Child labor in America is back and it’s as chilling as ever – “You’re taking children from another country and putting them almost in industrial servitude”

By Steve Fraser

13 July 2023

(The Nation) – An aged Native American chieftain was visiting New York City for the first time in 1906. He was curious about the city and the city was curious about him. A magazine reporter asked the chief what most surprised him in his travels around town. “Little children working,” the visitor replied.

Child labor might have shocked that outsider, but it was all too commonplace then across urban, industrial America (and on farms where it had been customary for centuries). In more recent times, however, it’s become a far rarer sight. Law and custom, most of us assume, drove it to near extinction. And our reaction to seeing it reappear might resemble that chief’s—shock, disbelief.

But we better get used to it, since child labor is making a comeback with a vengeance. A striking number of lawmakers are undertaking concerted efforts to weaken or repeal statutes that have long prevented (or at least seriously inhibited) the possibility of exploiting children.

Take a breath and consider this: The number of kids at work in the United States increased by 37 percent between 2015 and 2022. During the last two years, 14 states have either introduced or enacted legislation rolling back regulations that governed the number of hours children can be employed, lowered the restrictions on dangerous work, and legalized subminimum wages for youths.

Iowa now allows those as young as 14 to work in industrial laundries. At age 16, they can take jobs in roofing, construction, excavation, and demolition and can operate power-driven machinery. Fourteen-year-olds can now even work night shifts and once they hit 15 can join assembly lines. All of this was, of course, prohibited not so long ago.

Legislators offer fatuous justifications for such incursions into long-settled practice. Working, they tell us, will get kids off their computers or video games or away from the TV. Or it will strip the government of the power to dictate what children can and can’t do, leaving parents in control—a claim already transformed into fantasy by efforts to strip away protective legislation and permit 14-year-old kids to work without formal parental permission.

In 2014, the Cato Institute, a right-wing think tank, published “A Case Against Child Labor Prohibitions,” arguing that such laws stifled opportunity for poor—and especially Black—children. The Foundation for Government Accountability, a think tank funded by a range of wealthy conservative donors including the DeVos family, has spearheaded efforts to weaken child-labor laws, and Americans for Prosperity, the billionaire Koch brothers’ foundation, has joined in.

Nor are these assaults confined to red states like Iowa or the South. California, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, and New Hampshire, as well as Georgia and Ohio, have been targeted, too. Even New Jersey passed a law in the pandemic years temporarily raising the permissible work hours for 16-to-18-year-olds.

The blunt truth of the matter is that child labor pays and is fast becoming remarkably ubiquitous. It’s an open secret that fast-food chains have employed underage kids for years and simply treat the occasional fines for doing so as part of the cost of doing business. Children as young as 10 have been toiling away in such pit stops in Kentucky and older ones working beyond the hourly limits prescribed by law. Roofers in Florida and Tennessee can now be as young as 12.

Recently, the Labor Department found more than 100 children between the ages of 13 and 17 working in meatpacking plants and slaughterhouses in Minnesota and Nebraska. And those were anything but fly-by-night operations. Companies like Tyson Foods and Packer Sanitation Services (owned by BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management firm) were also on the list.

At this point, virtually the entire economy is remarkably open to child labor. Garment factories and auto parts manufacturers (supplying Ford and General Motors) employ immigrant kids, some for 12-hour days. Many are compelled to drop out of school just to keep up. In a similar fashion, Hyundai and Kia supply chains depend on children working in Alabama.

As The New York Times reported last February, helping break the story of the new child labor market, underage kids, especially migrants, are working in cereal-packing plants and food-processing factories. In Vermont, “illegals” (because they’re too young to work) operate milking machines. Some children help make J. Crew shirts in Los Angeles, bake rolls for Walmart, or work producing Fruit of the Loom socks. Danger lurks. America is a notoriously unsafe place to work, and the accident rate for child laborers is especially high, including a chilling inventory of shattered spines, amputations, poisonings, and disfiguring burns.

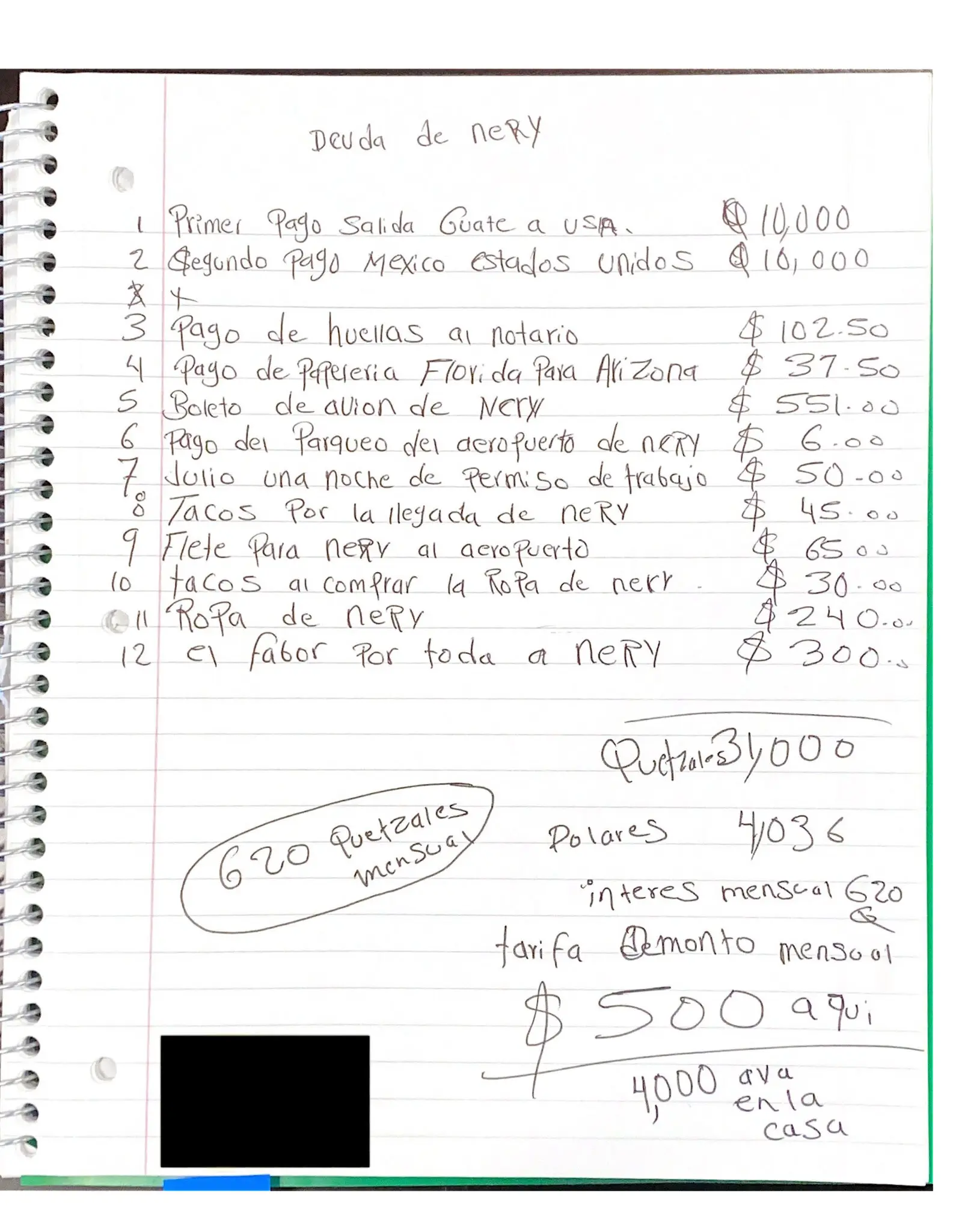

Journalist Hannah Dreier has called it “a new economy of exploitation,” especially when it comes to migrant children. A Grand Rapids, Mich., schoolteacher, observing the same predicament, remarked, “You’re taking children from another country and putting them almost in industrial servitude.” [more]