We asked 380 climate scientists what they felt about the future – “Sometimes it is almost impossible not to feel hopeless and broken”

By Damian Carrington

8 May 2024

(The Guardian) – “Sometimes it is almost impossible not to feel hopeless and broken,” says the climate scientist Ruth Cerezo-Mota. “After all the flooding, fires, and droughts of the last three years worldwide, all related to climate change, and after the fury of Hurricane Otis in Mexico, my country, I really thought governments were ready to listen to the science, to act in the people’s best interest.”

Instead, Cerezo-Mota expects the world to heat by a catastrophic 3°C this century, soaring past the internationally agreed 1.5°C target and delivering enormous suffering to billions of people. This is her optimistic view, she says.

“The breaking point for me was a meeting in Singapore,” says Cerezo-Mota, an expert in climate modelling at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. There, she listened to other experts spell out the connection between rising global temperatures and heatwaves, fires, storms and floods hurting people – not at the end of the century, but today. “That was when everything clicked.

“I got a depression,” she says. “It was a very dark point in my life. I was unable to do anything and was just sort of surviving.”

Cerezo-Mota recovered to continue her work: “We keep doing it because we have to do it, so [the powerful] cannot say that they didn’t know. We know what we’re talking about. They can say they don’t care, but they can’t say they didn’t know.”

In Mérida on the Yucatán peninsula, where Cerezo-Mota lives, the heat is ramping up. “Last summer, we had around 47°C maximum. The worst part is that, even at night, it’s 38°C, which is higher than your body temperature. It doesn’t give a minute of the day for your body to try to recover.”

She says record-breaking heatwaves led to many deaths in Mexico. “It’s very frustrating because many of these things could have been avoided. And it’s just silly to think: ‘Well, I don’t care if Mexico gets destroyed.’ We have seen these extreme events happening everywhere. There is not a safe place for anyone.

“I think 3°C is being hopeful and conservative. 1.5°C is already bad, but I don’t think there is any way we are going to stick to that. There is not any clear sign from any government that we are actually going to stay under 1.5°C.”

Cerezo-Mota is far from alone in her fear. An exclusive Guardian survey of hundreds of the world’s leading climate experts has found that:

- 77% of respondents believe global temperatures will reach at least 2.5°C above preindustrial levels, a devastating degree of heating;

- almost half – 42% – think it will be more than 3°C;

- only 6% think the 1.5°C limit will be achieved.

The task climate researchers have dedicated themselves to is to paint a picture of the possible worlds ahead. From experts in the atmosphere and oceans, energy and agriculture, economics and politics, the mood of almost all those the Guardian heard from was grim. And the future many painted was harrowing: famines, mass migration, conflict. “I find it infuriating, distressing, overwhelming,” said one expert, who chose not to be named. “I’m relieved that I do not have children, knowing what the future holds,” said another.

The scientists’ responses to the survey provide informed opinions on critical questions for the future of humanity. How hot will the world get, and what will that look like? Why is the world failing to act with anything remotely like the urgency needed? Is it, in fact, game over, or must we fight on? They also provide a rare glimpse into what it is like to live with this knowledge every day.

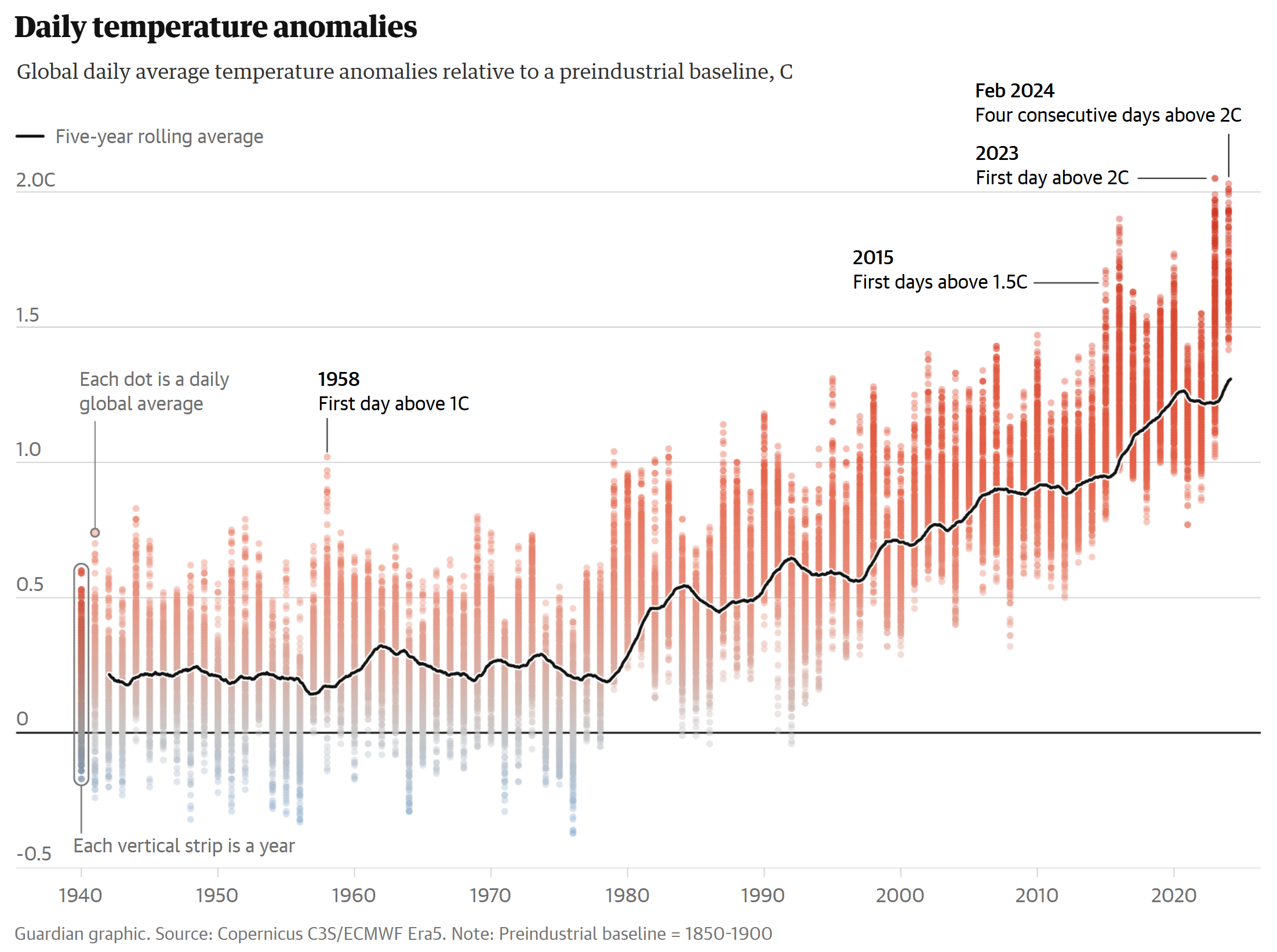

The climate crisis is already causing profound damage as the average global temperature has reached about 1.2°C above the preindustrial average over the last four years. But the scale of future impacts will depend on what happens – or not – in politics, finance, technology and global society, and how the Earth’s climate and ecosystems respond. […]

So how do the scientists cope with their work being ignored for decades, and living in a world their findings indicate is on a “highway to hell”?

Camille Parmesan, at the CNRS ecology centre in France, was on the point of giving up 15 years ago. “I had devoted my research life to [climate science] and it had not made a damn bit of difference,” she said. “I started feeling [like], well, I love singing, maybe I’ll become a nightclub singer.”

She was inspired to continue by the dedication she saw in the young activists at the turbulent UN climate summit in Copenhagen 2009. “All these young people were so charged up, so impassioned. So I said I’ll keep doing this, not for the politicians, but for you.

“The big difference [with the most recent IPCC report] was that all of the scientists I worked with were incredibly frustrated. Everyone was at the end of their rope, asking: what the fuck do we have to do to get through to people how bad this really is?”

“Scientists are human: we are also people living on this Earth, who are also experiencing the impacts of climate change, who also have children, and who also have worries about the future,” said Schipper. “We did our science, we put this really good report together and – wow – it really didn’t make a difference on the policy. It’s very difficult to see that, every time.”

Climate change is our “unescapable reality”, said Joeri Rogelj, at Imperial College London. “Running away from it is impossible and will only increase the challenges of dealing with the consequences and implementing solutions.”

Henri Waisman, at the IDDRI policy research institute in France, said: “I regularly face moments of despair and guilt of not managing to make things change more rapidly, and these feelings have become even stronger since I became a father. But, in these moments, two things help me: remembering how much progress has happened since I started to work on the topic in 2005 and that every tenth of a degree matters a lot – this means it is still useful to continue the fight.” […]

“It is the biggest threat humanity has faced, with the potential to wreck our social fabric and way of life. It has the potential to kill millions, if not billions, through starvation, war over resources, displacement,” said James Renwick, at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. “None of us will be unaffected by the devastation.”

“I am scared mightily – I don’t see how we are able to get out of this mess,” said Tim Benton, an expert on food security and food systems at the Chatham House thinktank. He said the cost of protecting people and recovering from climate disasters will be huge, with yet more discord and delay over who pays the bills. Numerous experts were worried over food production: “We’ve barely started to see the impacts,” said one. […]

“[Climate change] is an existential threat to humanity and [lack of] political will and vested corporate interests are preventing us addressing it. I do worry about the future my children are inheriting,” said Lorraine Whitmarsh, at the University of Bath in the UK. […]

The capture of politicians and the media by vastly wealthy fossil fuel companies and petrostates, whose oil, gas and coal are the root cause of the climate crisis, was frequently cited. “The economic interests of nations often take precedence,” said Lincoln Alves at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research. …

“The enormity of the problem is not well understood,” said Ralph Sims, at Massey University in New Zealand. “So there will be environmental refugees by the millions, extreme weather events escalating, food and water shortages, before the majority accept the urgency in reducing emissions – by which time it will be too late.” […]

“I believe in social tipping points,” where small changes in society trigger large-scale climate action, said Elena López-Gunn, at the research company Icatalist in Spain. “Unfortunately, I also believe in physical climate tipping points.”

Back in Mexico, Cerezo-Mota remains at a loss: “I really don’t know what needs to happen for the people that have all the power and all the money to make the change. But then I see the younger generations fighting and I get a bit of hope again.” [more]

We asked 380 climate scientists what they felt about the future…