Climate trauma: people exposed to the deadly Camp Fire in 2018 displayed altered cognitive function months later

By Scott LaFee

18 January 2023

(UC San Diego Today) – In November 2018, the Camp Fire burned a total of 239 square miles, destroyed 18,804 structures and killed 85 people, making it the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history.

Three years later, researchers at University of California San Diego, published a novel study that looked at the psychological consequences, finding that exposure to “climate trauma” for affected residents resulted in increased and chronic mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

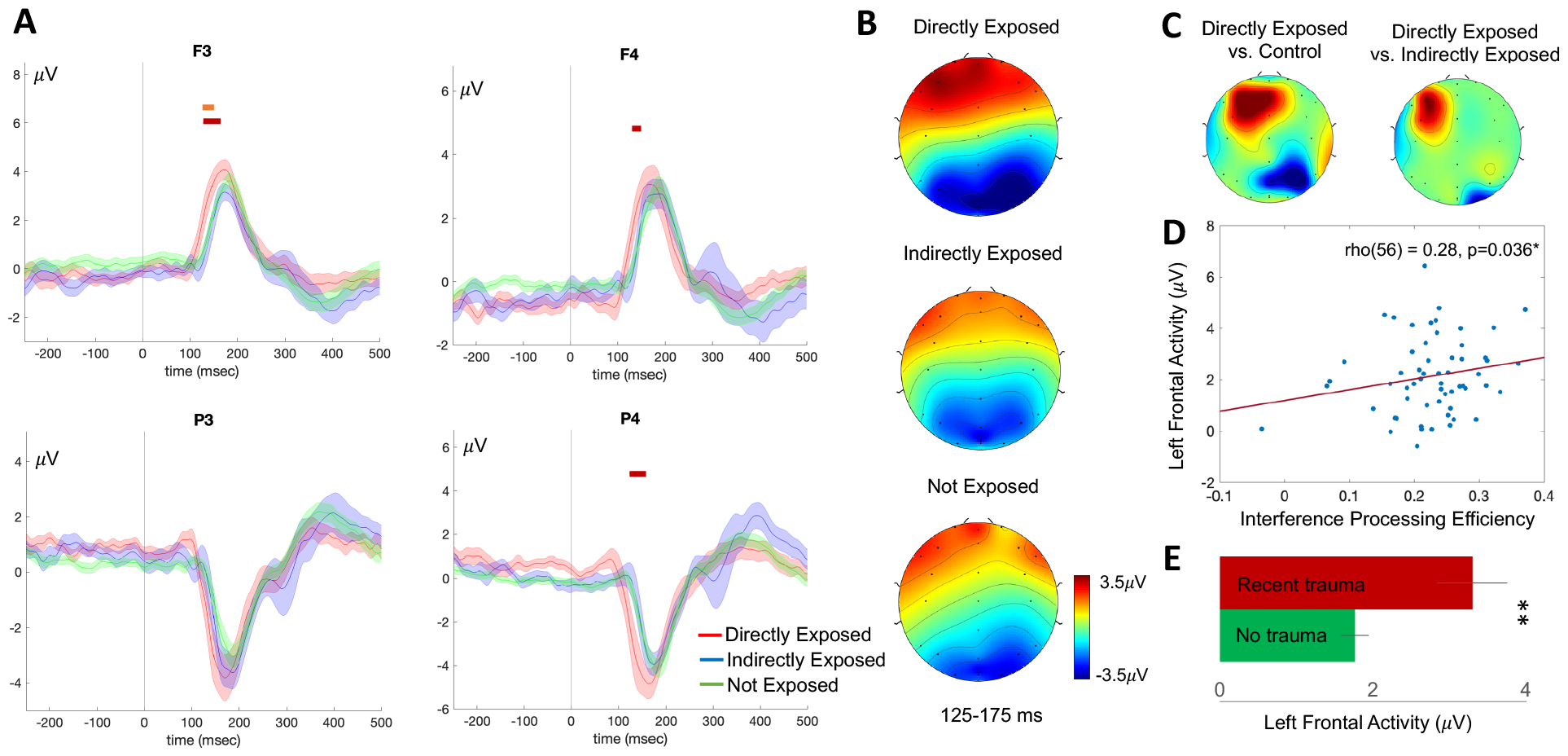

In a new study, published in the 18 January 2023 online issue of PLOS Climate, senior author Jyoti Mishra, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine, director of the Neural Engineering and Translation Labs at UC San Diego, and associate director of the UC Climate and Mental Health Initiative, delved deeper with her colleagues. The study team reported that in a subset of persons exposed to the Camp Fire, significant differences in cognitive functioning and underlying brain activity were revealed using electroencephalography (EEG).

Specifically, the researchers found that fire-exposed individuals displayed increased activity in the regions of the brain involved in cognitive control and interference processing — the ability to mentally cope with unwanted and often disturbing thoughts.

“To function well day-to-day, our brains need to process information and manage memories in ways that help achieve goals while ignoring or dispensing with irrelevant or harmful distractions,” said Mishra.

“Climate change is an emerging challenge. It is already well-documented that extreme climate events result in significant psychological impacts. Warming temperatures, for example, have even been linked to greater suicide rates. As planetary warming amplifies, more forest fires are expected in California and globally, with significant implications for mental health effects.

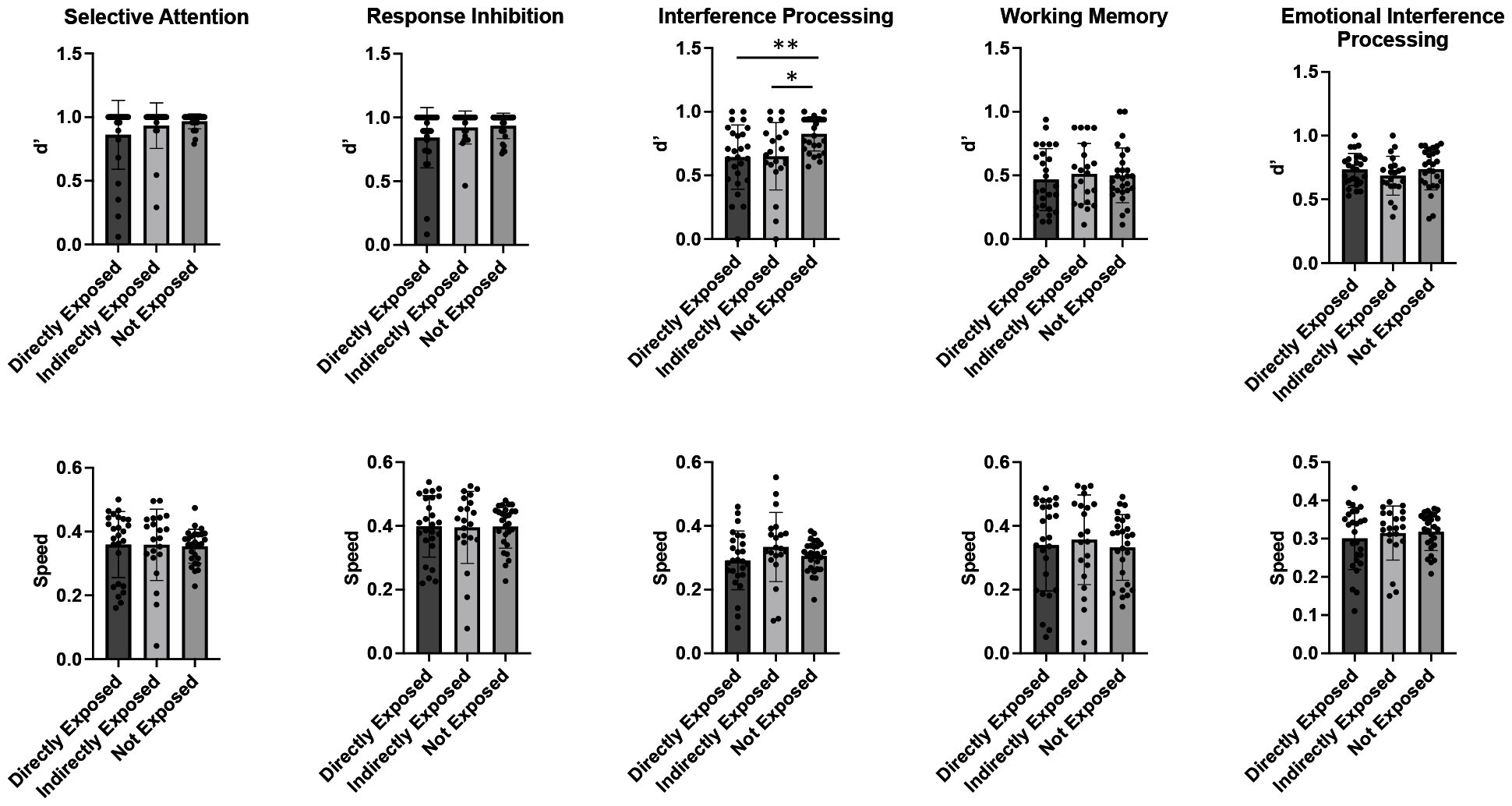

“In this study, we wanted to learn whether and how climate trauma affected and altered cognitive and brain functions in a group of people who had experienced it during the Camp Fire. We found that those who were impacted, directly or indirectly, displayed weaker interference processing. Such weakened cognitive performance may then impair daily functioning and reduce wellbeing.”

The study sample included 27 persons directly exposed to the Camp Fire (for example, their homes were destroyed), 21 who were indirectly exposed (they witnessed the fire but were not directly impacted) and 27 control individuals. All participants underwent cognitive testing with synchronized EEG brain recordings.

Sixty-seven percent of the individuals directly exposed to the fire reported having experienced recent psychological trauma, as did 14 percent of the indirectly exposed individuals. None of the control individuals reported recent trauma exposure.

The EEG recordings showed that the brains of those individuals reporting trauma worked harder at interference processing and cognitive control, suggesting a compensatory effort but at a cost: potentially heightened risk of neurological dysfunction elsewhere.

“The evidence of diminished interference processing, along with altered functional brain responses, is useful because it can help guide efforts to develop resiliency intervention strategies,” said Mishra.

“As the planet warms, more and more individuals will face extreme climate exposures, like wildfires, and having therapeutic tools that can address underlying neuro-cognitive issues will be an important complement to other socio-behavioral therapies.”

Co-authors include: Gillian K. Grennan from UC San Diego; Mathew C. Withers, California State University at Chico; and Dhakshin S. Ramanathan, UC San Diego and VA San Diego Medical Center.

Funding for this research came, in part, from a Tang Prize Foundation grant.

For an additional read, you can find this study on The Conversation.

In the Wake of a Wildfire, Embers of Change in Cognition and Brain Function Linger

Differences in interference processing and frontal brain function with climate trauma from California’s deadliest wildfire

ABSTRACT: As climate change accelerates extreme weather disasters, the mental health of the impacted communities is a rising concern. In a recent study of 725 Californians we showed that individuals that were directly exposed to California’s deadliest wildfire, the Camp Fire of 2018, had significantly greater chronic symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression than control individuals not exposed to the fires. Here, we study a subsample of these individuals: directly exposed (n = 27), indirectly exposed (who witnessed the fire but were not directly impacted, n = 21), versus age and gender-matched non-exposed controls (n = 27). All participants underwent cognitive testing with synchronized electroencephalography (EEG) brain recordings. In our sample, 67% of the individuals directly exposed to the fire reported having experienced recent trauma, while 14% of the indirectly exposed individuals and 0% of the non-exposed controls reported recent trauma exposure. Fire-exposed individuals showed significant cognitive deficits, particularly on the interference processing task and greater stimulus-evoked fronto-parietal activity as measured on this task. Across all subjects, we found that stimulus-evoked activity in left frontal cortex was associated with overall improved interference processing efficiency, suggesting the increased activity observed in fire exposed individuals may reflect a compensatory increase in cortical processes associated with cognitive control. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to examine the cognitive and underlying neural impacts of recent climate trauma.