Water increasingly at the center of conflicts from Ukraine to the Middle East – “It’s very disturbing that in particular attacks on civilian water infrastructure seem to be on the rise”

By Ian James

28 December 2023

(Los Angeles Times) – Six months ago, an explosion ripped apart Kakhovka Dam in Ukraine, unleashing floods that killed 58 people, devastated the landscape along the Dnipro River and cut off water to productive farmland.

The destruction of the dam — which Ukrainian officials and the European Parliament blame on Russia, even though the structure was under Russian control — was one in a series of attacks on water infrastructure that have occurred during the Russia-Ukraine war.

Alongside those strikes, violence linked to water has erupted this year in other areas around the world.

In countries including India, Kenya and Yemen, disputes over water have triggered bloodshed.

And on the Iran-Afghanistan border, a conflict centering on water from the Helmand River boiled over in deadly clashes between the two countries’ forces.

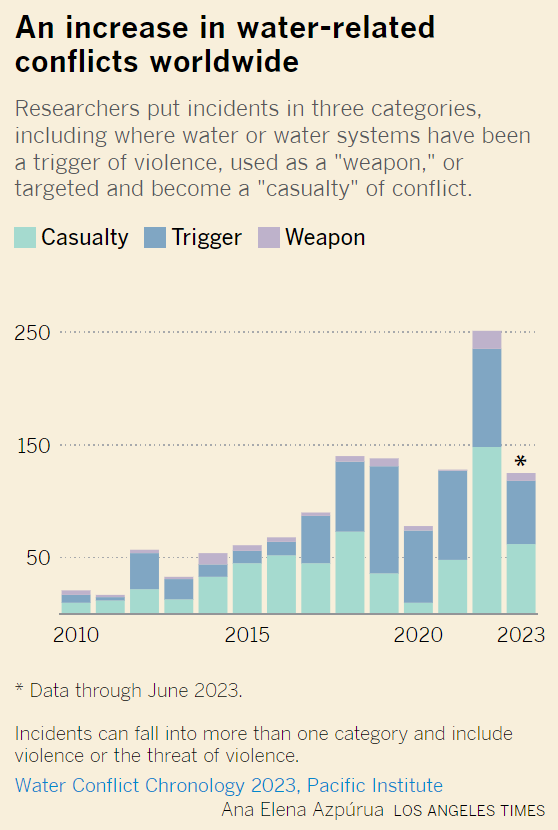

These are some of the 344 instances of water-related conflicts worldwide during 2022 and the first half of 2023, according to data compiled by researchers at the Pacific Institute, a global water think tank. Their newly updated data, collected through an effort called the Water Conflict Chronology, shows a major upsurge in violent incidents, driven partly by the targeting of dams and water systems in Ukraine as well as an increase in water-related violence in the Middle East and other regions.

“It’s very disturbing that in particular attacks on civilian water infrastructure seem to be on the rise,” said Peter Gleick, the Pacific Institute’s co-founder and senior fellow. “We also see a worrying increase in violence associated with water scarcity worsened by drought, climate disruptions, growing populations, and competition for water.”

Gleick has been tracking cases of water-related conflict for more than three decades and cataloged the latest incidents with other researchers at the Oakland-based institute.

The database now lists more than 1,630 conflicts. Most of the cases have occurred since 2000, and there has been a rising trend over the last decade, with a spike the last few years.

The researchers collect data from news reports and other sources and accounts. They classify instances into three categories: where water or water systems have been a trigger of violence, used as a “weapon” or have been targeted and become a “casualty” of violence. […]

In the West Bank, incidents involving the destruction of orchards, irrigation systems and water tanks have been happening for years, “but it picked up a lot in the last two years,” said Morgan Shimabuku, a senior researcher at the Pacific Institute.

Elsewhere in the Middle East, there have been deadly fights over control of water sources in Yemen, bombings of water infrastructure in Syria, and clashes during protests over lack of water in Iraq.

Shimabuku said efforts to ease conflicts will require “protecting civilian water infrastructure and resources and developing water-governance structures that are just and equitable.”

Different patterns of violence have emerged in other regions. In Latin America, hundreds of environmental activists have been killed in recent years, including many Indigenous activists.

In one of the most infamous cases, Honduran Indigenous activist Berta Cáceres was shot and killed in 2016 after years of threats over her work to stop a dam project on the Gualcarque River.

There have been many more killings in the last few years. Those listed in the database include the assassinations of a Honduran activist who protested an open-pit mine in 2020, a Honduran activist who was fighting a new dam on the Ulua River in 2021, and an activist in Cuernavaca, Mexico, who had led protests over inadequate water service.

In various cases, Shimabuku said, Indigenous people have been involved in violent conflicts over water and land protection where “government-backed corporate entities are committing violence.”

“A lot of those are people protecting water, because they don’t want a dam built, they don’t want their forests to be destroyed, and their rivers to be destroyed,” Shimabuku said. [more]

Water increasingly at the center of conflicts from Ukraine to the Middle East