Somalia faces grim humanitarian catastrophe – “When we lost our livestock, we lost our minds”

By Mariel Müller

17 June 2022

SOMALIA (DW) – In January 2022, Hirsiyow Mohamed and her three children left her drought-stricken village of Drumo in Somalia.

But after 15 days of walking through the hot desert with almost no water and food, she arrived with only one child at the newly built camp for displaced people near the town of Dollow, in the Gedo region of southern Somalia.

“We were walking and walking, and my son was very thirsty and exhausted, Mohamed recalls sadly.

“He asked me many times: ‘Mummy water, mummy water,’ then he started gasping, but there was nothing, no drop of water I could give him,” she told DW.

Her sick 8-year-old daughter died on arrival at the camp. She had been suffering from a bad cough and was weak from the journey.

Children are the most vulnerable as the drought in the Horn of Africa worsens.

The UN projects that 350,000 of the 1.4 million severely malnourished children in Somalia could starve to death if nothing is done.

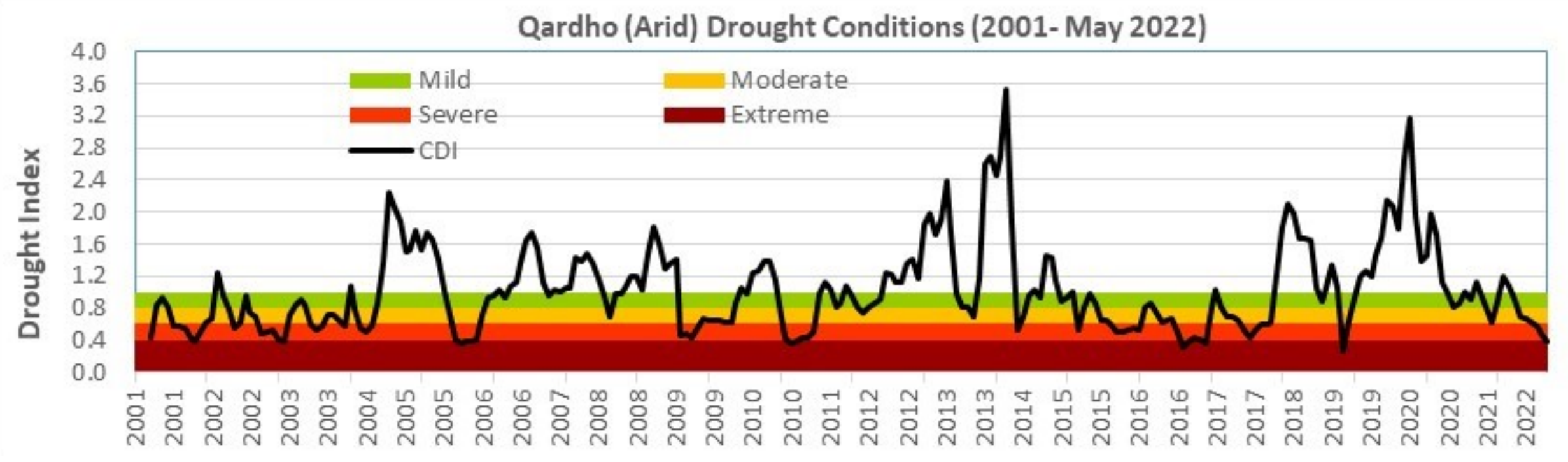

The worst drought in 50 years

Climate change and extreme weather events have increased natural disasters over the last 50 years, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR).

As a result, the international charity organization Oxfam said that more than 23 million people suffer from severe hunger in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, and the autonomous region of Somaliland.

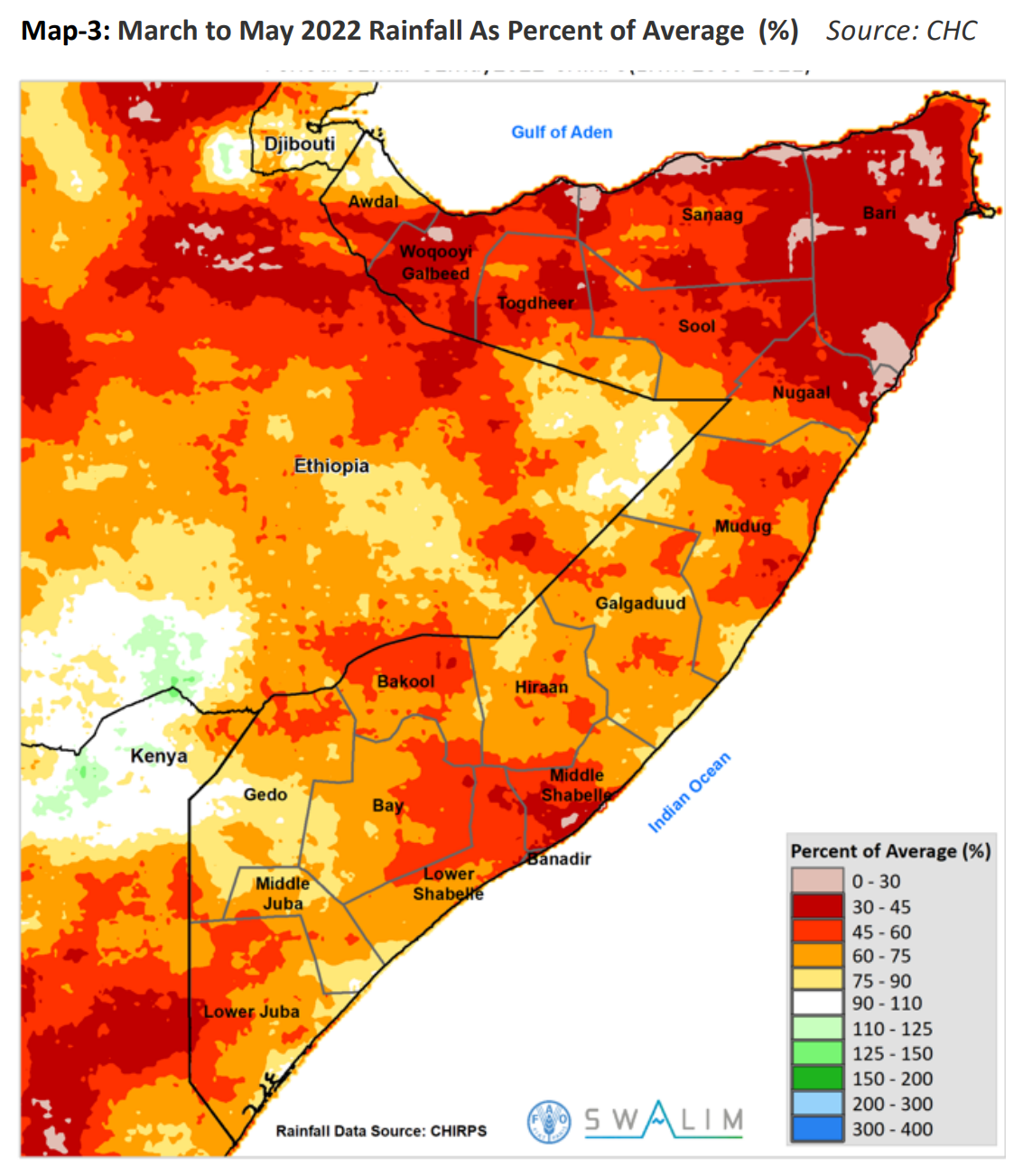

Moreover, there are growing fears that the situation could worsen, as rainfall was scarce in March and early April.

Insufficient rain is forecast for April through June — the rainy season for most of sub-Saharan Africa. This year (2022) would be the third consecutive year where the East African and Horn of Africa regions have not received enough rain.

Although droughts are common in this region, they are becoming more severe. In addition, there is growing scientific evidence that climate change has exacerbated their effects.

Malnourished children

At a clinic near the Gedo camp, DW met mothers waiting for treatment for their malnourished babies. One of the women, Rahmo Nur Wardhere, said she had lost 100 goats due to the drought.

She, too, left her village with her nine children. Without her relatives, they wouldn’t survive, she told DW as she nursed two of her malnourished children.

“I can’t put him down to rest, because he’s sick,” Nur Wardhere said, sounding hopeful because the swelling and fever had reduced.

“When we lost our livestock, we lost our minds. We used to milk the goats for the children. When we lost that, we became desperate. We can’t live without our livestock,” she added.

The drought has driven more than 500,000 people from their homes this year, according to the World Food Programme (WFP). As a result, more than 6 million are now facing acute hunger.

“This drought has the face of a child,” said UNICEF spokesperson Victor Chinyama.

“Not only a child suffering from malnutrition, but there are also other risks, such as early marriage in the case of girls and being recruited in armed groups in the case of boys.” [more]