Athlete vs. heat: Scorching conditions are increasingly common at sporting events, creating risks and challenges for athletes – “It’ll be the hottest Summer Olympics in history”

By Rick Maese

15 July 2019

LOVELL CANYON, Nevada (The Washington Post) – It was 73 degrees and the early-morning sun was still rising over the Mojave Desert as nearly six dozen long-distance runners gathered at the start line and anxiously watched numbers tick down on the digital clock overhead.

“Make sure that you’re staying on top of your internal hydration and your external cooling,” the race organizer said into a microphone.

The runners shook their limbs loose and bobbed in place, eager for the start. The annual race is called Running with the Devil, and it takes place less than 30 miles from the glitzy air-conditioned casinos on the Strip in Las Vegas. The forecast called for an unseasonably cool day in the desert, but the racers — running a marathon, 50 kilometers, 50 miles or 100 kilometers — had assembled specifically for a physiological test in the heat.

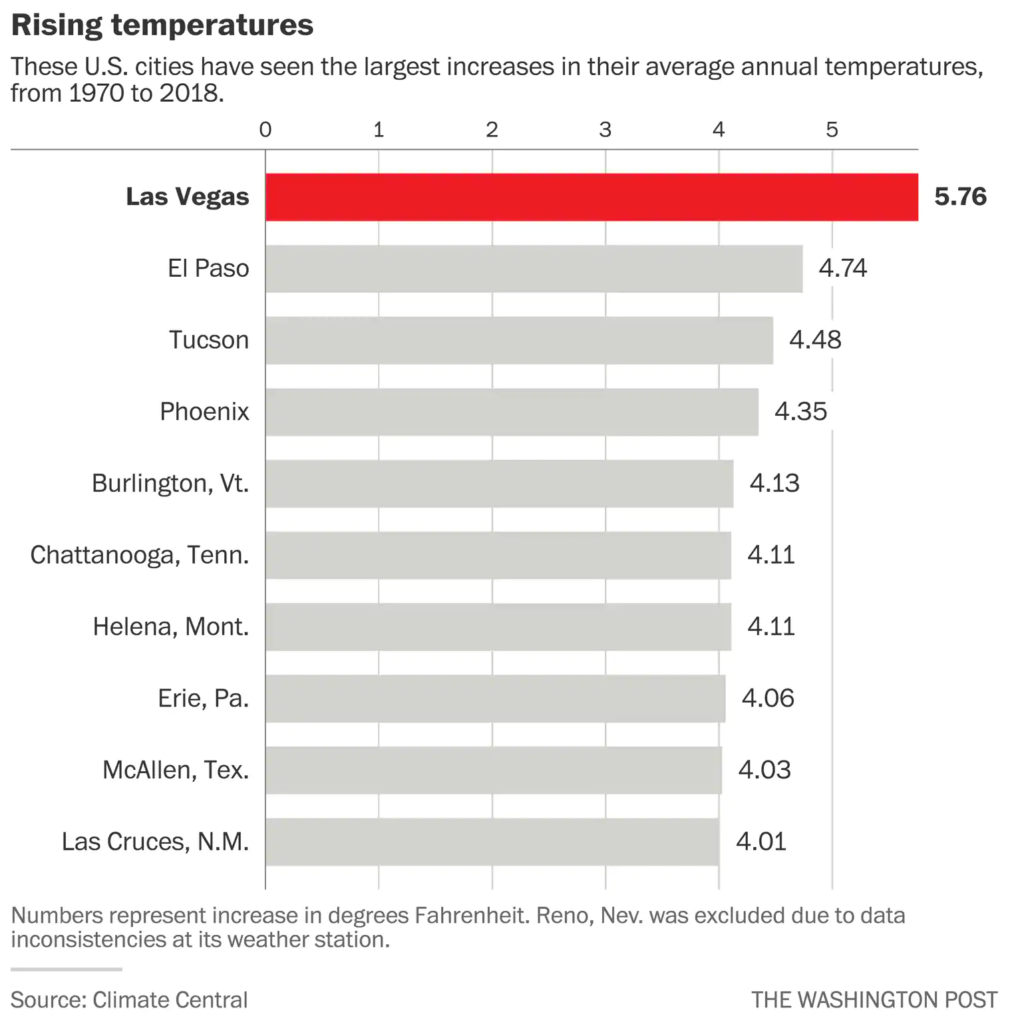

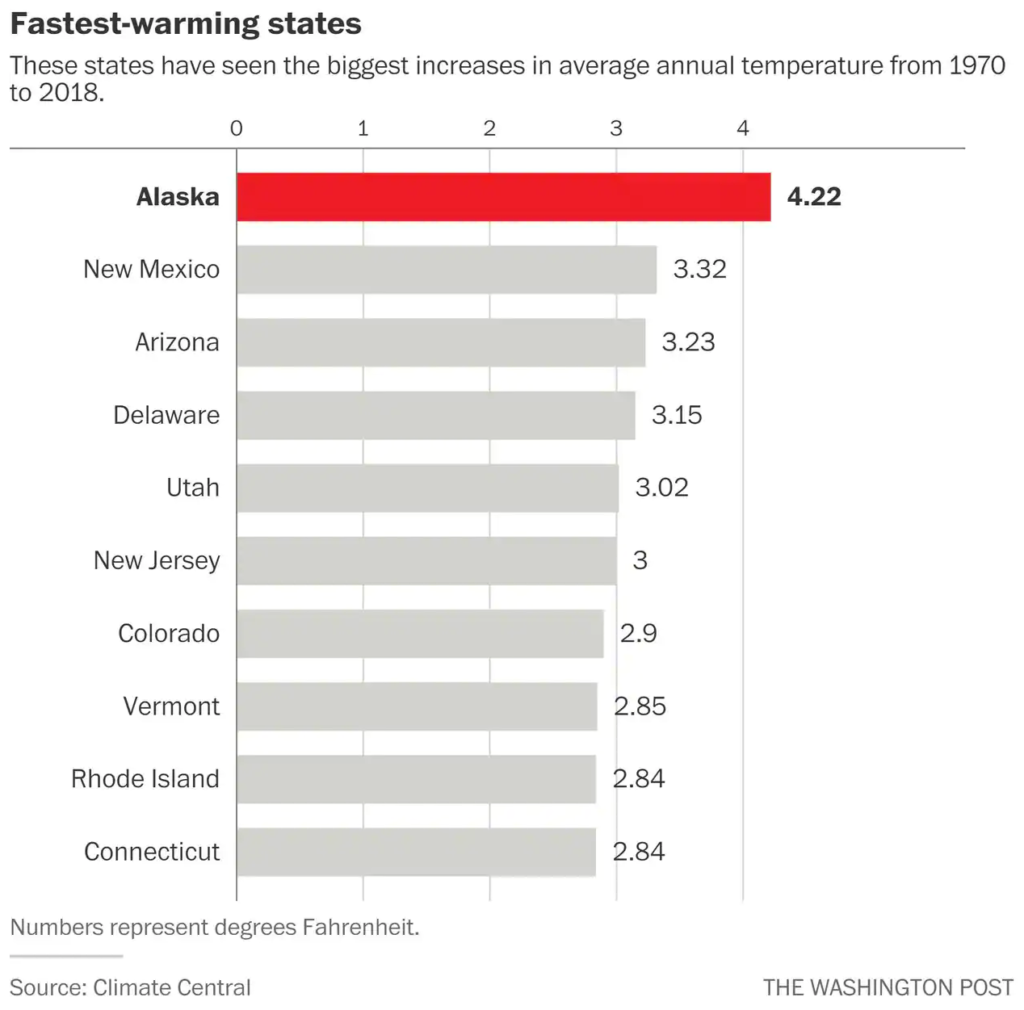

The people from this area are plenty acquainted with hot summer days. Climatologists say the earth’s hottest places are getting hotter faster than everywhere else. There was a report this year that found Las Vegas is the fastest-warming city in the country and has seen an average temperature increase of nearly 6 degrees since 1970.

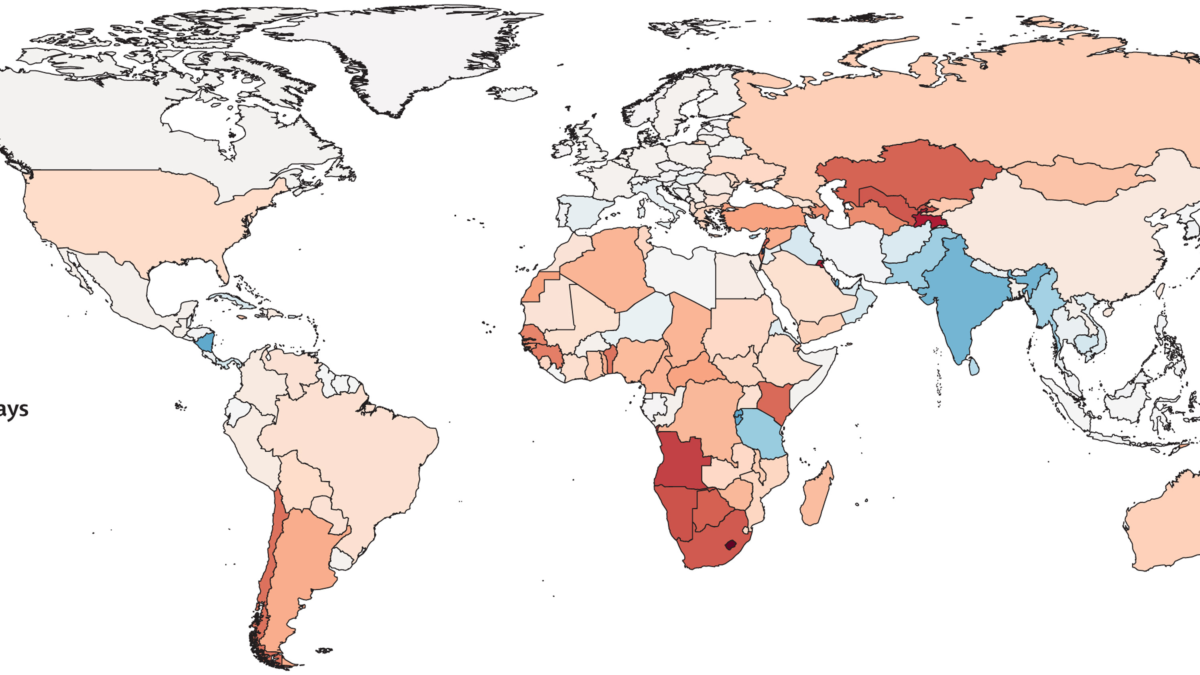

The whole planet is getting warmer, in fact. Across the globe, the past four years are the warmest on record. Last year the average temperature across Earth’s land and ocean surfaces was 1.42 degrees Fahrenheit above the 20th-century average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and climate watchers say it’s trending in one direction. Climate projections suggest the planet could warm by 3 or 4 degrees by the end of this century, which would have major ramifications for outdoor sports everywhere, from recreational weekend joggers to elite athletes competing on the biggest stages.

“When you talk about climate change and you tell someone it’s a degree hotter — Pfft! — that doesn’t seem like very much,” explained Andrew Grundstein, a climatologist at the University of Georgia. “When I talk to my students about the difference in a couple degrees, I tell them, ‘Remember, when it was four degrees cooler, we were in an ice age.’ ” […]

Heat-related topics have become a staple of the annual meetings, and about 200 people — athletic trainers, doctors, researchers, physiologists and performance coaches among them — gathered in Room 303 for a presentation focused on next summer’s Olympics. Doug Casa, head of the Korey Stringer Institute who serves on a commission dedicated to heat-related issues for the Tokyo Games, offered the crowd a brief history lesson.

“The 1964 Tokyo Olympics, they moved to October because of the brutal heat in Tokyo,” he said. “Well, it’s hotter in Tokyo now than it was back in 1964. … There’s no movement this year. It’s happening at the end of July and August in the most brutal conditions that you can imagine.”

With an anticipated average temperature of nearly 90 degrees and humidity topping 55 percent, the Olympics will be on par with some of the hottest athletic events ever staged.

“It’ll be the hottest Summer Olympics in history,” he said. “It’s pretty extreme.” [more]