Devastated by worst drought in decades and economic turmoil, many in Afghanistan near starvation – “It is the speed, scale and source of the crisis that is so extreme”

By Holly Rosenkrantz

3 April 2022

(USA TODAY) – Afghanistan has faced grave hunger crises before. Two decades ago, people in the country were so hungry they resorted to eating wild grass.

But the situation in the country now is unprecedented.

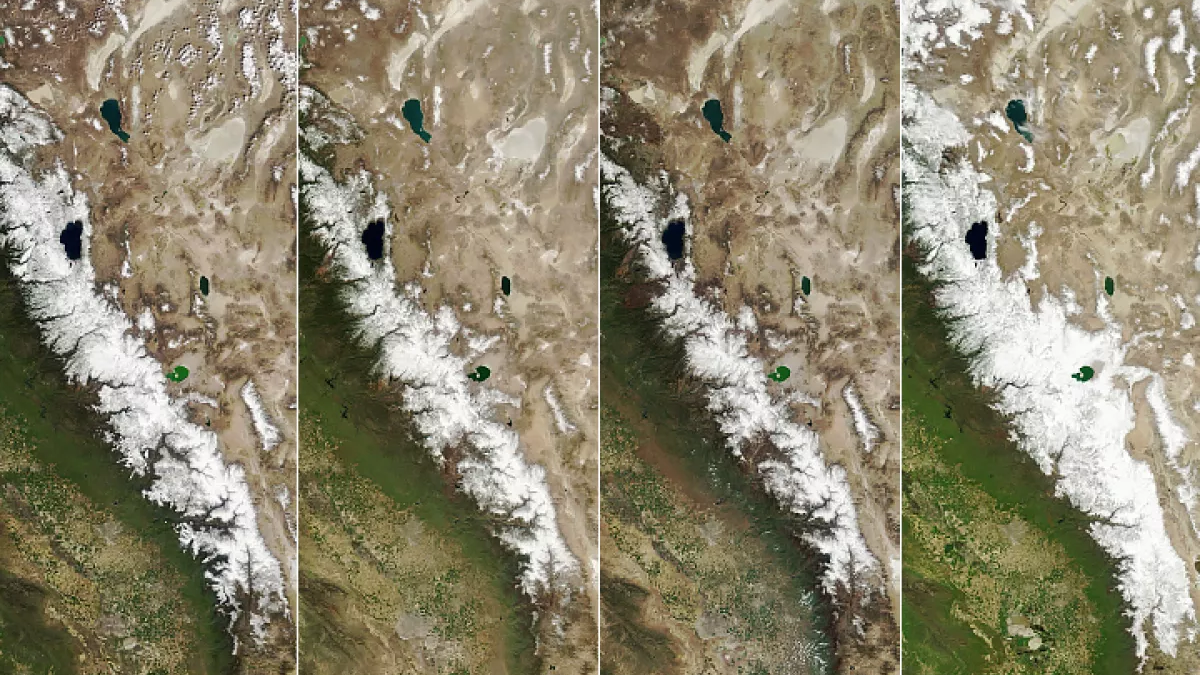

Exacerbated by an unusually cold winter and the worst drought in decades, the economic upheaval that came with the Taliban takeover has left 95% of Afghans without enough food. Nine million people are at risk of starvation. Hospitals are full of premature and dying babies, some weighing less than 2 pounds. A new class of urban people are hungry for the first time, as civil servants and teachers stand in line for food and cash assistance.

“Afghans are facing the toxic combination of a brutal winter, a frozen economy and famine risk,” said Amanda Catanzano, the International Rescue Committee’s acting vice president of policy and advocacy.

“With each month that goes by, more Afghans are forced to resort to the unimaginable to survive,” she said. “Parents are being forced to make decisions no one should have to consider, including selling off young daughters, so they can buy food for the rest of their children.”

“It is catastrophic,” said Laila Haidari, a former restaurant owner in Kabul who works with girls on their education. “You can see malnutrition in the children everywhere. There are dozens and dozens of people standing in front of bakeries, just begging for help and begging for some basic bread. They line the roads.”

A shattered economy

When the Taliban seized control of Afghanistan, the United States and other countries halted international aid and froze Afghanistan’s assets – sending the economy into a free fall.

Marzia lost her job washing clothes in people’s houses, and her husband lost his job in a bakery. With nine mouths to feed in her home – including four children and other relatives – Marzia’s family often eats just one meal a day. They turned to donations from the International Rescue Committee to help them stay alive.

Marzia received 26,000 afghanis as part of the IRC’s winter cash program to help her prepare for the winter. (That equals about $294.)

USA TODAY is not using Marzia’s full name for safety reasons.

It’s not enough money to feed everyone. When parents are sick and sometimes unable to walk, it is hard to make the funds cover the barest of needs.

“There are so many challenges preparing food for our family,” she said in a phone interview from Kabul.

When a finance executive in Kabul – not named for his protection – went to visit relatives, he found the children in the family unable to talk. “They hadn’t eaten anything in 48 hours,” he said.

A record number of Afghans are going hungry

The number of people who don’t have enough to eat is the highest recorded in Afghanistan and the largest globally. Food prices have soared. Since June, the price of wheat flour jumped 53%, cooking oil rose 39% and sugar climbed 36%, according to the United Nations’ World Food Program. The country’s wheat harvest is likely to be as much as 25% below average this year, hurt by the drought and farmers abandoning their land in rural areas under extreme weather conditions.

Heavy snow blankets the country, making it tough to gather wood daily to burn for cooking. Basic staples of nutrition – dairy, meat, green vegetables and fruit – are nearly impossible to obtain. People skip meals, so they can save what food they have for the family members who need it most. Babies are particularly hard hit; 1 million children are in danger of dying from malnutrition.

“It is the speed, scale and source of the crisis that is so extreme,” said Jacob Kurtzer, director and senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Humanitarian Agenda. “Previous hunger emergencies in Afghanistan and elsewhere have been the result of climate factors which are a slow onset, but you can see it coming.”

“What makes Afghanistan’s situation so tragic is that its humanitarian crisis, as bad as it is, doesn’t represent the full extent of the problem,” said Michael Kugelman, deputy director and senior associate for South Asia at the Wilson Center. “Afghanistan has a broken economy that’s on the verge of collapse. The country is dangerously low on liquidity, there’s little money in the country, and not much relief is in sight because the international financial aid on which Afghanistan heavily depends has been reduced to a trickle, because of sanctions.

“This means that even if the humanitarian crisis abates, a bigger problem looms. And in fact, so long as the liquidity problems aren’t addressed, the humanitarian situation won’t truly improve. In effect, food aid and other humanitarian support, as vital as they are, won’t amount to more than a band-aid if more isn’t done.” [more]

Devastated by drought and economic turmoil, many in Afghanistan near starvation