Occurrence of back-to-back heat waves likely to accelerate with global warming – “Compound heat waves are projected to grow more rapidly than simple heat waves”

By Joseph Albanese

8 May 2019

(Princeton Environmental Institute) – As the planet continues to warm, multi-day heat waves are projected to increase in frequency, length and intensity. The additive effects of these extreme heat events overwhelm emergency service providers and hospital staff with heat-related maladies, disrupt the electrical grid and can even cause delays in air travel.

But existing studies do not consider the increased loss of life and economic hardship that could come from back-to-back — or compound — heat waves, which bring cycles of sweltering temperatures with only brief periods of normal conditions in between.

Princeton University researchers affiliated with the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI) now have provided the first estimation of the potential damage wrought by sequential heat waves, according to a paper published 12 April 2019 in the journal Earth’s Future. The authors used computer simulations of Earth’s climate to find that compound heat events will increase as global warming continues and will pose greater risks to public health and safety.

Compound heat waves would be especially dangerous to people who are already vulnerable to heat waves, particularly the elderly and residents of low-income areas. Government warning systems and health care outreach do not currently calculate the escalating risk these populations face from several heat waves in a row, the researchers reported. Instead, risk and response are determined by the severity of each individual episode of extreme temperatures.

Some of the deadliest heat waves on record featured fluctuating temperatures rather than single stretches of searing heat, said first author Jane Baldwin, a postdoctoral researcher in the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI) who also is supported by the High Meadows Foundation through the Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment (C-PREE) in Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

“Averaged over time, heat waves are the most deadly type of natural disaster in the United States, in addition to causing many emergency room visits, lost working hours and lower agricultural yields,” Baldwin said. Heat waves and the droughts that can accompany them are responsible for approximately 20% of the mortalities associated with natural hazards in the continental United States.

“However, if you look at the deadliest heat waves in Europe and the United States, many have more unusual temporal structures with temperature jumping above and below extremely hot levels multiple times,” Baldwin said. Because of the shorter recovery period between events, the effects of these compound heat waves are often significantly worse than stand-alone events.

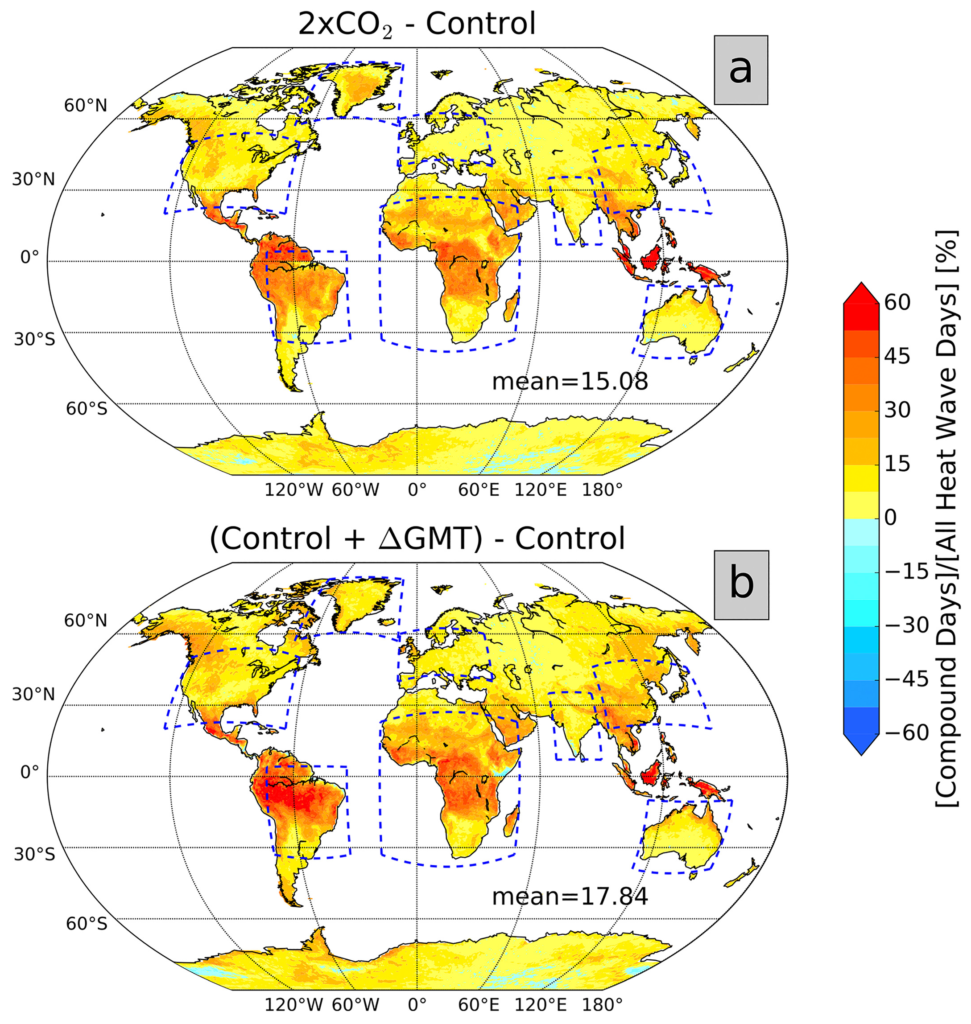

Co-author Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute, said that, adding to the urgency, is the fact that “compound heat waves are projected to grow more rapidly than simple heat waves.”

“Our work begins exploring the implications of compound heat waves if climate change continues unchecked,” Oppenheimer said. “We want to know how the effects of compound heat waves will differ from — and amplify — the already severe consequences for human health, infrastructure stability and crop yield that we see from single-event heat waves.”

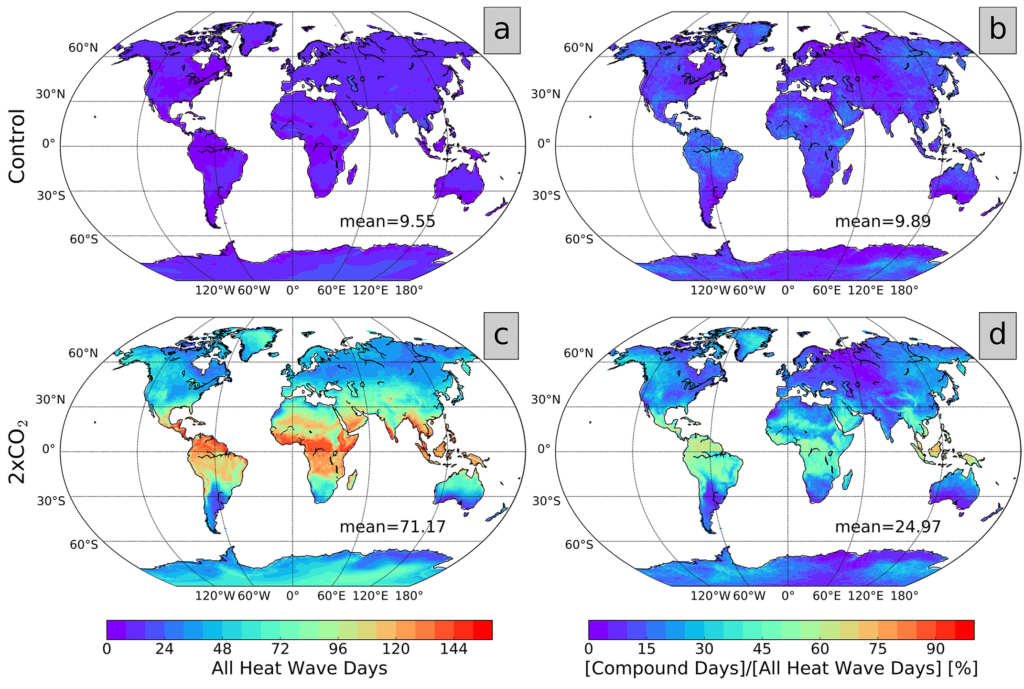

The researchers ran climate simulations on an advanced model partly designed by co-author Gabriel Vecchi, professor of geosciences and the Princeton Environmental Institute, in conjunction with the National Oceanographic and Atmosphere Administration’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory located on Princeton’s Forrestal Campus. They found that as global temperatures increase, heat waves will become more frequent and the time between them will become shorter.

One heat wave after another will leave emergency service providers and infrastructure-repair crews with less time to recover from the past event before being confronted by new heat waves, Baldwin said. Additionally, those housed in buildings lacking climate control systems will be subjected to even greater periods of heat, as structures tend to retain heat. Citing a recent study, Baldwin noted that “surveys of low-income housing in places such as Harlem have found that after a heat wave has ended, temperatures indoors can remain elevated for a number of days.”

Policymakers and crisis managers will increasingly need to look back to recent events when preparing for future heat waves, as the ramifications may be felt well after the mercury has dropped, the researchers reported. Current heat wave warning systems that are configured to look toward future events might be recalibrated to take preceding heat events into account as well. Failing to account for the added vulnerability created by the cascading effects of compound heat waves may lead to a greater loss of life as global warming continues.

“Ultimately, with more flexible temporal structures in heat-wave warning systems, we think that heat wave impacts might be reduced and more lives might be saved,” Baldwin said. “[T]o facilitate adaptation and policy response, more work is needed to quantify the impacts of these compound heat waves.”

Baldwin points out that the study in Earth’s Future is an imperative first step in understanding the sprawling effects of compound heat waves. The paper is likely to spawn new work. For the next step, the researchers are working to understand in more detail the health risks posed by compound heat waves.

The paper, “Temporally Compound Heat Wave Events and Global Warming: An Emerging Hazard,” was published 12 April 2019 in Earth’s Future. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE 1148900), the PEI-STEP Graduate Fellowship program, the PEI Carbon Mitigation Initiative, and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association’s Climate Program Office.

Occurrence of back-to-back heat waves likely to accelerate with climate change

ABSTRACT: The temporal structure of heat waves having substantial human impact varies widely, with many featuring a compound structure of hot days interspersed with cooler breaks. In contrast, many heat wave definitions employed by meteorologists include a continuous threshold‐exceedance duration criterion. This study examines the hazard of these diverse sequences of extreme heat in the present, and their change with global warming. We define compound heat waves to include those periods with additional hot days following short breaks in heat wave duration. We apply these definitions to analyze daily temperature data from observations, NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory global climate model simulations of the past and projected climate, and synthetically generated time series. We demonstrate that compound heat waves will constitute a greater proportion of heat wave hazard as the climate warms and suggest an explanation for this phenomenon. This result implies that in order to limit heat‐related mortality and morbidity with global warming, there is a need to consider added vulnerability caused by the compounding of heat waves.

SIGNIFICANCE: Heat waves are multiday periods of extremely hot temperatures and among the most deadly natural disasters. Studies show that heat waves will become longer, more numerous, and more intense with global warming. However, these studies do not consider the implications of multiple heat waves occurring in sequence, or “compounding.” In this study, we analyze physics‐based simulations of Earth’s climate and temperature observations to provide the first quantifications of hazard from compound heat waves. We demonstrate that compound events will constitute a greater proportion of heat wave risk with global warming. This has important policy implications, suggesting that vulnerability from prior heat waves will be increasingly important to consider in assessing heat wave risk and that heat wave warning systems that currently primarily consider future‐predicted weather should also account for the recent history of weather.

Temporally Compound Heat Wave Events and Global Warming: An Emerging Hazard