I wasn’t prepared to be a climate refugee – A climate advocate learns firsthand the price of climate change in our lives and calls for voters to head off future disasters – “My daughter is still having nightmares”

By Melissa Hanson

4 October 2024

(Scientific American) – I wasn’t prepared to be a climate refugee. Not after relocating my family from drought and wildfire-prone California to the “climate haven” of Asheville, N.C. But less than two months after we moved into our delightfully wooded, mild-weather community, we were forced to leave.

Even before our exodus, I already knew that November’s presidential election would be the most important of my life, with North Carolina playing a key role as a swing state. But Hurricane Helene made the stakes terrifyingly clear.

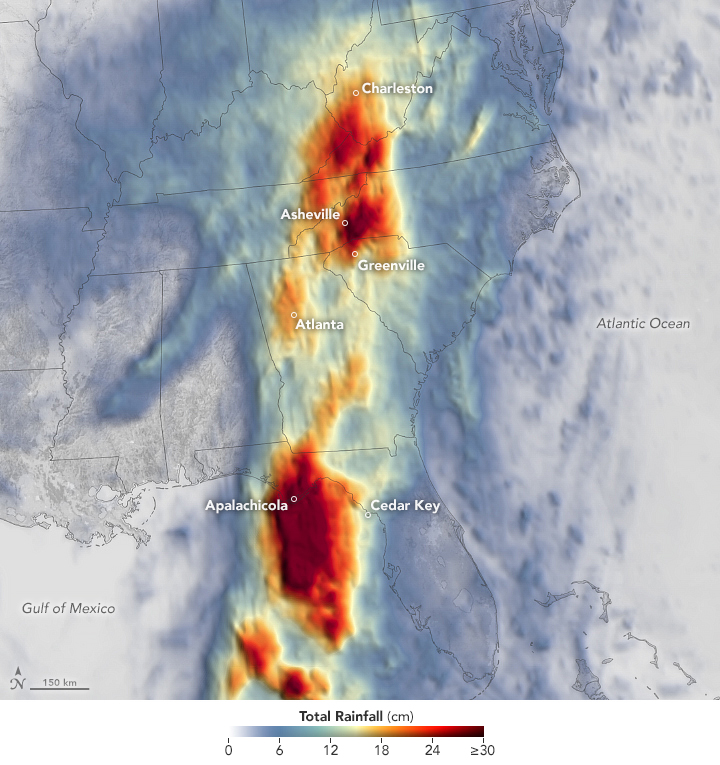

On Thursday, September 26, the hurricane made its way inland from the Gulf of Mexico through Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. Along its path, it ripped apart community after community. And then it hit western Appalachia. At 2,000 feet of elevation and 300 miles from the coast, Asheville is a place where people went to get away from devastating hurricanes.

That night, I couldn’t sleep. Trees crashed down around my home as emergency alerts blared on my phone. Power lines went down. Roads flooded. Mudslides ripped away homes. Despite being within a mile of the French Broad River, we were not told to evacuate ahead of the storm.

In the morning, after it seemed the worst had passed, a large pine tree crashed onto the roof directly above my young son’s bedroom while he was playing with LEGOs. He was thankfully unharmed, but it drove home the severity of what was happening around us. My young daughter clung to me saying over and over, “I’m scared.”

It was hard to get information about what was going on across Asheville. Within hours, we lost power, Internet and even cell service. A neighbor told me we could get info on the radio, so I sat in my car to listen to the local radio station’s updates. That’s how I learned that the water wasn’t safe to drink. The treatment plant was under eight feet of water and the distribution pipes had washed away.

When we heard it would take weeks or longer to restore basic services, I made plans for my family to leave town. We were lucky—we lived near the one highway that was open, and had a full tank of gas and a place to go. So on Sunday we left Asheville to stay with family on the Outer Banks.

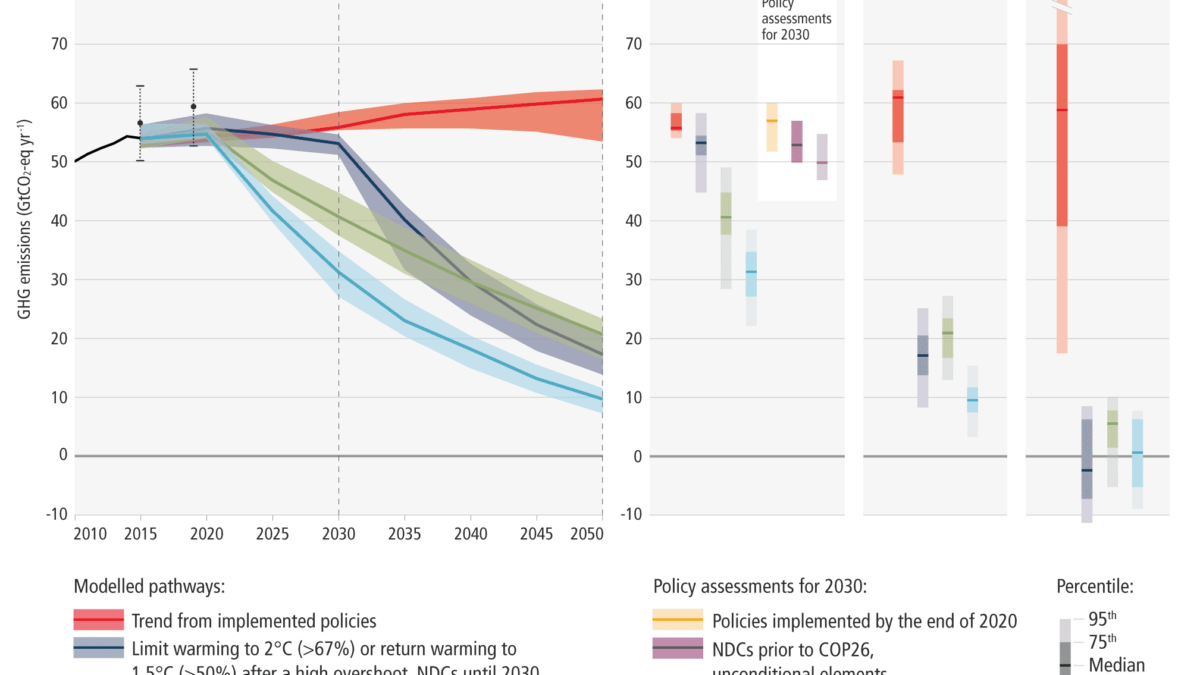

I work on climate change, and now I’m a climate refugee. I feel an urgent need to speak up and say: this was an unnatural disaster. Climate change, caused by burning fossil fuels, is making the planet hotter. The ocean absorbs much of this excess heat. As Hurricane Helene approached the coast of Florida, it gathered energy from unusually warm ocean water. Before the storm hit the coast, it went through a “rapid intensification” that transformed it into a major hurricane.

Warmer air is also wetter. For every one degree Fahrenheit increase, the atmosphere can hold 4 percent more moisture. Hurricane Helene dumped over two feet of rain in some parts of North Carolina. Scientists have already figured out that climate change caused Helene to dump 50 percent more rain in parts of Georgia and the Carolinas than it would have otherwise. The extreme levels of rainfall that we saw were 20 times more likely because we’ve warmed our planet.

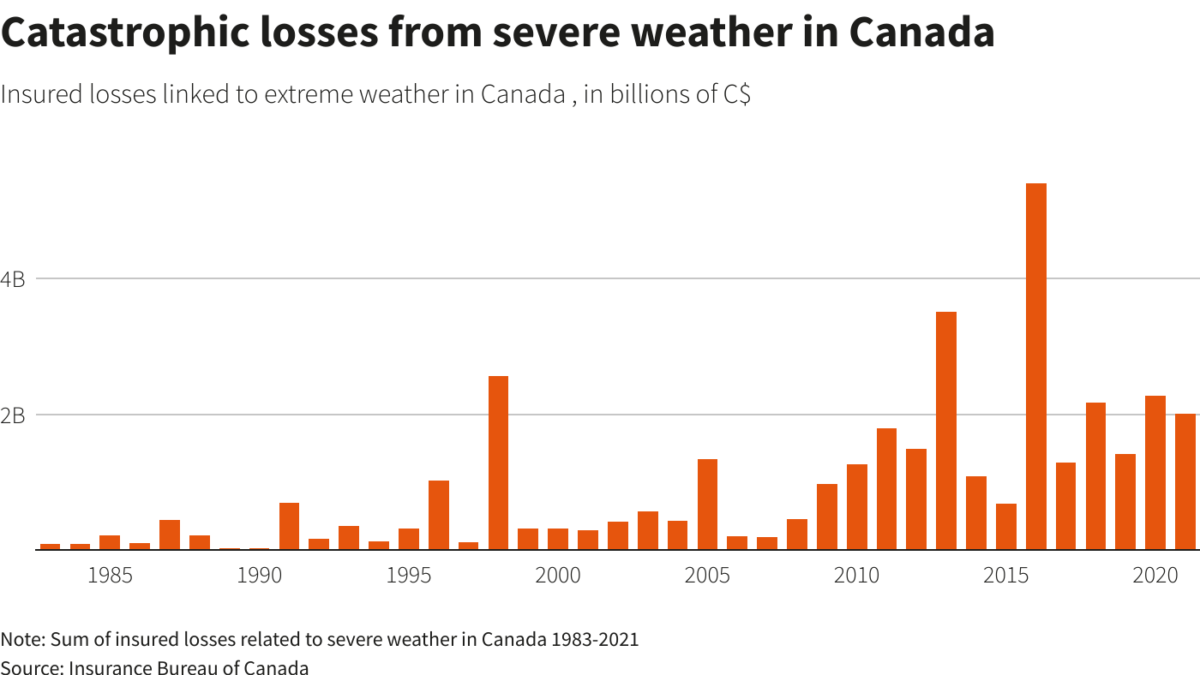

Once we had driven a few hours towards the coast, my cell phone started working again, and the full scale of devastation became clearer. Many others are still trapped, stuck between extreme flooding on one side and mudslides on the other. They are running out of water, food and essential supplies. Two million people in five states are still without power. Four days after the storm, emergency services remained in “search and rescue” mode. Hundreds of people are unaccounted for, and at least 199 have died. No doubt the death toll will continue to rise. It will take years and billions of dollars to recover.

Asheville was supposed to be one of those places where people were safer from climate disasters. It was listed in the top three cities in this country to escape climate impacts. It’s not Florida, where sea level rise threatens to drown coastal communities, or California, with its wildfires, or Arizona, battered with its record-breaking heat waves. But now I know firsthand that no place is safe from the climate crisis.

This disaster is a direct result of our failure to address the climate crisis. We must connect the dots between the images of houses floating away and the policies that support fossil fuels. And we need to think about how the people waiting in line for drinkable water are going to need to wait in line in just over a month for the election. Because our votes will matter enormously for the future of our country and our planet.

I will be voting for Kamala Harris. She has vowed to take action on the climate crisis and has a long history of holding big polluters accountable. Meanwhile Donald Trump has claimed that climate change is a “scam.” He has told Big Oil executives that if they donated $1 billion to his campaign, he will do their bidding. He has worked with the people behind Project 2025, which calls for gutting the National Weather Service—the very agency that allowed my family to prepare for the storm. Without their warnings, we wouldn’t have stocked up on water and food, and more of my neighbors would have died.

One candidate has a plan to address the crisis that caused Helene; the other plans to ignore it entirely.

Days later my daughter is still having nightmares. But I can see that even though she’s still a kid, she’s able to connect the dots. She asks me, “Why are humans doing this? Why is the smartest species on the planet still polluting the Earth? Why aren’t we fixing it?” And I struggle to give her answers.

I was not prepared to be a climate refugee. But my family and I are lucky to be refugees and not casualties. I hug my kids tight and tell them that it’s going to be okay. Because I believe that it’s not too late. On the heels of this horrifying disaster, I can make a choice that will make things better. Next month I can vote for a climate champion.

I Wasn’t Prepared to Be a Climate Refugee

I have been grieving for today’s children for decades. Now the science shows a great storm approaching, and it will involve us and our treatment of Mother Earth.

Asheville, NC has been considered a major flood risk for some time now, according to climate risk analysis.