s a very high proportion,” he said.

“When you hear a lot about refugees, people that are taking advantage, seeking opportunities. Children don’t flee to seek better opportunities; children flee because there is a risk and a danger.”

Officially last year, there were more than 138,000 unaccompanied and separated children globally, according to UNHCR’s report, which notes that this is likely a significant underestimate.

Peru restrictions risks creating ‘bottleneck’ upstream

Amid reports that regional neighbour Peru had tightened restrictions on Venezuelans trying to cross its border after struggling to cope with the migrant influx, Mr. Grandi noted that the risk was that other countries closer to Venezuela – such as Ecuador and Colombia – might follow suit, creating a “bottleneck”.

“These are people who are escaping so it is difficult for them to get documents from their own country,” Mr. Grandi said, adding that such papers were also difficult to obtain in Colombia and Ecuador.

It was almost counter-intuitive to ask these Venezuelans who are “refugee or refugee-like” to present passports and visas, he insisted.

“Peru is the second-largest recipient of Venezuelans after Colombia, and they are really overwhelmed by the presence of all these people and they have my full sympathy for that,” Mr. Grandi told journalists.

“But we have been urging them to be just like Colombia and Ecuador and Brazil to keep their borders open, because these people really are in need of safety, or protection,” he said.

Venezuela displacement pressures reminiscent of Europe in 2015

Drawing parallels with Europe’s recent, so-called refugee crisis, when hundreds of thousands of people fleeing wars, including the Syrian conflict, risked their lives crossing treacherous Mediterranean waters to reach Greece and Italy, the UNHCR chief insisted that an open-door policy was essential.

“It’s a little bit like what happened in Europe in 2015 when you had one border closing after the other, and it’s the first country, Greece, as it was then – and which in this case would be Colombia, and maybe even now, because they cannot bear the burden any more …so there’s a lot of risks in this and I would like to use this opportunity to appeal to those countries; I know we are asking them a lot, but it is my job to appeal to those countries to keep the borders open.”

According to UNHCR’s Global Trends report, displacement levels today are double what they were 20 years ago, confirming a long-term rising trend in the number of people in need of international protection.

Record displacement shows ‘we’re almost unable to make peace’, warns UN refugee agency chief

The world now has a population of 70.8 million forcibly displaced people.

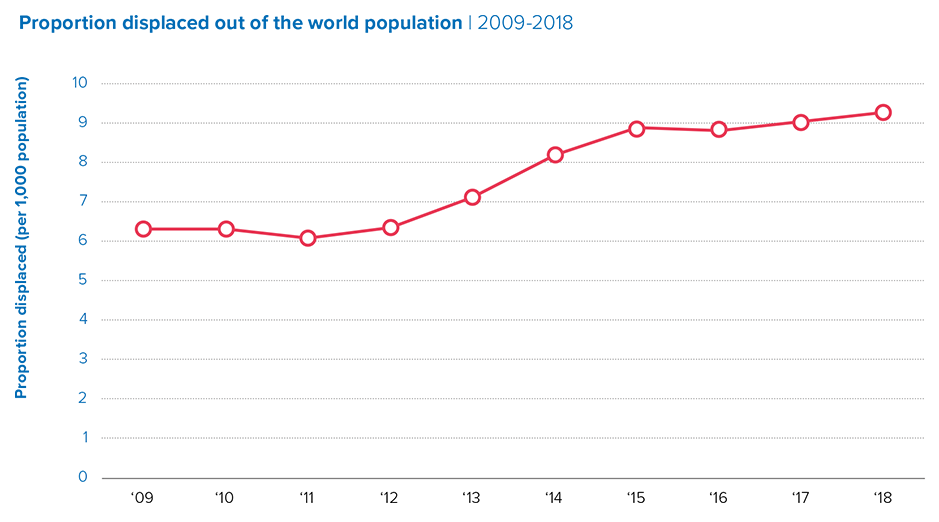

19 June 2019 (UNHCR) – The global population of forcibly displaced people grew substantially from 43.3 million in 2009 to 70.8 million in 2018, reaching a record high. Most of this increase was between 2012 and 2015, driven mainly by the Syrian conflict. But conflicts in other areas also contributed to this rise, including Iraq, Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and South Sudan, as well as the massive flow of Rohingya refugees from Myanmar to Bangladesh at the end of 2017.

The refugee population under UNHCR’s mandate has nearly doubled since 2012. In 2018, the increase was driven particularly by internal displacement in Ethiopia and asylum-seekers fleeing Venezuela. The proportion of the world’s population who were displaced also continued to rise, as the world’s forcibly displaced population grew faster than the global population.

13.6 million forced to flee in 2018

Large numbers of people were on the move in 2018. During the year, 13.6 million people were newly displaced, including 2.8 million who sought protection abroad (as new asylum-seekers or newly registered refugees) and 10.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs), who were forced to flee but remained in their own countries. This means that on every day of 2018, an average of 37,000 people were newly displaced. Many returned to their countries or areas of origin to try to rebuild their lives, including 2.3 million IDPs and nearly 600,000 refugees.

Some 1.6 million Ethiopians made up the largest newly displaced population during the year, 98 per cent of them within their country. This increase more than doubled the existing internally displaced population in the country.

Syrians were the next largest newly displaced population, with 889,400 people during 2018. Of these, 632,700 were newly displaced/registered outside the country, while the remainder were internally displaced. Nigeria also had a high number of newly displaced people with 661,800, of which an estimated 581,800 were displaced within the country’s borders. […]

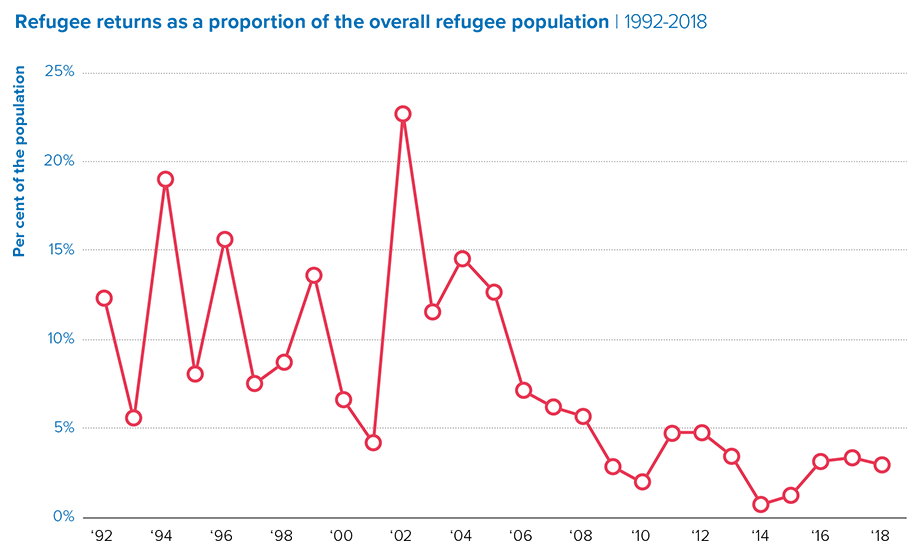

Returning home under safe conditions – the lasting solution of choice

During 2018, the number of refugees who returned to their countries of origin stood at 593,800, a decline from 2017. Voluntary repatriation remains the preferred lasting solution for the largest number of refugees and requires appropriate measures to ensure that this choice is made freely, without outside pressure. The choice to return must be based on accurate information about the conditions to be expected on arrival in the country of origin.

Over the years, UNHCR has worked with States to enable millions of refugees to return home, through:

- voluntary repatriation programmes,

- small-scale and individual repatriations, and

- ensuring that returns were sustainable.

In 2018, UNHCR observed a number of self-organized returns, sometimes under pressure, to areas where circumstances were partially improving but where peace and security were not fully established. For returns to be sustainable, it is critical they are not rushed and that the conditions for sustainable reintegration are met. However, all individuals have the right to make a personal decision to return voluntarily to their country of origin. When this happens, UNHCR monitors the progress of returns while also advocating for improved conditions.

Data show refugee returns to 37 countries of origin from 62 former countries of asylum during 2018. Data do not show whether these returns were safe, organized, and sustainable. [more]