Trump E.P.A. updates plan to limit science used in environmental rules – “They’re putting in nonscientific criteria to decide what science the agency can use”

By Lisa Friedman

4 March 2020

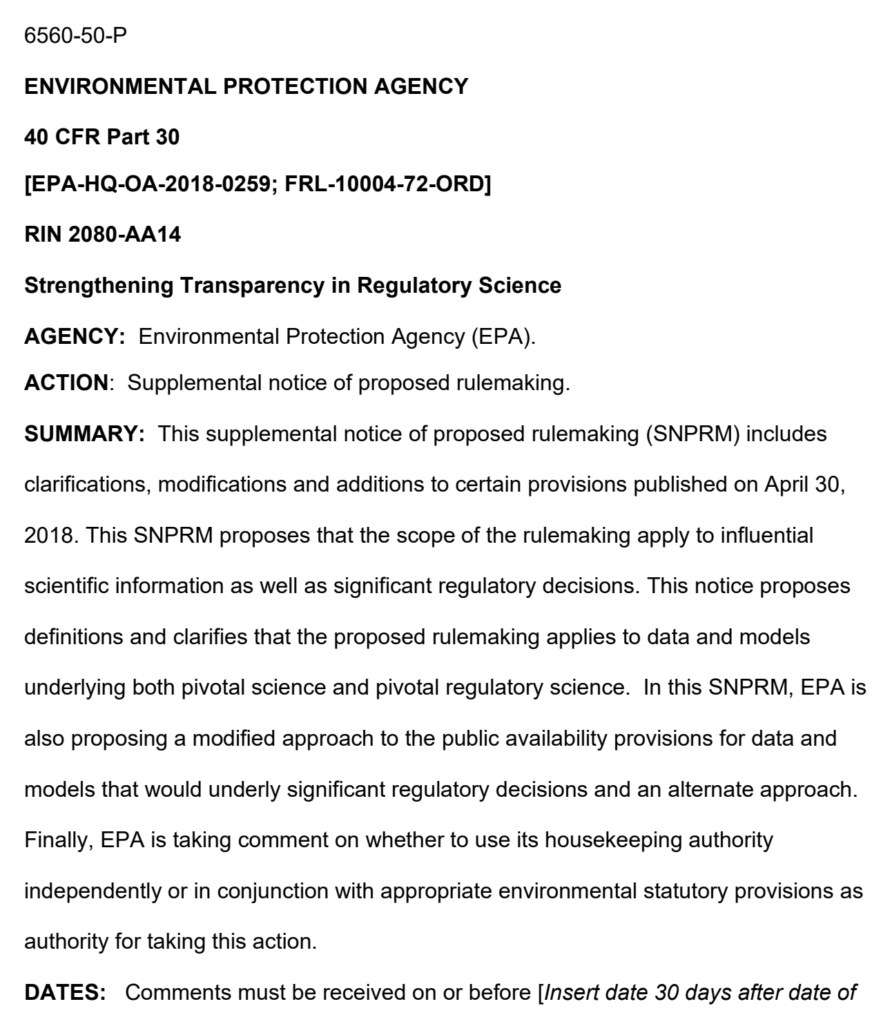

WASHINGTON (The New York Times) – The Trump administration has formally revised a proposal that would significantly restrict the type of research that can be used to draft environmental and public health regulations, a measure that experts say amounts to one of the government’s most far-reaching restrictions on science.

The revisions made public Tuesday evening mean the Environmental Protection Agency would give preference to studies in which all underlying data is publicly available. That slightly relaxed restrictions in an earlier draft that would have flatly excluded any research that did not offer up its raw data, even if that data included medical information protected by privacy laws or confidentiality agreements.

Even with the latest changes, scientists warned that the regulation would let the federal government dismiss or downplay some of the most important environmental research of the past decades. That includes research that definitively linked air pollution to premature deaths but relied on the personal health information of thousands of study subjects who had been guaranteed confidentiality.

The proposal is one of dozens of environmental protection rollbacks that the Trump administration is scrambling to finalize before the presidential election in November. It caps more than three years of efforts to dilute scientific research, especially on climate change and air pollution, which has underpinned rules that the fossil fuel industry calls burdensome. […]

Critics of the proposal, including the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the world’s largest general scientific society, argued that the administration’s real goal was to raise suspicions about the bedrock studies that helped establish modern regulations governing clean air and water. […]

Several critics of the plan noted that many existing regulations come up for renewal or reconsideration every few years, so even longstanding rules could be subject to the restrictions. Andrew Rosenberg, director of the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said benchmark science like Harvard’s Six Cities air pollution study might soon be deemed inadmissible.

“They’re putting in nonscientific criteria to decide what science the agency can use,” Mr. Rosenberg said. “Now the most important thing is whether the data is public, not the strength of the scientific evidence.”

The fresh revisions give the E.P.A. administrator the discretion to consider a study that has not made all its personnel and other data public. But Mr. Rosenberg said that would only take scientific decision-making out of the hands of scientists and hand it to a politically appointed administrator.

“It makes it easier for industry in most cases to say, ‘There’s too much uncertainty; you shouldn’t move forward,’” he said.

In January 2020 an advisory panel of Mr. Trump and Mr. Wheeler’s own scientists criticized the so-called transparency proposal, saying the E.P.A. “has not fully identified the problem to be addressed” by the new rule. When the plan is inevitably challenged in court, legal experts said, a judge was also likely to ask what health problem the agency sought to solve by enacting the regulation. [more]

E.P.A. Updates Plan to Limit Science Used in Environmental Rules