“Super meth” and other drugs push U.S. crisis beyond opioids – “It’s no longer an opioid epidemic. This is an addiction crisis.”

By Jan Hoffman

13 November 2023

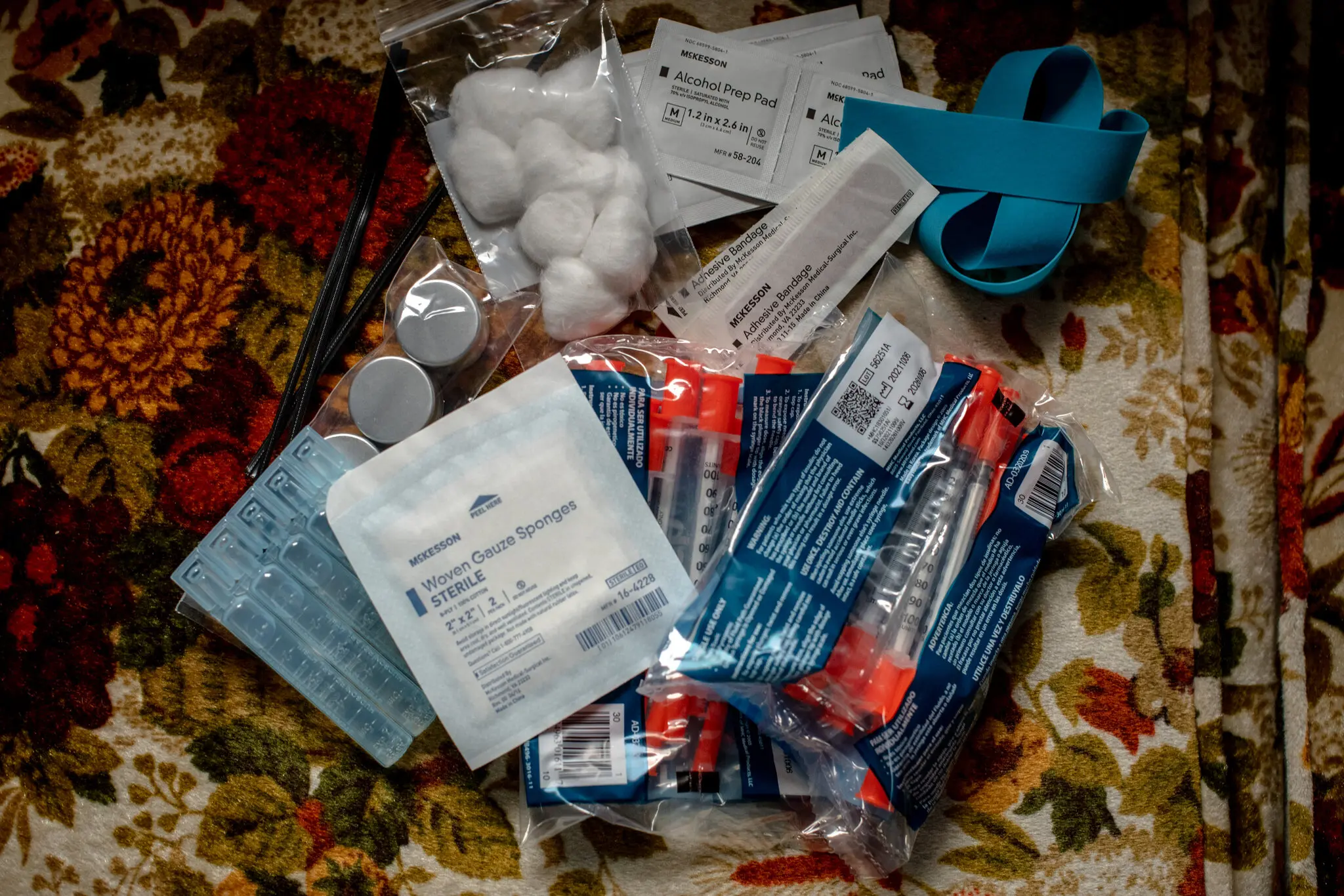

(The New York Times) – Dr. Nic Helmstetter crab-walked down a steep, rain-slicked trail into a grove of maple and cottonwood trees to his destination: a dozen tents in a clearing by the Kalamazoo River, surrounded by the detritus of lives perpetually on the move. Discarded red plastic cups. A wet sock flung over a bush. A carpet square. And scattered across the forest floor: orange vial caps and used syringes.

Kalamazoo, a small city in Western Michigan, is a way station along the drug trafficking corridor between Chicago and Detroit. In its parks, under railroad overpasses and here in the woods, people ensnared by drugs scramble to survive. Dr. Helmstetter, who makes weekly primary care rounds with a program called Street Medicine Kalamazoo, carried medications to reverse overdoses, blunt cravings and ease withdrawal-induced nausea.

But increasingly, the utility of these therapies, developed to address the decades-old opioid crisis, is diminishing. They work to counteract the most devastating effects of fentanyl and heroin, but most users now routinely test positive for other substances too, predominantly stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine, for which there are no approved medications.

Rachel, 35, her hair dyed a silvery lavender, ran to greet Dr. Helmstetter. She takes the medicine buprenorphine, which acts to dull her body’s yearning for opioids, but she was not ready to let go of meth.

“I prefer both, actually,” she said. “I like to be up and down at the same time.”

The United States is in a new and perilous period in its battle against illicit drugs. The scourge is not only opioids, such as fentanyl, but a rapidly growing practice that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention labels “polysubstance use.”

Over the last three years, studies of people addicted to opioids (a population estimated to be in the millions) have consistently shown that between 70 and 80 percent also take other illicit substances, a shift that is stymieing treatment efforts and confounding state, local and federal policies.

“It’s no longer an opioid epidemic,” said Dr. Cara Poland, an associate professor at the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine. “This is an addiction crisis.”

The non-opioid drugs include those relatively new to the street, like the animal tranquilizer xylazine, which can char human flesh, anti-anxiety medications like Valium and Klonopin and older recreational stimulants like cocaine and meth. Dealers sell these drugs, plus counterfeit Percocet and Xanax pills, often mixed with fentanyl.

The incursion of meth has been particularly problematic. Not only is there is no approved medical treatment for meth addiction, but meth can also undercut the effectiveness of opioid addiction therapies. Meth explodes the pleasure receptors, but also induces paranoia and hallucinations, works like a slow acid on teeth and heart valves and can inflict long-lasting brain changes.

The Biden administration has been pouring billions into opioid interventions and policing traffickers but has otherwise lagged in keeping pace with the evolution of drug use. There has been comparatively little discussion about meth and cocaine, despite the fact that during the 12-month period ending in May 2023, over 34,000 deaths were attributed to methamphetamine and 28,000 to cocaine, according to provisional federal data.

Just last month, the Food and Drug Administration issued draft guidelines for the development of therapies for stimulant-use disorders “critically needed to address treatment gaps.”

In the Street Medicine van up the road from the tents, Dr. Sravani Alluri, the program’s director and a family medicine physician, gave Rachel an injection of antipsychotic medicine and then sorted through lab results showing the chilling omnipresence of numerous substances.

- Patient No. 1: positive for fentanyl, methamphetamine and xylazine.

- Patient No. 2: positive for amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, THC and gabapentin, a prescription painkiller whose misuse is on the rise.

- Patient No. 3: positive for fentanyl, methamphetamine, THC and xylazine.

The spread of super meth

“Treating someone for opiates is relatively easy,” said Dr. Paul Trowbridge, the addiction medicine specialist at the Trinity Health Recovery Medicine clinic in Grand Rapids, an hour north of Kalamazoo. That’s largely because of buprenorphine and methadone, federally approved medications with years of evidence attesting to their effectiveness in subduing opioid cravings, and Narcan, an over-the-counter nasal spray that reverses opioid overdoses.

But meth, he said, “is a monster.”

His patients typically have either Medicaid or private health insurance and a roof over their heads, even if it’s a shelter. Many have steady jobs — dental hygienists, construction workers, tech sales people.

Still, the challenges of helping them are daunting.

Their use of multiple drugs is not always voluntary. Dealers can be sloppy, Dr. Trowbridge said, or intentionally salt one drug with another, to bind customers to the new mix.

“It’s really unpredictable what people are buying, which makes it so dangerous for them,” he said. “It’s a killing field out there.”

Some opioid users seek the fireworks of meth and other stimulants to offset the warm, sleepy embrace of opioids. Some use meth to stay awake to ward off thieves and rapists.

Medications like methadone can safely replace more destructive opioids and satiate the brain’s opioid receptors. But subduing the urge for stimulants, which set off the release of stratospheric levels of the brain chemicals dopamine and serotonin, is more complex, involving many unknowns. And Narcan, which has saved at least hundreds of thousands who overdosed on opioids, has no effect on stimulants.

Moreover, depending on whether the user routinely turns to cocaine, meth or prescription amphetamine, side effects, responses and behavior patterns vary greatly.

“The truth is, we really don’t have a good answer at this point as to why it’s so challenging to develop these treatments,” said Marta Sokolowska, the deputy director for substance use and behavioral health at the F.D.A.’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

Last year, according to preliminary federal data, stimulants were present in 42 percent of overdose deaths that involved opioids.

Like opioids, which originally came from the poppy, meth started out as a plant-based product, derived from the herb ephedra. Now, both drugs can be produced in bulk synthetically and cheaply. They each pack a potentially lethal, addictive wallop far stronger than their precursors.

In recent decades, opioids grew so dominant that meth and its stimulant cousins proliferated in the shadows.

A decade or so ago, Mexican drug lords figured out how to mass-produce a synthetic “super meth.” It has provoked what some researchers are calling a second meth epidemic.

Popular up and down the West Coast, super meth from Mexican and American labs has been marching East and South and into parts of the Midwest, including Grand Rapids and Kalamazoo. [more]