Broken societies put people and planet on a collision course, says UNDP – “No country in the world has yet achieved very high human development without putting immense strain on the planet”

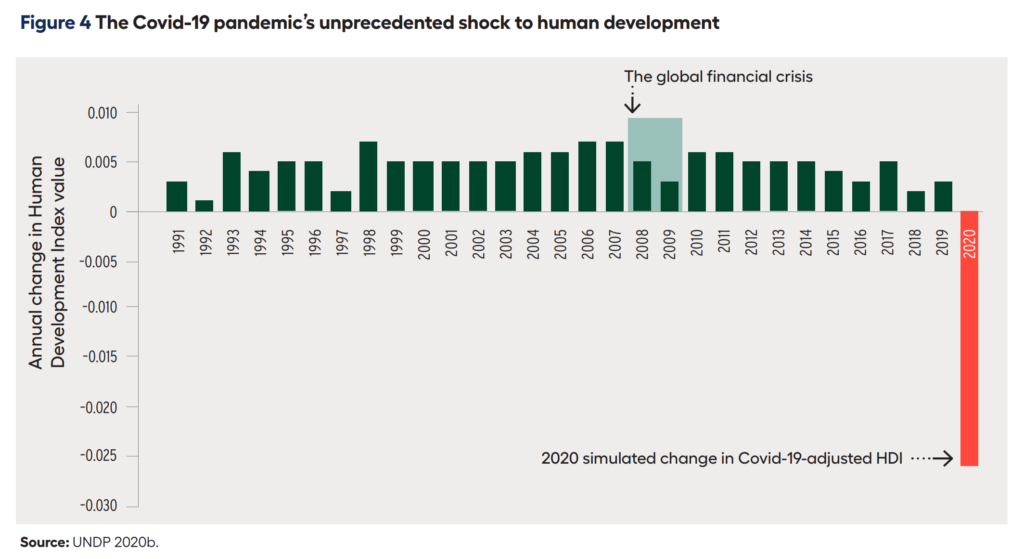

NEW YORK, 15 December 2020 (HDRO) – The COVID-19 pandemic is the latest crisis facing the world, but unless humans release their grip on nature, it won’t be the last, according to a new report [pdf] by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which includes a new experimental index on human progress that takes into account countries’ carbon dioxide emissions and material footprint.

The report lays out a stark choice for world leaders – take bold steps to reduce the immense pressure that is being exerted on the environment and the natural world, or humanity’s progress will stall.

“Humans wield more power over the planet than ever before. In the wake of COVID-19, record-breaking temperatures and spiraling inequality, it is time to use that power to redefine what we mean by progress, where our carbon and consumption footprints are no longer hidden,” said Achim Steiner, UNDP Administrator.

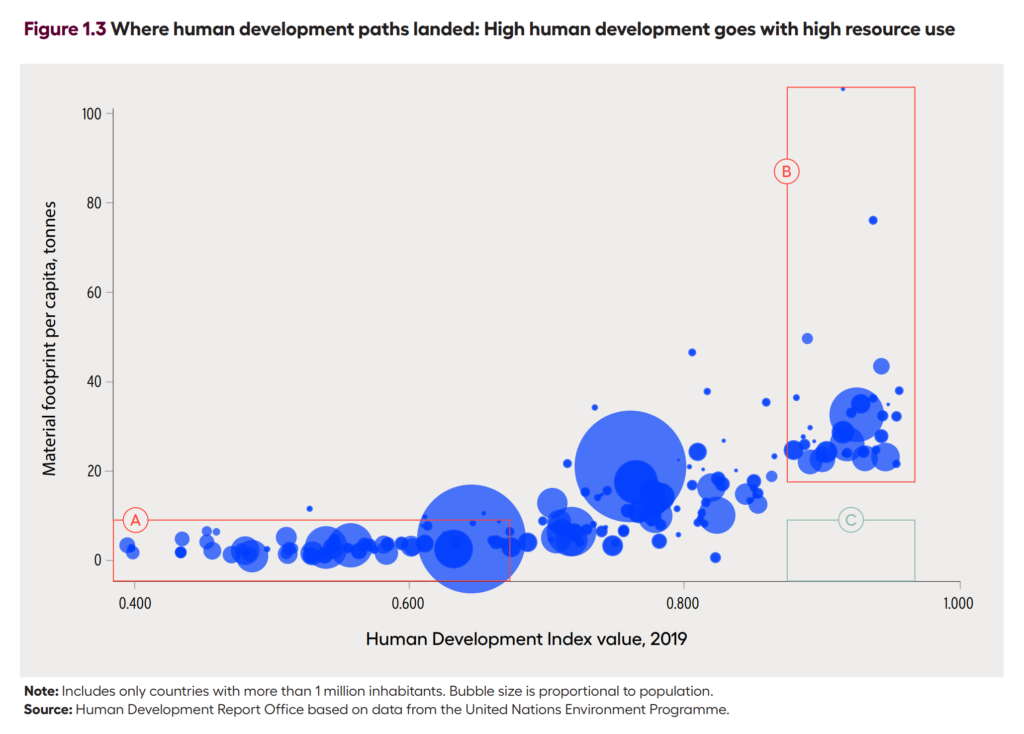

“As this report shows, no country in the world has yet achieved very high human development without putting immense strain on the planet. But we could be the first generation to right this wrong. That is the next frontier for human development,” he said.

The report argues that as people and planet enter an entirely new geological epoch, the Anthropocene or the Age of Humans, it is time to for all countries to redesign their paths to progress by fully accounting for the dangerous pressures humans put on the planet, and dismantle the gross imbalances of power and opportunity that prevent change.

To illustrate the point, the 30th anniversary edition of the Human Development Report, The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene, introduces an experimental new lens to its annual Human Development Index (HDI).

By adjusting the HDI, which measures a nation’s health, education, and standards of living, to include two more elements: a country’s carbon dioxide emissions and its material footprint, the index shows how the global development landscape would change if both the wellbeing of people and also the planet were central to defining humanity’s progress.

With the resulting Planetary-Pressures Adjusted HDI – or PHDI – a new global picture emerges, painting a less rosy but clearer assessment of human progress. For example, more than 50 countries drop out of the very high human development group, reflecting their dependence on fossil fuels and material footprint.

Despite these adjustments, countries like Costa Rica, Moldova, and Panama move upwards by at least 30 places, recognizing that lighter pressure on the planet is possible.

“The Human Development Report is an important product by the United Nations. In a time where action is needed, the new generation of Human Development Reports, with greater emphasis on the defining issues of our time such as climate change and inequalities, helps us to steer our efforts towards the future we want,” said Stefan Löfven, Prime Minister of Sweden, host country of the launch of the report.

The next frontier for human development will require working with and not against nature, while transforming social norms, values, and government and financial incentives, the report argues.

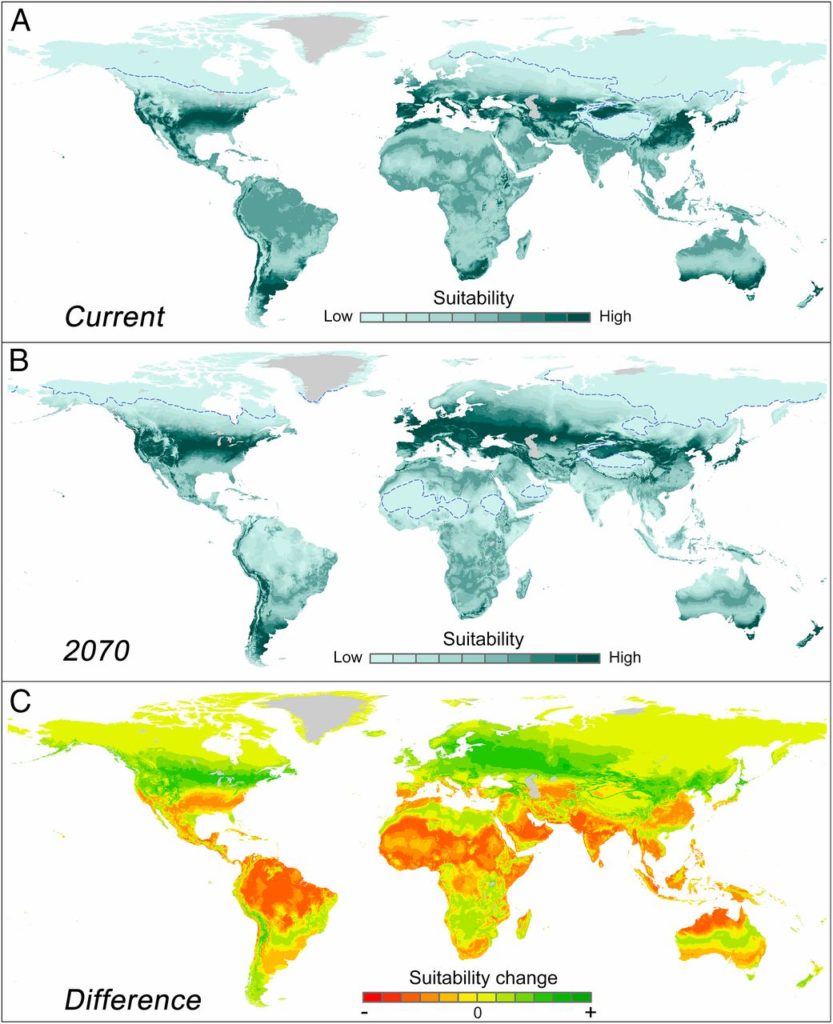

For example, new estimates project that by 2100 the poorest countries in the world could experience up to 100 more days of extreme weather due to climate change each year- a number that could be cut in half if the Paris Agreement on climate change is fully implemented.

And yet fossil fuels are still being subsidized: the full cost to societies of publicly financed subsidies for fossil fuels – including indirect costs – is estimated at over US$5 trillion a year, or 6.5 percent of global GDP, according to International Monetary Fund figures cited in the report.

Reforestation and taking better care of forests could alone account for roughly a quarter of the pre-2030 actions we must take to stop global warming from reaching two degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels.

“While humanity has achieved incredible things, it is clear that we have taken our planet for granted,” said Jayathma Wickramanayake, the UN Secretary-General’s Envoy Youth. “Across the world young people have spoken up, recognizing that these actions put our collective future at risk. As the 2020 Human Development Report makes clear, we need to transform our relationship with the planet — to make energy and material consumption sustainable, and to ensure every young person is educated and empowered to appreciate the wonders that a healthy world can provide.”

How people experience planetary pressures is tied to how societies work, says Pedro Conceição, Director of UNDP’s Human Development Report Office and lead author of the report, and today, broken societies are putting people and planet on a collision course.

Inequalities within and between countries, with deep roots in colonialism and racism, mean that people who have more capture the benefits of nature and export the costs, the report shows. This chokes opportunities for people who have less and minimizes their ability to do anything about it.

For example, land stewarded by indigenous peoples in the Amazon absorbs, on a per person basis, the equivalent carbon dioxide of that emitted by the richest 1 percent of people in the world. However, indigenous peoples continue to face hardship, persecution and discrimination, and have little voice in decision-making, according to the report.

And discrimination based on ethnicity frequently leaves communities severely affected and exposed to high environmental risks such as toxic waste or excessive pollution, a trend that is reproduced in urban areas across continents, argue the authors.

According to the report, easing planetary pressures in a way that enables all people to flourish in this new age requires dismantling the gross imbalances of power and opportunity that stand in the way of transformation.

Public action, the report argues, can address these inequalities, with examples ranging from increasingly progressive taxation, to protecting coastal communities through preventive investment and insurance, a move that could safeguard the lives of 840 million people who live along the world’s low elevation coastlines. But there must be a concerted effort to ensure that actions do not further pit people against planet.

“The next frontier for human development is not about choosing between people or trees; it’s about recognizing, today, that human progress driven by unequal, carbon-intensive growth has run its course,” said Pedro Conceição.

“By tackling inequality, capitalizing on innovation and working with nature, human development could take a transformational step forward to support societies and the planet together,” he said.

To learn more about the 2020 Human Development report and UNDP’s analysis on the experimental Planetary Pressures-Adjusted HDI, visit http://hdr.undp.org/en/2020-report

Broken societies put people and planet on collision course, says UNDP

One Response

Comments are closed.