Ocean acidity: Small change, catastrophic results

By ANDREW SHARPLESS

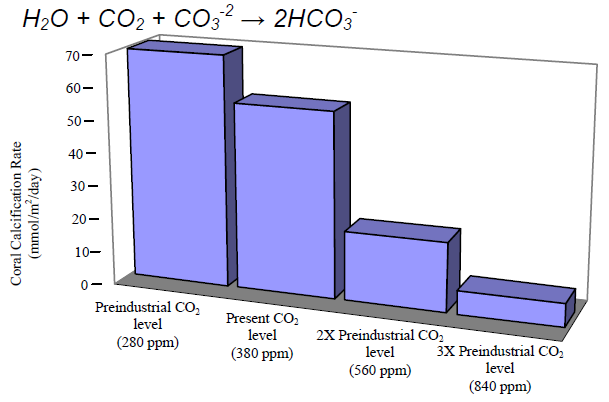

Tuesday, 01.18.11 Sometimes, seemingly small numbers can have remarkably big consequences. Miss a single free throw, and your team loses the championship. The economy slows by few percent, and millions of Americans are out of work. Your temperature rises by a degree or two, and you are down and out with a fever. Nowhere, however, are the big consequences of little numbers becoming clearer than in the health of our oceans. There, a chemical shift of just 0.1 that’s right, just one-tenth of a point – is already causing “ocean acidification,” a massive, fundamental change that has enormous implications for marine life. It may seem like this shift is no big deal. Don’t buy it: It’s actually another example of why seemingly little things do matter – and why the United States and other nations that attended the big climate change conference in Mexico last month need to do more to curb global warming. If you can’t recall your chemistry, here’s how it all works: Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, we’ve been burning enormous quantities of coal, oil and other fossil fuels. That has released vast clouds of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, where it has become the main gas that is warming the planet. Luckily for us, the oceans absorb about 30 million tons of carbon dioxide every day, slowing the pace of warming. Unfortunately, when carbon dioxide mixes with seawater, it spurs chemical reactions that can make the water more acidic, lowering what scientists call “the pH.” The sea’s pH can vary from place to place. But just a few hundred years ago, it was typically about 8.2. Today, due to all the carbon dioxide we’ve spewed into the atmosphere, it is about 8.1. It may seem that such a small change wouldn’t create a big problem, and that ocean ecosystems will cope just fine. The sad reality is that ocean acidification is a bigger problem than the number suggests. One reason is that, due to the way pH scales work, a 0.1 drop in pH is actually a 26 percent increase in acidity. Another is that this acidification has occurred with “startling” rapidity, scientists say – perhaps 100 times faster than anything Earth’s sea life has experienced in millions of years. Most worrying is that many living things are remarkably sensitive to rising acidity. If acid levels in our blood rise by 26 percent, for instance, we can become very sick indeed. Many kinds of sea creatures are equally vulnerable, especially in their egg and larval stages. And acidification can make it impossible for organisms such as corals, clams and crabs to sustain their hard skeletons and shells, since acids are corrosive and the acidification process can lock up the molecules they use as raw materials. These aren’t just theoretical threats. Already, ocean scientists are seeing just the kind of corrosive effects you would expect from acidification. Last year, for instance, one team reported in the prestigious journal Science that coral growth along Australia’s Great Barrier Reef had declined by 14 percent since 1990 – a “severe and sudden decline” unseen in centuries. Other studies have found that the shells of some “forams” – tiny creatures that are a key part of the marine food chain – are 30 percent lighter today than they were in the past. …

Ocean acidity: Small change, catastrophic results via Ocean Acidification