Solar sprawl is tearing up the Mojave Desert. Is there a better way?

By Sammy Roth

27 June 2023

(Los Angeles Times) – High above the Las Vegas Strip, solar panels blanketed the roof of Mandalay Bay Convention Center — 26,000 of them, rippling across an area larger than 20 football fields.

From this vantage point, the sun-dappled Mandalay Bay and Delano hotels dominated the horizon, emerging like comically large golden scepters from the glittering black panels. Snow-tipped mountains rose to the west.

It was a cold winter morning in the Mojave Desert. But there was plenty of sunlight to supply the solar array.

“This is really an ideal location,” said Michael Gulich, vice president of sustainability at MGM Resorts International.

The same goes for the rest of Las Vegas and its sprawling suburbs.

Sin City already has more solar panels per person than any major U.S. metropolis outside Hawaii, according to one analysis. And the city is bursting with single-family homes, warehouses and parking lots untouched by solar.

There’s enormous opportunity to lower household utility bills and cut climate pollution — without damaging wildlife habitat or disrupting treasured landscapes.

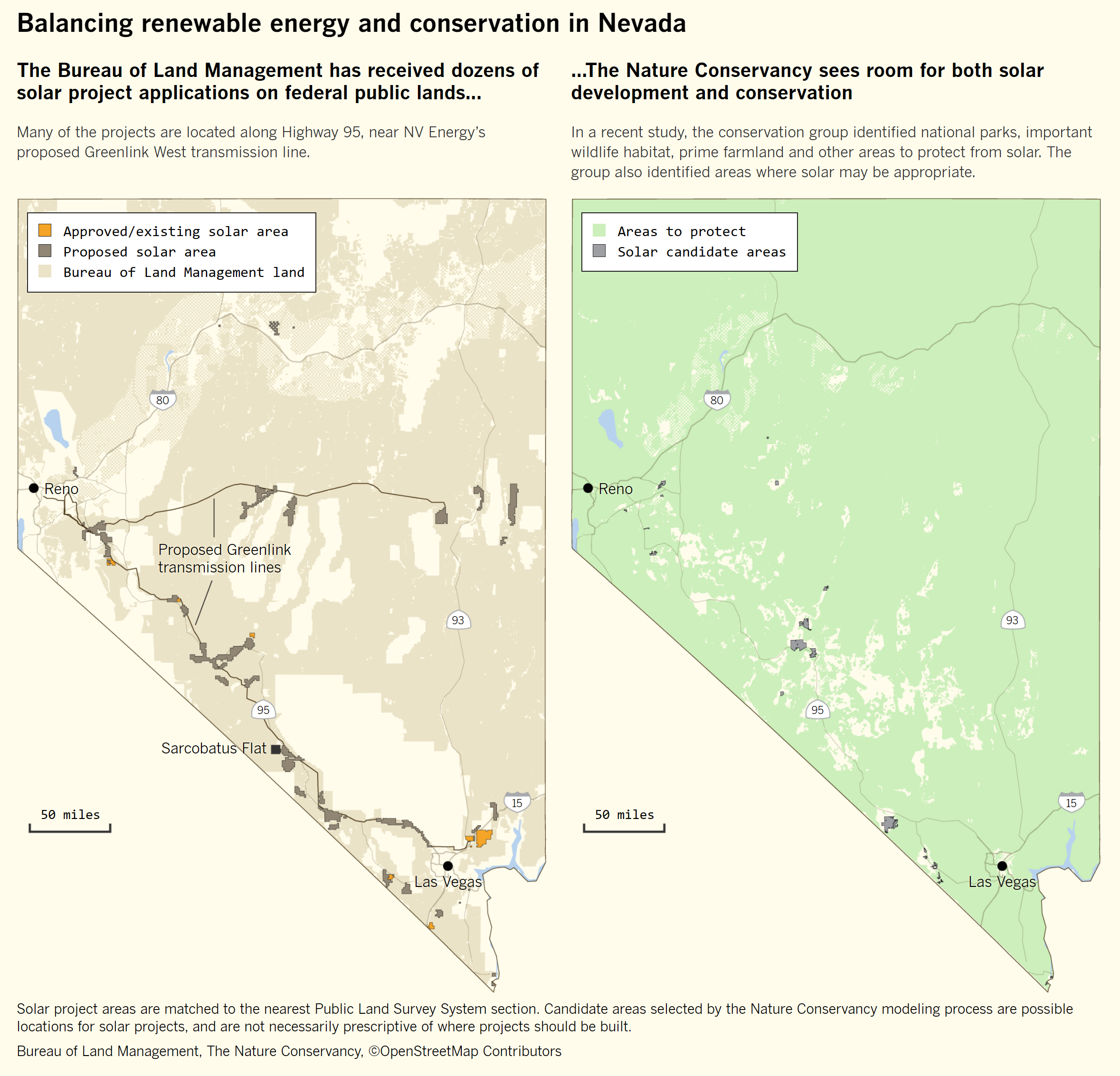

But that hasn’t stopped corporations from making plans to carpet the desert surrounding Las Vegas with dozens of giant solar fields — some of them designed to supply power to California. The Biden administration has fueled that growth, taking steps to encourage solar and wind energy development across vast stretches of public lands in Nevada and other Western states.

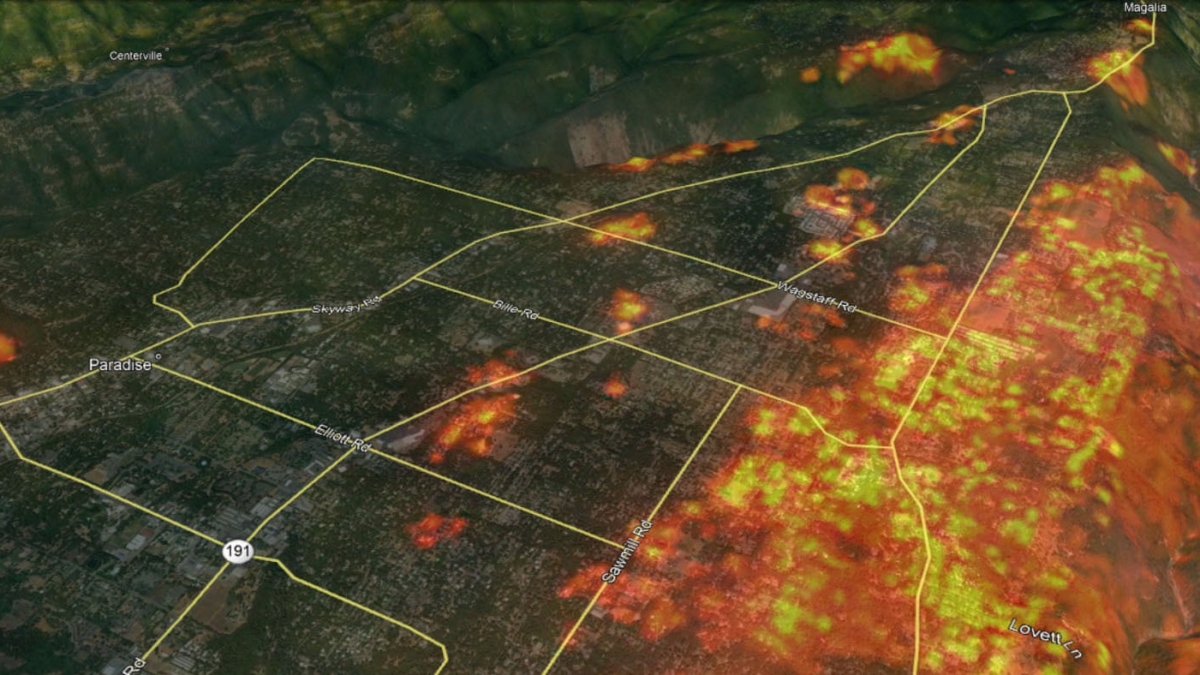

Those energy generators could imperil rare plants and slow-footed tortoises already threatened by rising temperatures.

They could also lessen the death and suffering from the worsening heat waves, fires, droughts and storms of the climate crisis.

Researchers have found there’s not nearly enough space on rooftops to supply all U.S. electricity — especially as more people drive electric cars. Even an analysis funded by rooftop solar advocates and installers found that the most cost-effective route to phasing out fossil fuels involves six times more power from big solar and wind farms than from smaller local solar systems.

But the exact balance has yet to be determined. And Nevada is ground zero for figuring it out.

The outcome could be determined, in part, by billionaire investor Warren Buffett.

The so-called Oracle of Omaha owns NV Energy, the monopoly utility that supplies electricity to most Nevadans. NV Energy and its investor-owned utility brethren across the country can earn huge amounts of money paving over public lands with solar and wind farms and building long-distance transmission lines to cities.

But by regulatory design, those companies don’t profit off rooftop solar. And in many cases, they’ve fought to limit rooftop solar — which can reduce the need for large-scale infrastructure and result in lower returns for investors.

Mike Troncoso remembers the exact date of Nevada’s rooftop solar reckoning.

It was 23 December 2015, and he was working for SolarCity. The rooftop installer abruptly ceased operations in the Silver State after NV Energy helped persuade officials to slash a program that pays solar customers for energy they send to the power grid.

“I was out in the field working, and we got a call: ‘Stop everything you’re doing, don’t finish the project, come to the warehouse,’” Troncoso said. “It was right before Christmas, and they said, ‘Hey, guys, unfortunately we’re getting shut down.’” […]

Some habitat destruction is unavoidable — at least if we want to break our fossil fuel addiction. The key questions are: How many big solar farms are needed, and where should they be built? Can they be engineered to coexist with animals and plants?

And if not, should Americans be willing to sacrifice a few endangered species in the name of tackling climate change?

To answer those questions, Los Angeles Times journalists spent a week in southern Nevada, touring solar construction sites, hiking up sand dunes and off-roading through the Mojave. We spoke with NV Energy executives, conservation activists battling Buffett’s company and desert rats who don’t want to see their favorite off-highway vehicle trails cut off by solar farms.

Odds are, no one will get everything they want.

The tortoise in the coal mine

Biologist Bre Moyle easily spotted the small yellow flag affixed to a scraggly creosote bush — one of many hardy plants sprouting from the caliche soil, surrounded by rows of gleaming steel trusses that would soon hoist solar panels toward the sky.

Moyle leaned down for a closer look, gently pulling aside branches to reveal a football-sized hole in the ground. It was the entrance to a desert tortoise burrow — one of thousands catalogued by her employer, Primergy Solar, during construction of one of the nation’s largest solar farms on public lands outside Las Vegas.

“I wouldn’t stand on this side of it,” Moyle advised us. “If you walk back there, you could collapse it, potentially.”

I’d seen plenty of solar construction sites in my decade reporting on energy. But none like this.

Instead of tearing out every cactus and other plant and leveling the land flat — the “blade and grade” method — Primergy had left much of the native vegetation in place and installed trusses of different heights to match the ground’s natural contours. The company had temporarily relocated more than 1,600 plants to an on-site nursery, with plans to put them back later. [more]

Solar sprawl is tearing up the Mojave Desert. Is there a better way?