Leopards have lost 75 percent of their historic range globally – ‘Our next steps in this very moment will determine the leopard’s fate’

5 May 2016 (Discovery News) – Worldwide, leopards have lost about 75 percent of their historic range, according to a new survey – the first to attempt to get a glimpse of the big cat’s remaining global paw print. The analysis was produced by a group of partner organizations, including the National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Panthera. The researchers, whose findings have been published in the journal PeerJ, studied more than 1,300 sources containing information on the cat’s current and historic ranges. Meanwhile, mapping firm BIOGEOMAPS reconstructed the animal’s historic range and overlaid it with the current assessments. “This allowed us to compare detailed knowledge on its current distribution with where the leopard used to be and thereby calculate the most accurate estimates of range loss,” said the firm’s Peter Gerngross, who co-authored the study, in a statement. The results painted a grim picture for the standard-bearer leopard Panthera pardus and its nine subspecies (also included in the range analysis). The study found that the leopard’s range today occupies 3.3 million square miles (8.5 million square kilometers) – down from its historic range of 13.5 million square miles (35 million square kilometers). “Our results challenge the conventional assumption in many areas that leopards remain relatively abundant and not seriously threatened,” said lead author Andrew Jacobson, of the ZSL, who added that the leopard’s notoriously elusive nature may have helped hide evidence of its decline. The team notes a near disappearance of leopards in several parts of Asia as well as continued struggles of the animal in Africa, especially in the north and west of the continent. [more]

Leopards Have Lost 75 Percent of Their Historic Range

WASHINGTON, 4 May 2016 (Panthera) – The leopard (Panthera pardus), one of the world’s most iconic big cats, has lost as much as 75 percent of its historic range, according to a paper published today in the scientific journal PeerJ. Conducted by partners including the National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative, international conservation charities the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Panthera and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Cat Specialist Group, this study represents the first known attempt to produce a comprehensive analysis of leopards’ status across their entire range and all nine subspecies. The research found that leopards historically occupied a vast range of approximately 35 million square kilometers (13.5 million square miles) throughout Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Today, however, they are restricted to approximately 8.5 million square kilometers (3.3 million square miles). To obtain their findings, the scientists spent three years reviewing more than 1,300 sources on the leopard’s historic and current range. The results appear to confirm conservationists’ suspicions that, while the entire species is not yet as threatened as some other big cats, leopards are facing a multitude of growing threats in the wild, and three subspecies have already been almost completely eradicated. Lead author Andrew Jacobson, of ZSL’s Institute of Zoology, University College London and the National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative, stated: “The leopard is a famously elusive animal, which is likely why it has taken so long to recognize its global decline. This study represents the first of its kind to assess the status of the leopard across the globe and all nine subspecies. Our results challenge the conventional assumption in many areas that leopards remain relatively abundant and not seriously threatened.” In addition, the research found that while African leopards face considerable threats, particularly in North and West Africa, leopards have also almost completely disappeared from several regions across Asia, including much of the Arabian Peninsula and vast areas of former range in China and Southeast Asia. The amount of habitat in each of these regions is plummeting, having declined by nearly 98 percent. Philipp Henschel, co-author and Lion Program survey coordinator for Panthera, stated: “A severe blind spot has existed in the conservation of the leopard. In just the last 12 months, Panthera has discovered the status of the leopard in Southeast Asia is as perilous as the highly endangered tiger.” Henschel continued: “The international conservation community must double down in support of initiatives protecting the species. Our next steps in this very moment will determine the leopard’s fate.” “Leopards’ secretive nature, coupled with the occasional, brazen appearance of individual animals within megacities like Mumbai and Johannesburg, perpetuates the misconception that these big cats continue to thrive in the wild — when actually our study underlies the fact that they are increasingly threatened,” said Luke Dollar, co-author and program director of the National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative. Co-author Peter Gerngross, with the Vienna, Austria-based mapping firm BIOGEOMAPS, added: “We began by creating the most detailed reconstruction of the leopard’s historic range to date. This allowed us to compare detailed knowledge on its current distribution with where the leopard used to be and thereby calculate the most accurate estimates of range loss. This research represents a major advancement for leopard science and conservation.” Leopards are capable of surviving in human-dominated landscapes provided they have sufficient cover, access to wild prey and tolerance from local people. In many areas, however, habitat is converted to farmland and native herbivores are replaced with livestock for growing human populations. This habitat loss, prey decline, conflict with livestock owners, illegal trade in leopard skins and parts and legal trophy hunting are all factors contributing to leopard decline. Complicating conservation efforts for the leopard, Jacobson noted: “Our work underscores the pressing need to focus more research on the less studied subspecies, three of which have been the subject of fewer than five published papers during the last 15 years. Of these subspecies, one — the Javan leopard (P. p. melas) — is currently classified as critically endangered by the IUCN, while another — the Sri Lankan leopard (P. p. kotiya) — is classified as endangered, highlighting the urgent need to understand what can be done to arrest these worrying declines.” Despite this troubling picture, some areas of the world inspire hope. Even with historic declines in the Caucasus Mountains and the Russian Far East/Northeast China, leopard populations in these areas appear to have stabilized and may even be rebounding with significant conservation investment through the establishment of protected areas and increased anti-poaching measures. “Leopards have a broad diet and are remarkably adaptable,” said Joseph Lemeris Jr., a National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative researcher and paper co-author. “Sometimes the elimination of active persecution by government or local communities is enough to jumpstart leopard recovery. However, with many populations ranging across international boundaries, political cooperation is critical.” NOTE: For access to National Geographic press-approved leopard imagery, please contact ckingwoo@ngs.org.CONTACT: Susie Weller Sheppard, Panthera, (347) 446-9904, sweller@panthera.org

About Panthera

Panthera, founded in 2006, is devoted exclusively to the conservation of wild cats and their landscapes, which sustain people and biodiversity. Panthera’s team of preeminent cat biologists develop and implement science-based conservation strategies for cheetahs, jaguars, leopards, lions, pumas, snow leopards and tigers. Representing the most comprehensive effort of its kind, Panthera works in partnership with NGOs, scientific institutions, communities, corporations and governments to create effective, replicable models that are saving wild cats around the globe.

About the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society is a global nonprofit organization driven by a passionate belief in the power of science, exploration, education and storytelling to change the world. The Society funds hundreds of research and conservation projects around the globe each year and works to inspire, illuminate and teach through scientific expeditions, award-winning journalism and education initiatives. The National Geographic Society’s Big Cats Initiative (BCI) was founded in 2009 with Explorers-in-Residence, filmmakers and conservationists Dereck and Beverly Joubert as a long-term effort to halt the decline of big cats in the wild. BCI supports efforts to save big cats through assessment activities, on-the-ground conservation projects and education. For more information, visit CauseAnUproar.org.

About the Zoological Society of London (ZSL)

Founded in 1826, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) is an international scientific, conservation and educational charity whose mission is to promote and achieve the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats. Our mission is realised through our ground-breaking science, our active conservation projects in more than 50 countries and our two Zoos, ZSL London Zoo and ZSL Whipsnade Zoo. For more information, visit www.zsl.org. Download a printable version of the press release.

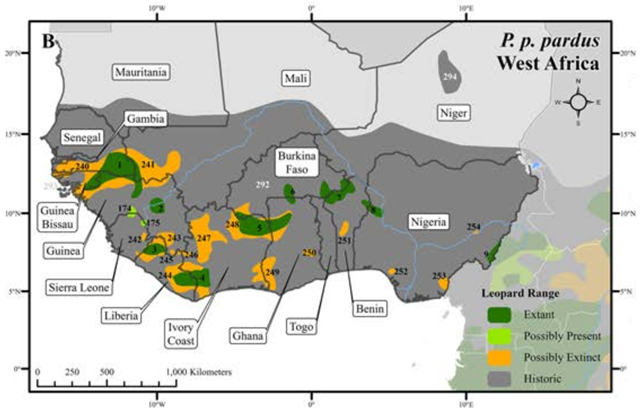

ABSTRACT: The leopard’s (Panthera pardus) broad geographic range, remarkable adaptability, and secretive nature have contributed to a misconception that this species might not be severely threatened across its range. We find that not only are several subspecies and regional populations critically endangered but also the overall range loss is greater than the average for terrestrial large carnivores. To assess the leopard’s status, we compile 6,000 records at 2,500 locations from over 1,300 sources on its historic (post 1750) and current distribution. We map the species across Africa and Asia, delineating areas where the species is confirmed present, is possibly present, is possibly extinct or is almost certainly extinct. The leopard now occupies 25–37% of its historic range, but this obscures important differences between subspecies. Of the nine recognized subspecies, three (P. p. pardus, fusca, and saxicolor) account for 97% of the leopard’s extant range while another three (P. p. orientalis, nimr, and japonensis) have each lost as much as 98% of their historic range. Isolation, small patch sizes, and few remaining patches further threaten the six subspecies that each have less than 100,000 km2 of extant range. Approximately 17% of extant leopard range is protected, although some endangered subspecies have far less. We found that while leopard research was increasing, research effort was primarily on the subspecies with the most remaining range whereas subspecies that are most in need of urgent attention were neglected.

Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range

"Next steps" are bloody obvious. Extinction for the leopards (and every other living creature – one by one). Humans do NOT care enough about the living biosphere to actually save it from our predatory destruction. Leopards, Lions, Elephants, and Rhino's will all be extinct within 20 years from today, along with most ocean life. Should any of these creatures be alive – they'll only be found in highly guarded enclosures, destined to die out as caged animals, never to be returned to the 'wild' (which will also be non-existent).

The proof of these claims is already found in the historical record, with 99.99% of all species having now gone extinct, with many at the hand of mankind since we mastered fire (the beginning of the Anthropocene). The diversity of life that has been lost is absolutely staggering – and there is absolutely no reason whatsoever to believe that humanity will suddenly gain consciousness, awareness, compassion or abandon profits and greed to "save the animals from extinction" (save them from humans in reality). We've had over 100,000 years to figure this out and still get it all wrong (and always will, it's not within us to be any different then we actually are).

History shows us what we truly are – the top predatory species responsible for virtually ALL of the destruction of the living biosphere by another species. We can pretend it isn't true, but it is, and we are not going to change (hopium isn't in my vocabulary anymore except when I point out the faulty reasoning of hope).

It's unbelievably tragic and sad that we cannot stop any of this, but that is the reality we must finally be forced to face as a species.

Everything on the planet is subject to human destruction and waste and we have done so much damage now and depleted so much of the biosphere this time (we've done it before) that extinction is the future of all living things (including the plants and non-sentient living things).

When it is all finally "done", only bacteria and molds and perhaps a few jellyfish will remain as the 'tolerant' (surviving) species of our waste and pollution that will have destroyed the planet and driven the climate into warp-speed (an unsurvivable hell on Earth) of overheating and extreme weather events.

No mammals of any kind will remain as they will not be able to survive the heat stress or the lack of food (plants will have also died off due to heat stress and drought / extreme weather / pollution including radioactive contamination from abandoned nuclear facilities that melted down for lack of human intervention).

The future is death – of the biosphere and everything within it. Pandora's Box has been opened and there is nothing to be done to close it now. This is exactly what some scientist predict and what is being ignored by the public which still clings to the hopium that we haven't fucked things up that badly. I'll side with the experts on this one.

So our "next steps" as feeble or as noble as they may be will not make any difference in the end. But what matters now is that we continue to try – despite the knowledge that it will never be enough.

There is no dignity in defeat or resignation "because we can't win", only shame. The species (humanity) needs to rise up as only this species can (none other can do it) and make the effort – at any cost, so that we may give as much life as we can to what remains, and bring awareness to the species (humans) that we are NOT the masters of this world (or anything else) and never will be. We are the DESTROYERS and always will be.

It will be in the destruction of the biosphere that we will finally recognize this truth of what we are. But we do NOT need to walk this path into our own death and extinction, which is just as inevitable as the extinction of everything else. The only dignity that remains is for us to try. In this humility and effort, we may finally regain what we lost long ago, an appreciation for life on this planet and what it means.