Graph of the Day: Index of climate-change risk preparation

18 November 2013 (World Bank) – Disasters trap people into poverty, as indicated by the evidence from many countries. For example, following the 2011 drought, poverty levels in Djibouti returned to levels above those in 2002, indicating a loss of almost 10 years of development gains. Studies from rural Ethiopia and Andhra Pradesh, India, indicate that drought is the most important factor in keeping people poor. China lists natural disasters among the eight key pressures undermining its progress in poverty reduction. And in Afghanistan, drought in the 1990s was identified as contributing to worsening food security and poverty a decade later (République de Djibouti 2011; Shepherd, et al. 2013; White 2004). Poor and marginalized households tend to be less resilient and face greater difficulties in absorbing and recovering from disaster impacts. Recurrent events also lead to compounding losses for many households, leading them to organize livelihoods in such a way that their overall risks are reduced in the face of uncertainty, even if it means a reduction in income and an increase in poverty (UNISDR 2009b). This is typically the case for farmers who hedge their risks against uncertain weather by planting well after the early rains, or by using less productive but more resilient varieties. To maintain basic food consumption, poor households may sell their limited remaining productive assets after disasters, often their only source of savings; others, however, may lower their food consumption. Both coping mechanisms can have long-term implications for human development, by affecting nutrition and children’s access to education and health (World Bank and GFDRR 2013). Due to limited opportunities and resources, the poor frequently accept higher levels of risk relative to their income, and live and/or work in informal settlements located in high-risk areas. In Dar es Salaam, Jakarta, Mexico City and São Paulo, those living in informal settlements are the most vulnerable to climate and disaster risks (World Bank 2011a). Overall, approximately 72% of Africa’s urban population lives in informal settlements, where investment in drainage infrastructure that can reduce flood risk is often lacking, and existing infrastructure is inadequately maintained (UNISDR 2009b). As a consequence, poor households must not only rebuild their assets after a disaster, but often bear the costs of reconstruction of public and social infrastructure, such as community schools, health clinics or local roads damaged by recurrent events. An example of this is in eastern and western Madagascar, where a single cyclone season can cause losses and damages to individual households equivalent to 10–30% of the average annual GDP per capita (Government of Madagascar 2008). Among the poor, disabled, elderly, orphans, widows and other vulnerable and marginalized groups are more likely to be affected by weather-related events. In many cases, women are more affected than men due to their lower mobility and cultural sensitivities that may prevent them from seeking livelihood opportunities away from high-risk areas, or to use shelters during extreme events. As a result, for example, some 91% of fatalities in Bangladesh after Cyclone Gorky were women (World Bank 2012c). Climate change could affect poverty targets directly, as well as indirectly, by curbing economic growth. Recent modeling studies indicate relatively modest impacts on global poverty— about 10 million additional poor under climate change scenarios by 2055, assuming steady annual economic growth of 2.2 percent (Skoufias 2012). However, Dell, et al. (2009) suggest that economic growth is also sensitive to temperature rises, which could, therefore, significantly increase the number of poor. Data from 134 countries, for example, indicated that temperature rises of 1°C were associated with a statistically significant reduction of about 9 percentage points in per capita GDP. A more recent study by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) also indicates significant numbers of poor living in hazard-prone countries by 2030 (Shepherd, et al. 2013). These global studies also suggest that an immediate reduction of greenhouse gases would only have a significant impact on poverty beyond 2100. This is due to the longevity of many greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and inertia in the climate system (IPCC 2013, World Bank 2012d), underscoring the urgent need to implement resilience—or adaptation—measures targeted towards the poor.

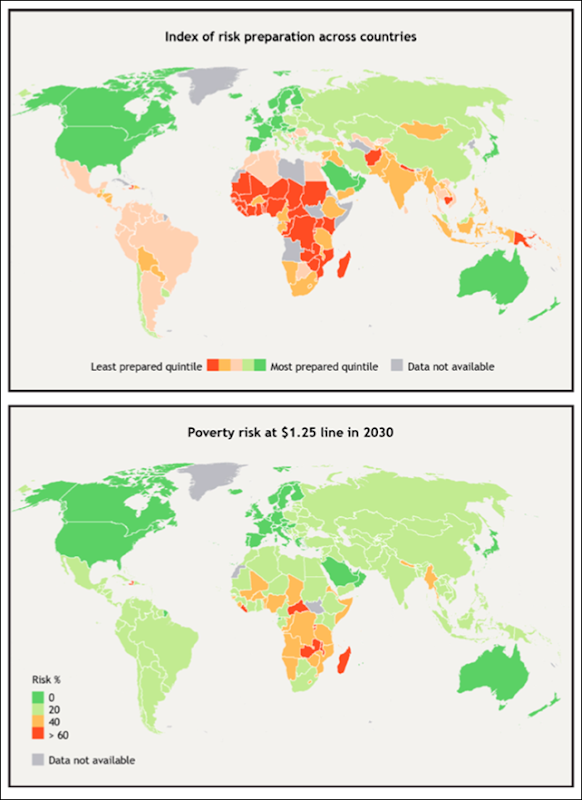

Weather-Related Loss & Damage Rising as Climate Warms