Factory fishing in Antarctica for krill targets the cornerstone of a fragile ecosystem – “What’s coming out of the side are the remnants of the ecosystem”

By Joshua Goodman and David Keyton

13 October 2023

(AP) – The Antarctic Endeavour glides across the water’s silky surface as dozens of fin whales spray rainbows from their blowholes into a fairy tale icescape of massive glaciers.

But as a patrol of environmentalists approaches the Chilean super trawler in an inflatable boat, the cruder realities of modern industrial fishing come into view.

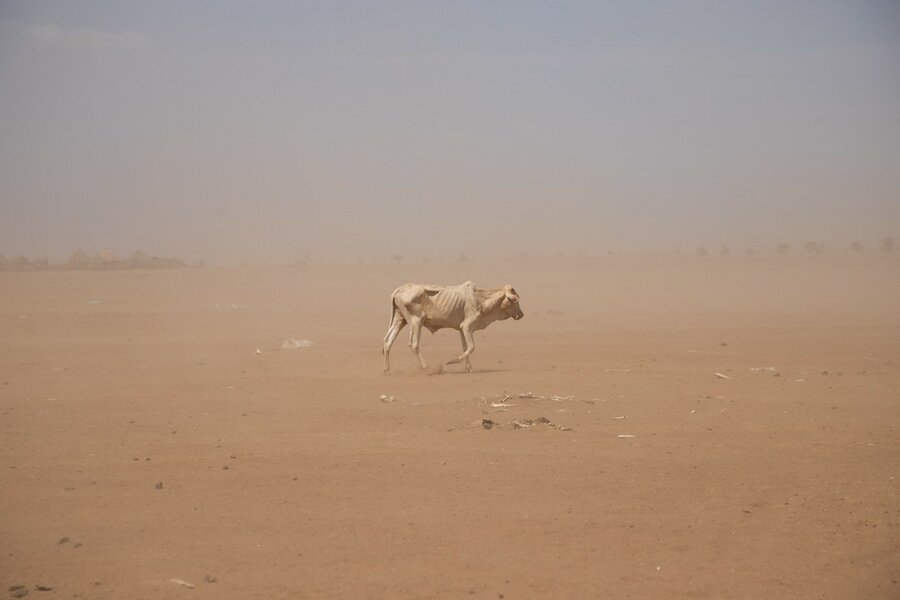

From one of the ship’s drain holes, a steaming pink sludge cascades into the frigid waters of the Southern Ocean. It’s the foul-smelling runoff from processing the 80-meter (260-foot) factory ship’s valuable catch: Antarctic krill, a paper-clip-sized crustacean central to the region’s food web and, scientists say, an important buffer to global warming.

“What’s coming out of the side are the remnants of the ecosystem,” says Alistair Allan, an activist for Australia’s Bob Brown Foundation, as he looks on from the inflatable boat. “If this was off the coast of Alaska, it would be a national park. But since it’s down here at the bottom of the world, where no one is watching, you have ships almost running into whales feeding on the same things they’re fishing.”

While krill fishing is banned in U.S. waters due to concerns it could impact whales, seals and other animals that feed on the shrimp-like creatures, it’s been taking place for decades in Antarctica, where krill are most abundant. It started in the 1960s, when the Soviet Union launched an industrial fleet of trawlers in search of an untapped protein source that could be canned like sardines.

Surging demand for nutrient-rich krill — for feeding farm-raised fish, omega-3 pills, pet food and protein shakes — combined with advances in fishing and the still unknown impact from climate change has some scientists warning the fishery is at a critical juncture and in urgent need of stricter controls. But any further action is mired in geopolitical wrangling as Russia and China look to quickly expand the catch.

Two Associated Press journalists spent more than two weeks at sea in March, at the tail end of the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, aboard the Dutch-flagged Allankay, operated by the conservation group Sea Shepherd Global, to take a rare, up-close look at the world’s southernmost fishery.

Starting every December, around 10 to 12 mostly Norwegian and Chinese vessels brave the rough seas whipping across the tip of South America to descend upon the South Orkney Islands, a desolate chain of rocky outcrops. From there, as temperatures warm, the fleet follows the massive swarms of krill toward the South Pole, fishing at the foundation of the fragile ecosystem’s food web.

Under a conservation agreement developed almost two decades ago, the krill catch has soared: from 104,728 metric tons in 2007 to 415,508 metric tons in 2022, as larger, more sophisticated vessels have joined the chase. Those levels were below internationally agreed conservation limits.

A U.S.-led coalition has been calling for more restrictions and marine reserves as krill’s vital role as food for other species and in removing large amounts of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere comes into focus. But it has met stiff opposition from China and Russia, which have made no secret of their geopolitical ambitions in the white continent.

Direct competition with marine mammals seems inevitable — a reality dramatically underscored when four juvenile humpback whales were entangled by a Norwegian krill boat in 2021 and 2022.

While the end of commercial whaling has allowed populations to rebound, a new study by the University of California, Santa Cruz found that pregnancy rates among humpback whales in Antarctica have been falling sharply — possibly due to a lack of krill, their main prey. Chinstrap penguins and fur seals face similar stresses. [more]

Factory fishing in Antarctica for krill targets the cornerstone of a fragile ecosystem