Trump officials deleting mentions of “climate change” from U.S. Geological Survey press releases – “It’s an insult to the science”

By Scott Waldman

8 July 2019

(Science) – A March news release from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) touted a new study that could be useful for infrastructure planning along the California coastline.

At least that’s how President Donald Trump’s administration conveyed it.

The news release hardly stood out. It focused on the methodology of the study rather than its major findings, which showed that climate change could have a withering effect on California’s economy by inundating real estate over the next few decades.

An earlier draft of the news release, written by researchers, was sanitized by Trump administration officials, who removed references to the dire effects of climate change after delaying its release for several months, according to three federal officials who saw it. The study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, showed that California, the world’s fifth-largest economy, would face more than $100 billion in damages related to climate change and sea-level rise by the end of the century. It found that three to seven times more people and businesses than previously believed would be exposed to severe flooding.

If I had one message for coastal planners, it would be, “Don’t underestimate the risk.” Coastal storms matter, and while the extreme scenarios are attention grabbing, even a typical winter storm can add a significant amount of exposure risk on our coast.

Dr. Maya Hayden, Senior Ecologist and Coastal Adaptation Program Leader at Point Blue

“We show that for California, USA, the world’s fifth largest economy, over $150 billion of property equating to more than 6% of the state’s GDP and 600,000 people could be impacted by dynamic flooding by 2100,” the researchers wrote in the study.

The release fits a pattern of downplaying climate research at USGS and in other agencies within the administration. While USGS does not appear to be halting the pursuit of science, it has publicly communicated an incomplete account of the peer-reviewed research or omitted it under President Trump.

“It’s been made clear to us that we’re not supposed to use climate change in press releases anymore. They will not be authorized,” one federal researcher said, speaking anonymously for fear of reprisal. […]

The agency’s press release about the California coastline study was significantly altered to mask the potential impact of rising temperatures on the state’s economy. Instead, it described the methodology of the study and how it relied on “state-of-the-art computer models” and various sea-level rise predictions.

“USGS scientists and collaborators used state-of-the-art computer models to determine the coastal flooding and erosion that could result from a range of peer-reviewed, published 21st-century sea level rise and storm scenarios,” the final press release said. “The authors then translated those hazards into a range of projected economic and social exposure data to show the lives and dollars that could be at risk from climate change in California during the 21st century.”

The USGS release didn’t include the dollar figures outlined in the study.

An earlier draft of the press release, which was put online by the environmental group Point Blue Conservation Science, a participant in the study, compared the possible effect on Californians to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. The release had stark recommendations for coastal planners and emphasized that by the end of the century, a typical winter storm could threaten $100 billion in coastal real estate annually. […]

Allowing valuable information to fall through the cracks is a waste of taxpayer dollars and could prevent science from being included in policy decisions, said Joel Clement, a former climate staffer for the Department of the Interior, USGS’s parent agency. Clement, who is now a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, said the promotion of studies is an important way to get information into the hands of planners, homeowners, and policymakers. He said Interior appears to be suppressing climate science.

“It’s an insult to the science, of course, but it’s also an insult to the people who need this information and whose livelihoods and in some cases their lives depend on this,” Clement said. “What’s shocking about it is that this has been taken to a new level, where information that is essential to economic and health and safety—essentially American well-being—is essentially being shelved and being hidden.” [more]

Trump officials deleting mentions of ‘climate change’ from U.S. Geological Survey press releases

Dynamic flood modeling essential to assess the coastal impacts of climate change

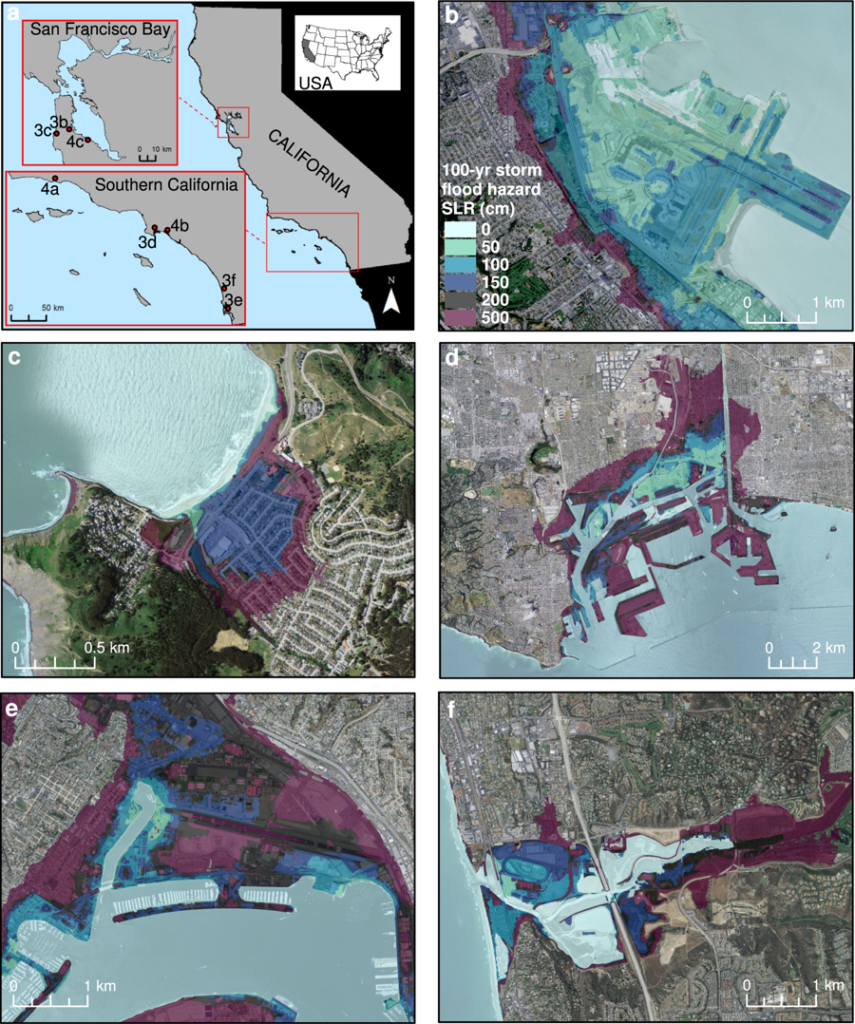

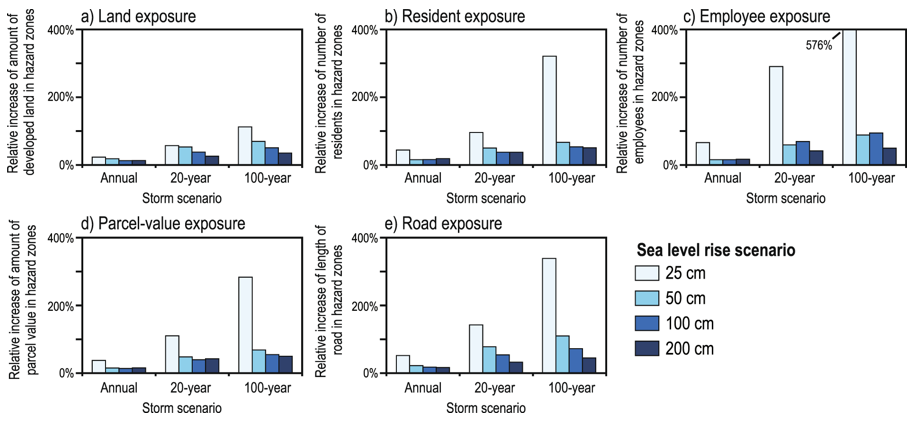

13 March 2019 (Point Blue Conservation Science) – New research from a team led by USGS and including Point Blue Conservation Science and other partners highlights how important it is to plan for the combined threats of sea level rise and coastal storms. In a paper published today in Scientific Reports (a publication of Nature Research) new modeling that combines these two threats shows a three to seven-fold increase in the projected social and economic impacts to coastal communities in California than with just sea level rise alone.

According to the study, even modest sea level rise projections of ten inches (25 centimeters) by 2040 could flood more than 150,000 residents and affect more than $30 billion in property value when combined with an extreme 100-year storm along California’s coast. Societal exposure that included storms was up to seven times greater than with sea level rise alone.

“The impact of temporary flooding from episodic storms can be really significant, especially if they are occurring with the increasing frequency that we expect,” says Dr. Maya Hayden, Senior Ecologist and Coastal Adaptation Program Leader at Point Blue. “A lot of the hazard mitigation and adaptation planning currently underway is focused on a 20-30 year time horizon and most planning is only taking sea level rise into account. This research highlights the importance of including coastal storms and high tides on top of sea level rise so that communities don’t underestimate their near-term risk.”

The research team has also taken things a step further by providing user-friendly access to the hazard maps and socioeconomic exposure results so that communities can use the information immediately for local planning. It is already being used by over 40 cities, counties, and special districts in southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area. Looking at an example of the same 100-year coastal storm scenario with 6.6 feet (2 meters) of sea level rise possible by the year 2100, the impacts increase dramatically, with as many as 600,000 people and $150 billion in property value at risk from coastal flooding – comparable to the impact of Hurricane Katrina. The study found that by the end of the century, even a typical winter storm, when combined with elevated sea levels, could threaten $100 billion of coastal real estate across the Golden State annually.

“If I had one message for coastal planners, it would be, ‘Don’t underestimate the risk,’” Dr. Hayden added. “Coastal storms matter, and while the extreme scenarios are attention grabbing, even a typical winter storm can add a significant amount of exposure risk on our coast. But our team has done more than just add another worry to people’s list. We’ve also provided tools and technical support so that planners can actually use the modeling results to make their communities more resilient.”

USGS scientists and collaborators used state-of-the-art computer models to determine the coastal flooding and erosion that could result from a range of plausible 21st-century sea level rise and storm scenarios. The authors then translated the physical hazards into economic and social exposure to show the lives and dollars that could be at risk from climate change in California during the 21st century. Their analysis focused on highly developed coastal counties in Southern California and the San Francisco Bay area, home to 95 percent of the state’s coastal population. The results are provided to the public via two web tools, one focused on physical exposure (Our Coast, Our Future [OCOF]: www.ourcoastourfuture.org) and the other on socioeconomic impacts (Hazard Exposure Reporting and Analytics [HERA]: https://www.usgs.gov/apps/hera/).

Most climate change projections forecast 10 inches (25 cm) of sea level rise in California within 30 years. At every high tide, the research showed, this could mean flooded areas where 37,000 people live and 13,000 people work, affecting $8 billion in property value. Add a 100-year coastal storm, which has a 1 percent chance of happening every year, and the study showed that the numbers jump to 155,000 residents, 86,000 employees and $32 billion of coastal at-risk real estate. Emergency managers and others often use 100-year storms for planning purposes.

The new paper was published on March 13th in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports

(http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40742-z). “Dynamic flood modeling essential to assess the coastal impacts of climate change” included research by scientists from the USGS, Coastal Carolina University, Deltares, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Point Blue Conservation Science.

About Point Blue Conservation Science

Point Blue advances conservation of birds, other wildlife and ecosystems through science, partnerships, and outreach. Our highest priority is to reduce the impacts of habitat loss, climate change, and other environmental threats while promoting nature-based solutions for wildlife and people, on land and at sea. Visit Point Blue at www.pointblue.org.

Contact

- Zach Warnow, Director of Communications, (415) 786-5285, zwarnow@pointblue.org

- Maya Hayden, Ph.D., Senior Ecologist and Coastal Adaptation Program Leader, (707) 7812555, ext. 373, mhayden@pointblue.org

ABSTRACT: Coastal inundation due to sea level rise (SLR) is projected to displace hundreds of millions of people worldwide over the next century, creating significant economic, humanitarian, and national-security challenges. However, the majority of previous efforts to characterize potential coastal impacts of climate change have focused primarily on long-term SLR with a static tide level, and have not comprehensively accounted for dynamic physical drivers such as tidal non-linearity, storms, short-term climate variability, erosion response and consequent flooding responses. Here we present a dynamic modeling approach that estimates climate-driven changes in flood-hazard exposure by integrating the effects of SLR, tides, waves, storms, and coastal change (i.e. beach erosion and cliff retreat). We show that for California, USA, the world’s 5th largest economy, over $150 billion of property equating to more than 6% of the state’s GDP and 600,000 people could be impacted by dynamic flooding by 2100; a three-fold increase in exposed population than if only SLR and a static coastline are considered. The potential for underestimating societal exposure to coastal flooding is greater for smaller SLR scenarios, up to a seven-fold increase in exposed population and economic interests when considering storm conditions in addition to SLR. These results highlight the importance of including climate-change driven dynamic coastal processes and impacts in both short-term hazard mitigation and long-term adaptation planning.

Dynamic flood modeling essential to assess the coastal impacts of climate change