The next global debt crisis is hiding in plain sight – With emergency debt moratoriums ending, vulnerable households and businesses confront loan repayments they can no longer afford

By Carmen Reinhart and Leora Klapper

2 May 2022

WASHINGTON (Project Syndicate) – When Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, private-debt crises were probably already brewing—albeit hidden from view—in many parts of the world, as a result of the economic disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, the war is pushing even more countries toward similar crises.

The pandemic recovery has always been uneven. According to analysis based on the International Monetary Fund’s most recent World Economic Outlook, per capita income hit a new high in almost 37% of advanced economies in 2021. That share drops to about 27% in middle-income countries and under 21% in low-income countries. And these disparities may be about to deepen.

Debt moratoriums

Early in the pandemic, many countries introduced debt moratoriums, in order to give households and businesses a reprieve at a time when many faced a sharp income decline that left them struggling to meet their obligations.

The moratoriums were often accompanied by policies that gave banks the regulatory flexibility not to reclassify the affected loans in a higher risk category, as is typically required, thereby enabling banks to avoid the higher capital provisioning that reclassification would entail. Policy makers hoped that banks would use the available liquidity to continue lending.

But while the moratoriums did provide temporary relief for private debtors and may have limited the fallout of the early pandemic disruption, they were not without drawbacks. In particular, forbearance policies made it more difficult for banking supervisors to detect the early warning signs of rising loan defaults, resulting in a hidden—but potentially disastrous—nonperforming loan (NPL) problem.

With the emergency moratoriums having now ended in many countries, vulnerable households and businesses, particularly small and medium-size firms, confront loan repayments they can no longer afford. This threatens to lead to a wave of defaults, with far-reaching implications for the economic recovery, especially in the low- and middle-income countries that are already struggling to revive growth.

Denial

There is still time to limit the damage.

But this will require private- and public-sector actors to acknowledge the problem before it erupts into a full-blown crisis and manage it effectively. And so far, there seems to be little appetite for the kind of transparency that this would demand. In fact, according to the data financial institutions have provided to the IMF, there is no problem at all: NPL rates remained flat between 2019 and 2020 in a large sample of advanced and emerging economies that adopted forbearance policies.

Data from the Mastercard Economics Institute, which covers 165 countries, also tells a very different story, with permanent business failures rising nearly 60% in 2020 from their prepandemic (2019) baseline. Although the situation improved in 2021, roughly 15% of countries, most of them low and middle income, still recorded increases in permanent business failures.

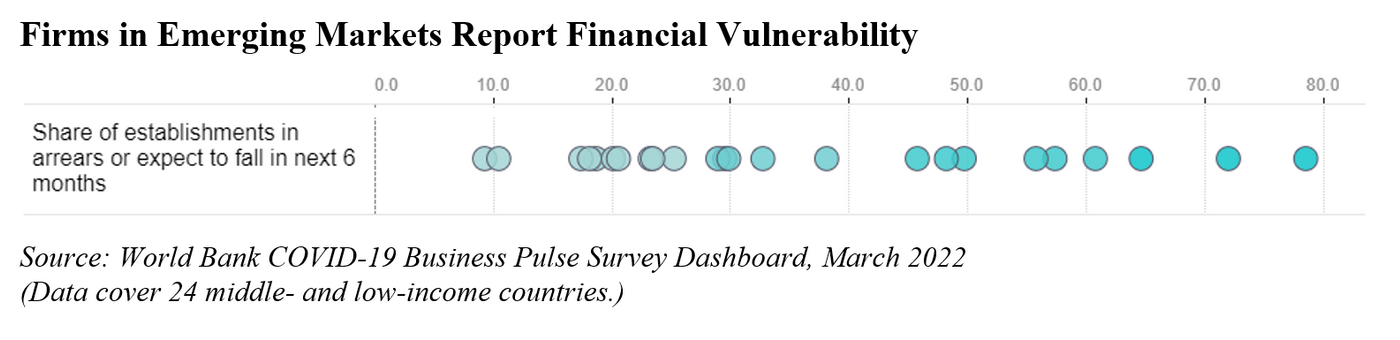

The World Bank Pulse Enterprise Survey, covering 24 low- and middle-income countries, presents a similarly troubled picture. As the chart above shows, as of January 2021, 40% of surveyed businesses expected to be in arrears within six months, including more than 70% of firms in Nepal and the Philippines and over 60% of firms in Turkey and South Africa.

Credit crunch

As more governments unwind debt moratoriums, the risks will only grow. If the past is any guide, rising NPLs will lead to less new lending, as financial institutions attempt to avoid exceeding their capital-provisioning limits and become more risk averse. A credit crunch would not only hamper the economic recovery; it would also exacerbate inequality by disproportionately affecting lending to low-income communities and smaller businesses.

Where one or more systemically important lenders lack the capital to cover their losses, government may need to step in to recapitalize them. This could mean simply transferring the solvency problem to the public sector at a time when governments already face heavy debt burdens and strained budgets.

Russia’s war on Ukraine compounds the risks by intensifying inflationary pressures and undermining the recovery in many emerging-market economies. The war’s impact is particularly acute in Central Asia, where banks are highly exposed to Russian financial institutions and connected to one another via large cross-border remittance flows. New capital and foreign-exchange controls are also creating risks for financial institutions. [more]