Get ready for tens of millions of climate refugees

By Susan Cosier

24 April 2019

(Technology Review) – In 2006, the British economist Nicholas Stern warned that one of the biggest dangers of climate change would be mass migration. “Climate-related shocks have sparked violent conflict in the past,” he wrote, “and conflict is a serious risk in areas such as West Africa, the Nile Basin, and Central Asia.”

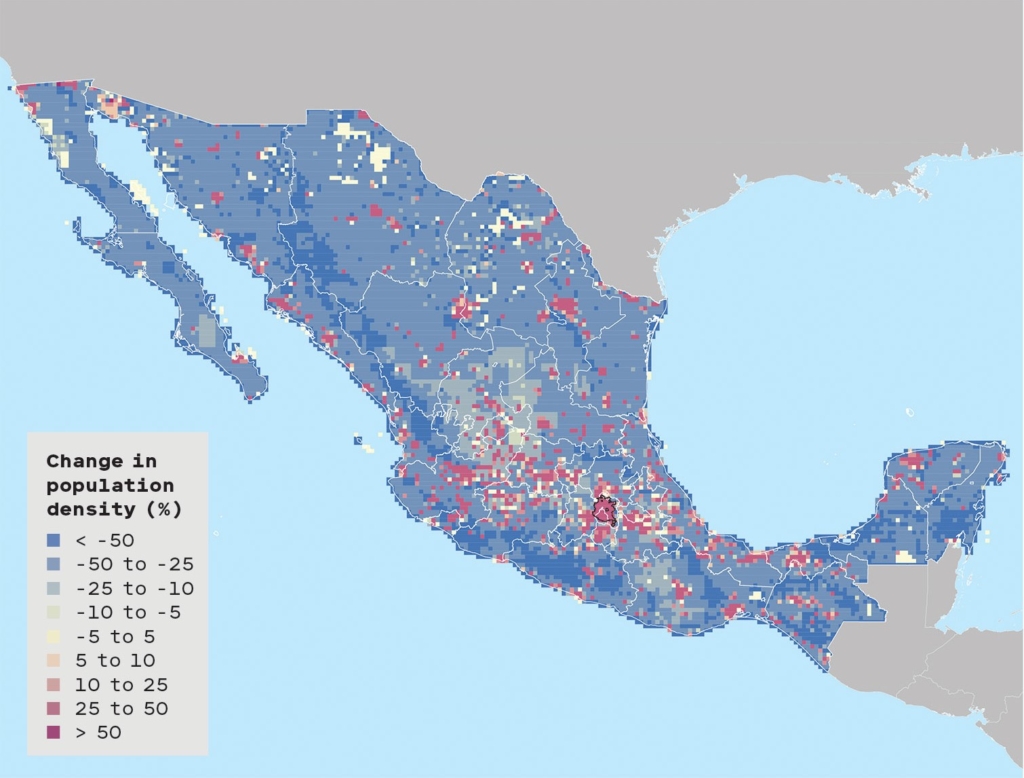

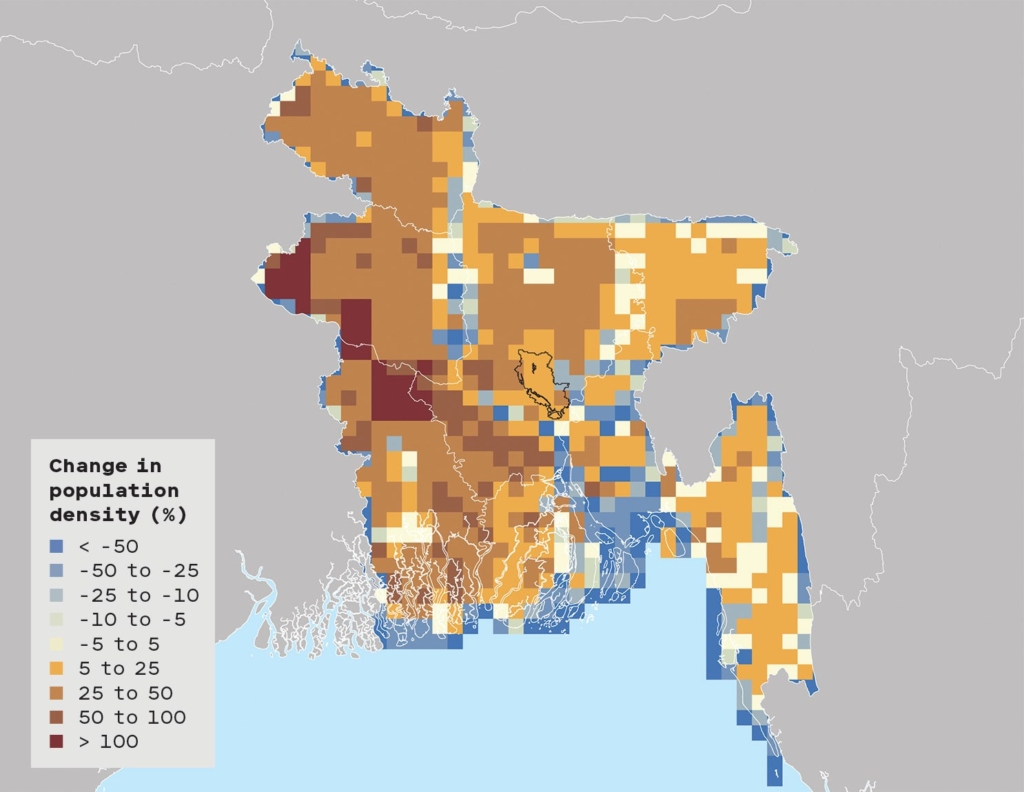

More than a decade later we’re still trying to create models that might tell us where people might move, and when. Last year a report for the World Bank, the first to model migration due to climate change on a large scale, estimated that as many as 143 million people in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America could have to relocate within their countries by 2050.

But is that a number we can trust? Modelers make many assumptions, like whether people will react the same way as they did to earlier climate disasters. Although models are improving, predicting how high seas will rise and how long droughts could last involves many unknowns. “There’s still a lot of work to do in this field, and I think we’re just scratching the surface,” says Bryan Jones of Baruch College, one of the report’s authors.

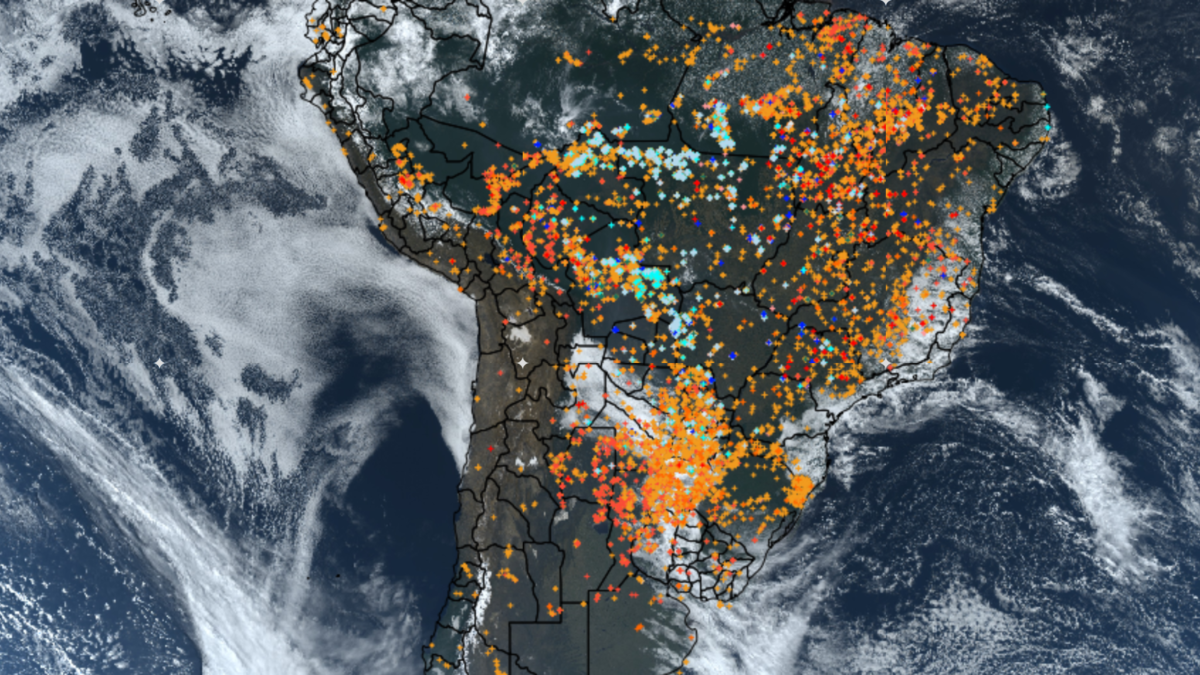

Modelers are trying to get more accurate numbers with new information from satellite images or mobile-phone data. But there are “constraints in using that technology,” says Valerie Mueller, an economist at Arizona State University and author of a number of studies on climate-change-induced migration. For example, satellite imagery can be used to count populations, but changes in population could result from births and deaths, not just migration. SIM cards in mobile phones can show where the phone went, but not why; and more than one person might use any given phone. [more]