New York City area gets one of its wettest days in decades, as rain floods subways and streets – “The sad reality is that our climate is changing faster than our infrastructure can respond”

By Jake Offenhartz, Jennifer Peltz, and Bobby Caina Calvan

29 September 2023

NEW YORK (AP) – Rain walloped the New York metropolitan area with a startling punch Friday, knocking out several subway and commuter rail lines, stranding drivers on highways, flooding basements and shuttering a terminal at LaGuardia Airport for hours in one of the city’s wettest days in decades.

More than 7.25 inches (18.41 centimeters) of rain had fallen in parts of Brooklyn by nightfall, with at least one spot seeing 2.5 inches (6 centimeters) in a single hour, according to weather and city officials. The 8.65 inches (21.97 centimeters) at John F. Kennedy Airport surpassed its record for any September day, a bar set during Hurricane Donna in 1960, the National Weather Service said.

And more downpours were expected.

That’s not a pattern New York City is accustomed to. That’s a pattern that Miami might be accustomed to, maybe Singapore.

Rohit Aggarwala, New York City’s environmental-protection commissioner

The deluge came two years after the remnants of Hurricane Ida dumped record-breaking rain on the Northeast and killed at least 13 people in New York City, mostly in flooded basement apartments. Although no deaths or severe injuries have been reported so far from Friday’s storm, it stirred frightening memories.

Ida killed three of Joy Wong’s neighbors, including a toddler. And on Friday, water began lapping against the front door of her building in Woodside, Queens.

“I was so worried,” she said. It became too dangerous to leave: “Outside was like a lake, like an ocean.”

Within minutes, water filled the building’s basement nearly to the ceiling. After the family’s deaths in 2021, the basement was turned into a recreation room. It is now destroyed.

City officials said they got reports of six flooded basement apartments Friday, but all occupants got out safely.

Gov. Kathy Hochul and Mayor Eric Adams declared states of emergency and urged people to stay put if possible. But schools were open, students went to class and many adults went to work, only to wonder how they would get home.

Virtually every subway line was at least partly suspended, rerouted or running with delays. Metro-North commuter rail service from Manhattan was suspended for much of the day but began resuming by evening. The Long Island Rail Road was snarled, 44 of the city’s 3,500 buses got stranded and bus service was disrupted citywide, transit officials said.

“When it stops the buses, you know it’s bad,” Brooklyn high school student Malachi Clark said after trying to get home by bus, then subway. School buses were running, but they transport only a fraction of public school students, many of them disabled.

A long line of people snaked from the ticket counter in the afternoon at Grand Central Terminal, where Mike Tags was among those whose trains had been canceled. Railroad employees had suggested possible workarounds, but he wondered whether they would work out.

“So I’m going to sit here, ride it out, until they open up,” he said.

Traffic hit a standstill earlier in the day on a stretch of the FDR Drive, a major artery along Manhattan’s east side. With water above cars’ tires, some drivers abandoned their vehicles.

At around 11 a.m., Priscilla Fontallio said she had spent three hours in her car, which was on a piece of the highway that wasn’t flooded but wasn’t moving.

“Never seen anything like this in my life,” she said.

On a street in Brooklyn’s South Williamsburg neighborhood, workers were up to their knees in water as they tried to unclog a storm drain while cardboard and other debris floated by. Some people arranged milk crates and wooden boards to cross flooded sidewalks.

Flights into LaGuardia were briefly halted in the morning, and then delayed, because of water in the refueling area. Flooding also forced the closure of one of the airport’s three terminals for several hours. Terminal A resumed normal operations around 8 p.m.

A Brooklyn school was evacuated because its boiler was smoking, possibly because water got into it, Schools Chancellor David Banks said at a news briefing. Another Brooklyn school was mopping up ground-floor classrooms, City Councilwoman Crystal Hudson said in an email seeking volunteers to help.

The New York Rangers and New York Islanders postponed a preseason game on Long Island. And at the waterlogged Central Park Zoo, a sea lion swam out of her swollen pool. With the zoo closed because of the weather, she looked around for a bit before returning to the pool, zoo officials said in a statement.

In Brooklyn’s Crown Heights, Jessie Lawrence awoke to the sound of rain dripping from the ceiling of her fourth-floor apartment and heard strange sounds outside her front door.

She opened it to find “the water was coming in thicker and louder,” pouring into the hallway and flowing down the stairs, she said. Rain had pooled on the roof and was leaking through a skylight.

Hoboken, New Jersey, and other cities and towns around New York City also experienced flooding. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy called for state offices to close at 3 p.m., except for essential personnel.

Why so much rain? The remnants of Tropical Storm Ophelia over the Atlantic Ocean combined with a mid-latitude system arriving from the west, at a time of year when conditions coming off the ocean are particularly juicy for storms, National Weather Service meteorologist Ross Dickman said. And this combination storm parked itself over New York for 12 hours.

The weather service had warned of 3 to 5 inches (7.5 to 13 centimeters) of rain and told emergency managers to expect over 6 inches (15 centimeters) in some places, Dickman said.

The deluge came less than three months after a storm caused deadly floods in New York’s Hudson Valley and swamped Vermont’s capital, Montpelier.

As the planet warms, storms are forming in a hotter atmosphere that can hold more moisture, making extreme rainfall more frequent, according to atmospheric scientists.

But in the case of Friday’s storm, nearby ocean temperatures were below normal, and air temperatures weren’t too hot. Still, it became the third time in two years that rain fell at rates near 2 inches (5 centimeters) an hour in Central Park, which is unusual, Columbia University climate scientist Adam Sobel said.

The park recorded 5.8 inches (14.73 centimeters) of rain by nightfall Friday.

New York City area gets one of its wettest days in decades, as rain swamps subways and streets

New York City Is Not Built for This

By Nancy Walecki

29 September 2023

(The Atlantic) – New York City’s sewer system is built for the rain of the past—when a notable storm might have meant 1.75 inches of water an hour.

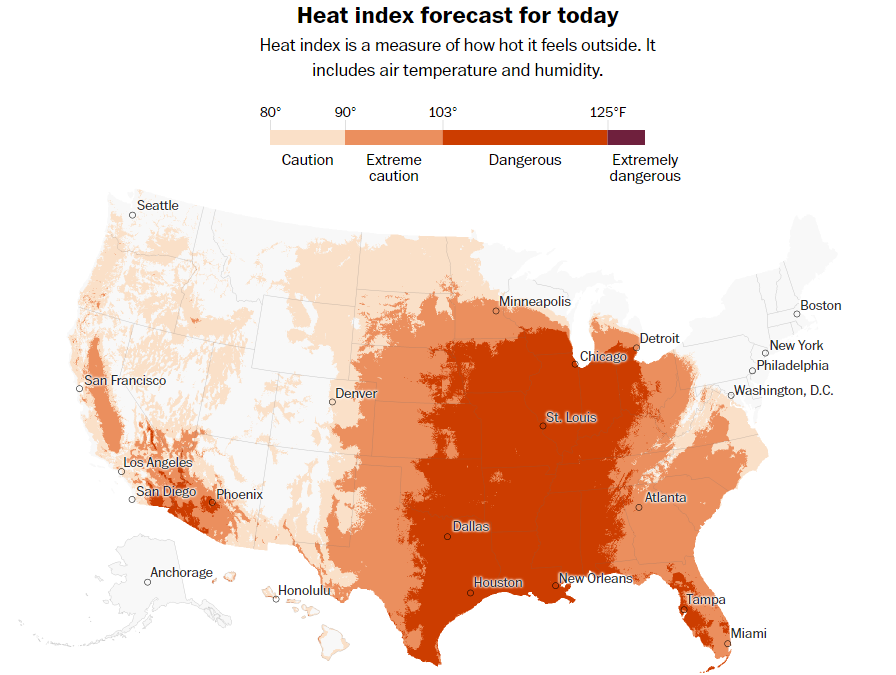

It wasn’t built to handle the rainfall from Hurricane Irene, Hurricane Sandy, or, more recently, Hurricane Ida—which dumped 3.15 inches an hour on Central Park. And it wasn’t built to handle the kind of extreme rainfall that is becoming routine: The city flooded last December, last April, and last July—an unusual seasonal span. “We now have in New York something much more like a tropical-rainfall pattern,” Rohit Aggarwala, New York City’s environmental-protection commissioner, said yesterday at The Atlantic Festival. “And it happens over and over again.”

It happened today. Less than 24 hours after Aggarwala’s statements, rain arrived in New York City—the kind that sends waterfalls through Brooklyn subway ceilings, dangerously floods basements, and floats cars on the road like rubber ducks. Mayor Eric Adams said earlier today that the city could receive up to eight inches of rain today; parts of Brooklyn saw a month’s worth of rain in just three hours. New York State Governor Kathy Hochul has declared a state of emergency, and New York City residents received emergency alerts cautioning them to avoid travel (unless, ominously, they were evacuating), seek high ground, and avoid driving.

“You always build to the record” when designing infrastructure, Aggarwala said yesterday. The problem comes when the changing climate creates conditions that blow through those records. He also said the 1.75-inches-an-hour standard isn’t met across the board. “That’s our target—not everywhere in the city is up to that standard.” And since Hurricane Ida hit two years ago, there have been at least half a dozen instances in which certain neighborhoods have received two inches or more of rainfall an hour, he said. “That’s not a pattern New York City is accustomed to. That’s a pattern that Miami might be accustomed to, maybe Singapore.”

Already, today’s rainfall, as measured in Central Park, is the worst the city has seen since Ida, Zachary Iscol, the New York City emergency-management commissioner, confirmed at a press conference today. (Ultimately, Ida dropped 7.2 inches of rain on Central Park and nearly six inches on Prospect Park.) The city’s sewers simply can’t process water that quickly. “The sad reality is that our climate is changing faster than our infrastructure can respond,” Aggarwala said at the same conference.

Extreme rainfall isn’t just a New York City problem. A recent analysis found that one in nine residents in the contiguous United States is at significant risk of storms that will bring at least 50 percent more water than their local infrastructure can handle—overwhelming the pipes, channels, and culverts that might have met the rainfall records of the past. Any place trying to fix this mismatch might not have the basic information it needs, either: The periodic update of national rainfall from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, for instance, won’t arrive for another three to four years, which could keep climate-resilience efforts lagging behind the speed at which the climate is changing.

As acute and random as these events can feel, Aggarwala warned yesterday against myopia. “We can’t say, ‘Well, this is a one-off and maybe it won’t happen again,’” he said. “This is our new reality.”