Oil development in Ecuador’s Yasuni rainforest pits uncontacted tribes against one another – ‘After all the people we killed, we felt dizzy’

By Bethany Horne

3 January 2013 (Newsweek) – As two military-style helicopters touch down in a remote village in the jungles of Ecuador, masked men with guns hop out and scurry into a one-room schoolhouse. Inside they capture their target: a 6-year-old girl who doesn’t speak their language and can’t even guess why they are kidnapping her. They carry the terrified child, Conta, into the belly of one of the helicopters and it quickly rises up and away. Inside a thing she has only ever known as a screaming demon that roars across the sky, she is flown to a nearby city. There, she is taken by these armed strangers to a hospital that is a teeming petri dish of germs for which she has no immunity, since she has never been in a city before. This is the second time in seven months this girl, who grew up in a tribe without access to metal tools, has been violently wrenched from her daily life and thrust into a new and terrifying world. Conta is part of a small and little-known tribe called the Taromenane. Along with her little sister Daboka, Conta is one of two known survivors of a family group of uncontacted indigenous people – tribes who do not trade or communicate with any outsiders and violently reject all attempts by outsiders to do so with them – that lived in the Yasuni jungle in Ecuador. Experts think there are fewer than 200 uncontacted people living in the Yasuni, but very little is known about their location or their customs. Last March, the people in Conta’s family group, probably more than 20 in all, were massacred by warriors from a neighboring tribe, the Huaorani. Conta and Daboka were then taken as hostages by the men who killed their family. The facts regarding this horrific incident were widely known across Ecuador by early April, but eight months went by before the government even acknowledged them. For months, the government was either actively hiding the story, or hiding from it – officials cast doubt on whether there had been a massacre, and even on whether the Taromenane still existed. President Rafael Correa downplayed whatever happened that bloody day in March as just one of many conflicts between the tribes, not mentioning that it nearly led to the extinction of an entire ethnicity. The Huaorani warriors who took part in that massacre initially bragged on national television about their bravery – the systematic slaughter of dozens of naked and unarmed Taromenane men, women and children with rifles, pistols, and long spears – and sold photos to the highest bidder. However, after the attention they were getting turned negative, they went quiet, shut down access to their villages and threatened to run through with a spear any outsider who came near. Rather than prosecuting the murderers, or even investigating the massacre, the government built traditional thatch houses for the Huaorani families that had kidnapped Conta and Daboka – allegedly so the girls could live in a structure familiar to them. One of the Huaorani families was allowed to legally register Daboka as their adopted daughter. And then, in went the helicopters. Without warning, the Ecuadorean government snatched the girls back. Four days later, on November 30, Correa defended the armed extraction on national television, saying “the girl couldn’t be allowed to live with the murderers of her family,” and the crimes committed by the men who killed the Taromenane and kept the girls as trophies of war “can’t be left in impunity.” Six Huaorani were arrested, and now face charges of genocide. […]

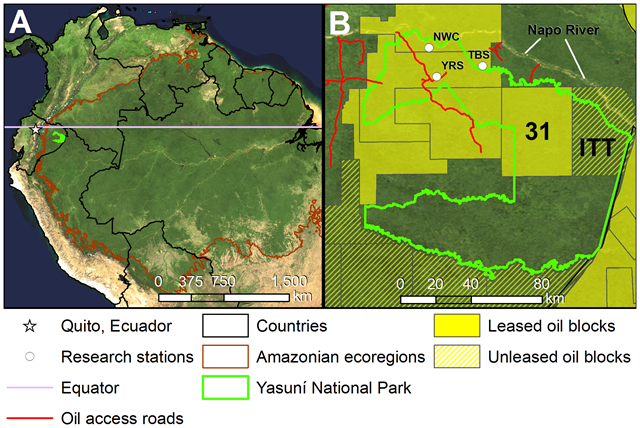

Land is at the heart of the decades-old conflict between the Taromenane and the Huaorani. Since the first oil boom in the 1960s and 1970s and the Huaorani tribe’s initial integration into mainstream Ecuadorean society, their population in the Amazon has exploded. The Huaorani now number more than 2,000, and their population boom has slowly pushed the Taromenane deeper into the jungle. The oil companies that the Huaorani allow into their territory, like Repsol, also create pressure. Ecuador’s indigenous confederation says that many of the conflicts over the years between the Huaorani and the Taromenane are due to the presence of oil companies. As the last tribe that still exclusively hunts and gathers to survive, the Taromenane are the most vulnerable to major changes to jungle land use, and their response when under pressure has been to attack. To kill. Oil workers, loggers, Huaorani, missionaries and other cowori, or outsiders, have all been killed by the spears of the uncontacted tribes since the colonization of the Amazon began. That’s clearly a problem, but the Taromenane aren’t supposed to have to fight to protect their land or their splendid isolation. The Ecuadorean Constitution declares that their lands are “irreducible and intangible,” that the state guarantees their voluntary remove from the rest of the world, and that any extractive activities on lands of the uncontacted tribes is to be considered ethnocide. Despite this constitutional protection, and mere months after the Huaorani massacre, the National Assembly voted to permit oil extraction in the Yasuni-ITT, a 200,000-hectare parcel that overlaps with the “intangible zone” set aside by law for the uncontacted tribes. To authorize that drilling project, the national assembly had to creatively reinterpret the constitution, and have triggered massive public opposition. The Yasuni-ITT section of the Yasuni National Park was always a highly politicized piece of land. Since Correa’s “21st century socialism” government was elected in 2007, the state has spent more than $1 million to promote the Yasuni ITT Initiative: a scheme for foreign governments and corporations to pledge money to spare the ITT from oil extraction. The Initiative hyped the ITT land as “the most biodiverse place on Earth” and home to thousands of endangered species, as well as uncontacted tribes. Here was the audacious offer to the world: If the ITT fund reached $3 billion by this year, half of what the 845 million barrels of crude underground Yasuni ITT is said to be worth, then Ecuador would not drill there. [more]

‘After all the people we killed, we felt dizzy’

Rather contradictory that they'd raise charges of genocide against tribes that have warred indefinitely, but permit oil companies to wipe out tens of thousands.

I guess it's all because of who butters your bread. It's not like they "care" about the indegineous. They never have.

Nobody does.

They're not "like us" and therefore, don't deserve protection – from us.