World Bank calls for sovereign debt changes ahead of looming crises – “There are more Sri Lankas on the way”

By Marc Jones

28 June 2022

LONDON, June 28 (Reuters) – A senior official at the World Bank has ramped up its calls for changes in sovereign debt laws so governments have more control when crises strike and they have to restructure their debt.

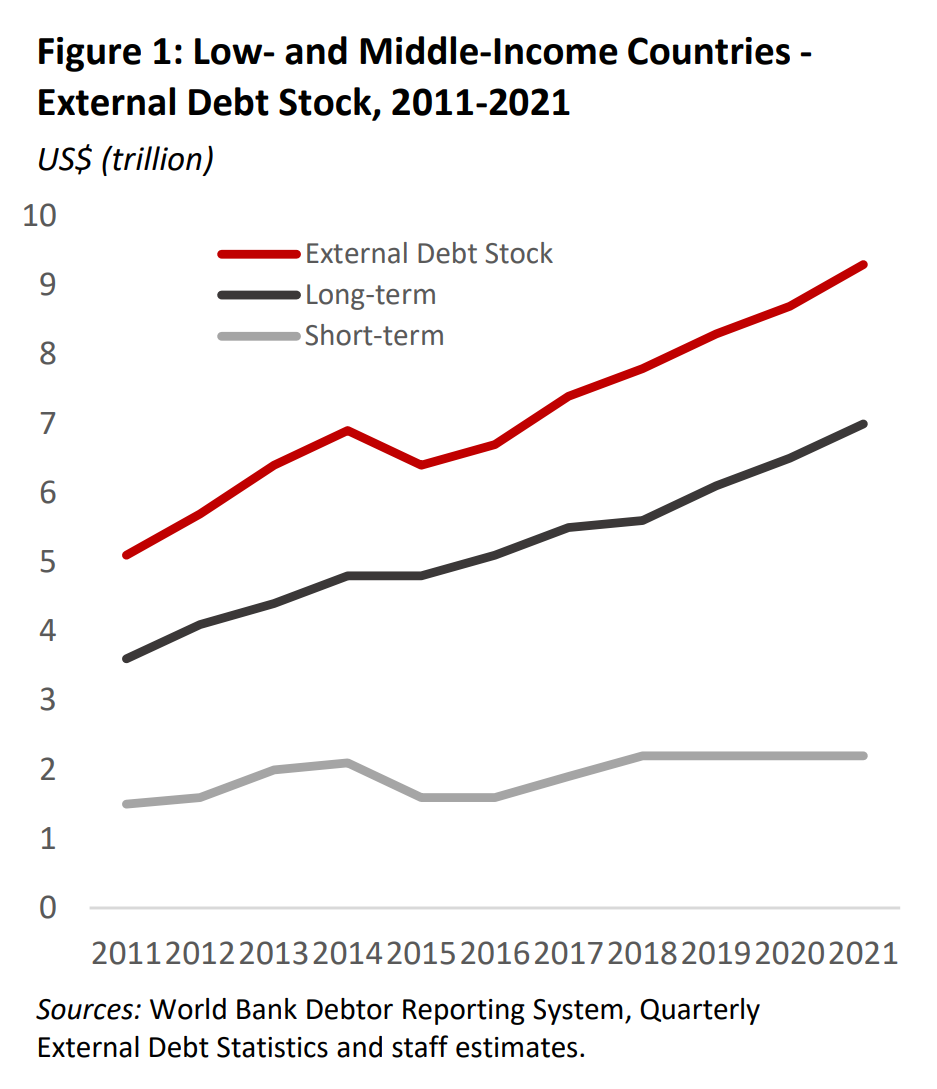

World Bank economists estimate that low- and middle-income economies owe a record $9.3 trillion to foreign creditors and that 40 poor countries, and about half a dozen middle income ones, are either in debt distress or at a high risk of it.

“As global growth fizzles and interest rates surge, the risk of a spate of debt crises is rising – and yet the available mechanisms for tackling them are deeply inadequate,” Indermit Gill, the Bank’s vice president for equitable growth, finance and institutions and sovereign debt lawyer Lee Buchheit said in a blog.

They outlined four key changes that would improve the effectiveness of the so-called Common Framework debt relief plan the Group of Twenty (G20) rich nations launched at the height of COVID-19 pandemic.

First, the blog authors said government bond contracts should stipulate that all creditors have a legal duty to cooperate “in good faith” in sovereign-debt restructurings.

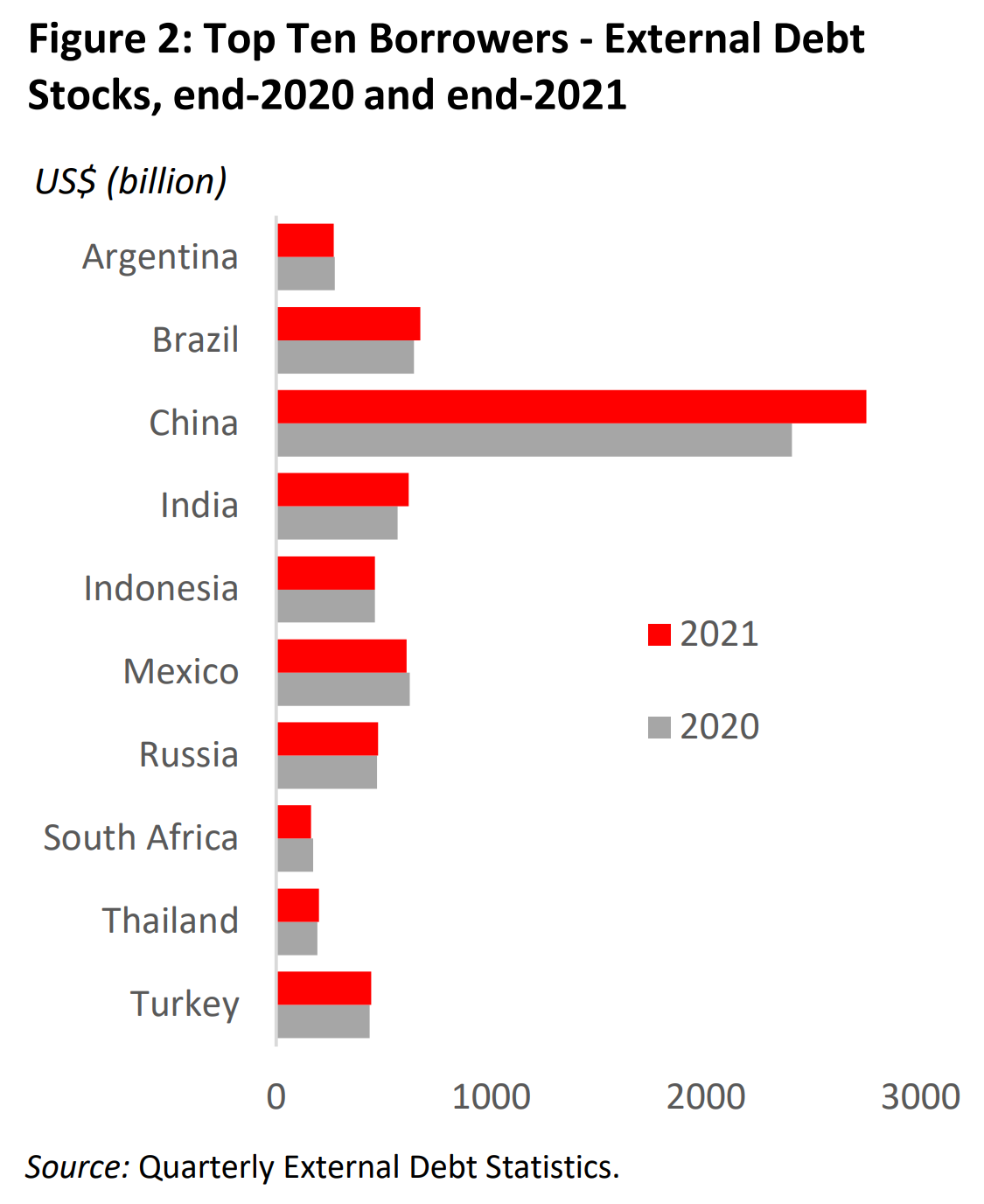

Western governments traditionally negotiate separately to other lenders such as China when countries they both lend to run into trouble. Those efforts are also separate from negotiations by big global investment firms such BlackRock and Vanguard.

Second, all sovereign debt contracts should limit how much a creditor can collect through law suits outside the Common Framework and, in addition, include “Collective Action Clauses” which mean all bonds can be restructured as long as the vast majority of bondholders have agreed.

That in turn would clip the wings of so-called vulture funds that try to hold out and then take governments to court to score a bigger payout for themselves.

Third, it should be made harder for creditors to seize the assets of a debt-distressed government if it has acted in good faith. During one of Argentina’s debt crises, a U.S. hedge fund seized one of its navel ships when it was in Ghana.

Finally, the authors said that while collective action clauses are in many bond contracts issued over the past 20 years, they are not included in syndicated loans which make up a large part of developing country debt and such mechanisms should be retrofitted wherever feasible.

“Governments have a compelling public interest to adopt legislation to end this imbalance,” the blog said, saying legal centres such New York and London would be crucial. “Consider it a long-overdue step to protect their own taxpayers”. [more]

World Bank calls for sovereign debt changes ahead of looming crises

World Bank’s Reinhart sees ‘long haul’ before any debt reductions for developing countries

By Andrea Shalal

29 June 2022

MADRID, June 29 (Reuters) – World Bank chief economist Carmen Reinhart said it could take many more years before the growing number of heavily indebted countries see any substantive reduction in their debts.

Reinhart, who returns to Harvard University on July 1 after a two-year public service leave, said the economic woes facing Sri Lanka were just the tip of the iceberg and more countries would likely join its ranks.

“Be prepared for the long haul,” Reinhart told Reuters in a remote interview.

“My fear – but I think it’s fear founded on the basis of the historical experience – is that to have a comprehensive approach that actually delivers substantive debt reduction will take a long while. Years,” she said, noting that the historical average was around eight years.

Reinhart said Sri Lanka’s woes reflected the balled force of a currency crisis, high inflation, a collapse in output, financial strains and a debt crisis, but other countries were also facing major problems.

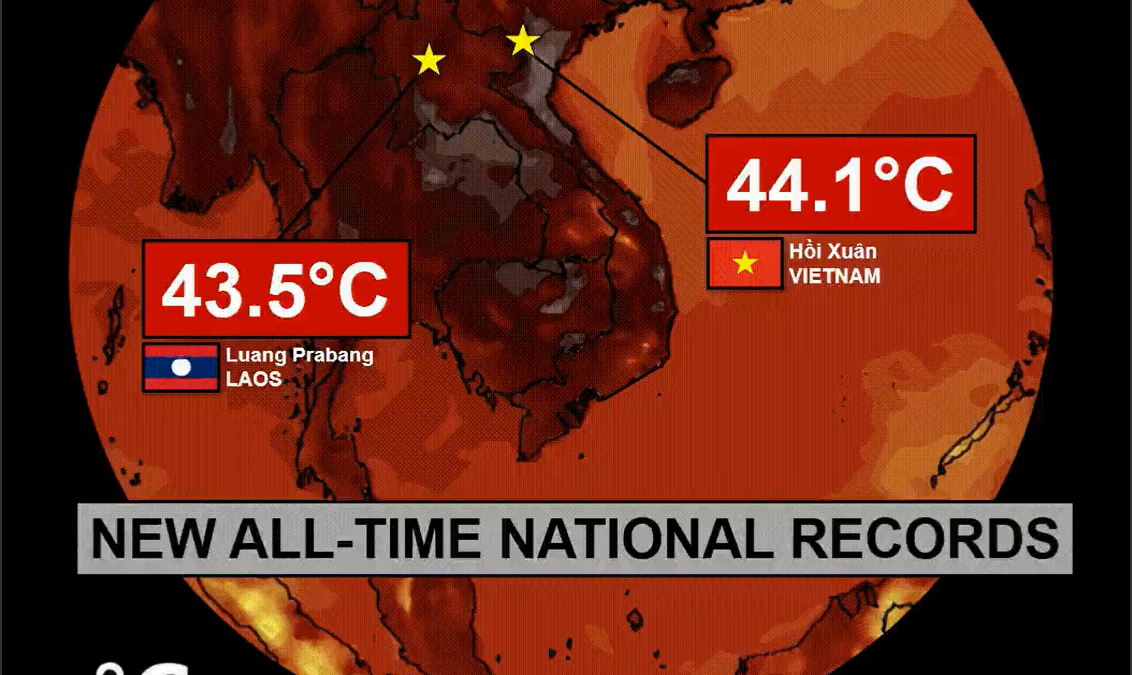

“There are more Sri Lankas on the way. You have countries like Myanmar, Laos. These are not major players in global markets, but they are falling,” she said, noting that others, including Ghana and Egypt, were facing significant shocks as a result of the war in Ukraine and surging food and energy prices.

“There are a lot of countries in precarious situations,” she said.

This ain’t going away quickly. Everyone is preoccupied with their own problems. There’s a tendency to focus on the domestic issues and everything else goes on the back burner. I hate to be like a wet rag, but I do think things will get worse before they get better. We’re still trying to sort out what the new normal is. My sense is that we will see more difficult times before we turn the corner.

World Bank chief economist Carmen Reinhart

Reinhart said the Common Framework for debt treatments agreed to by the Group of 20 major economies and the Paris Club of official creditors in October 2020 had proven to be a disappointment, resulting in not even a single debt restructuring since its launch in October 2020.

She said the lack of progress was not surprising.

“The historical experience has been like pulling teeth, and slow moving at that,” she said. “Every creditor has for their own reasons engaged in foot dragging. China and private creditors have their own incentives to delay.”

Reinhart downplayed the prospects for any significant change in the approach of advanced economies to the mounting issues facing the developing world, including the snowballing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning outcomes and poverty rates.

“This ain’t going away quickly. Everyone is preoccupied with their own problems. There’s a tendency to focus on the domestic issues and everything else goes on the back burner,” she said.

“I hate to be like a wet rag, but I do think things will get worse before they get better. We’re still trying to sort out what the new normal is,” she said. “My sense is that we will see more difficult times before we turn the corner.”

World Bank’s Reinhart sees ‘long haul’ before any debt reductions for developing countries