A hot, deadly summer is coming in 2022 with frequent blackouts – “We really expect these problems to get worse in the next five years”

By Dan Murtaugh, Rajesh Kumar Singh, and Naureen S. Malik

22 May 2022

(Bloomberg) – Global power grids are about to face their biggest test in decades with electricity generation strangled in the world’s largest economies.

War, drought, shortages, historically low inventories, and a pandemic backlash: energy markets across the planet have been put through the wringer over the past year, and consumers have suffered the consequences of soaring prices. Yet, somehow, things are on track to get even worse.

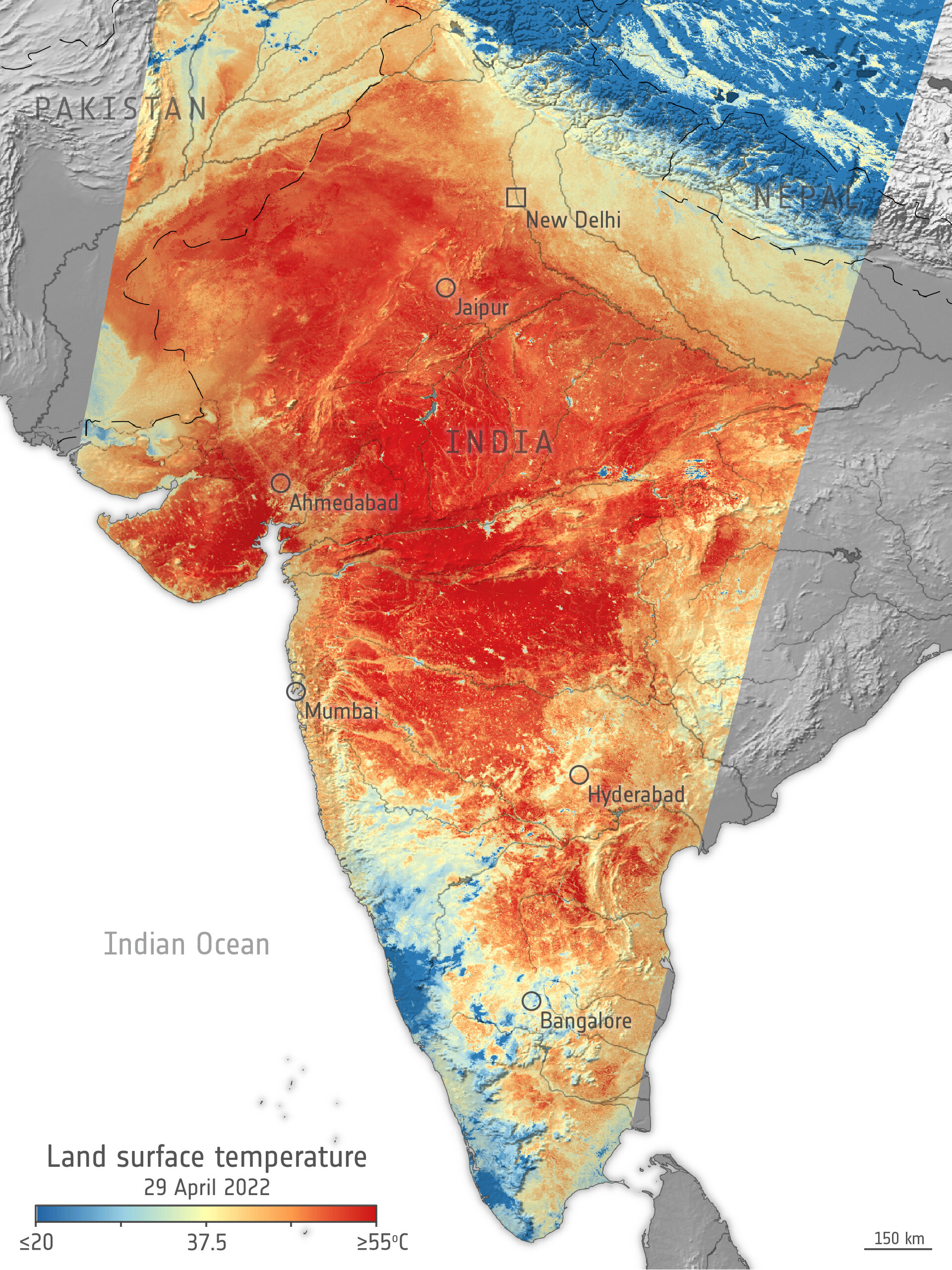

Blame the heat. Summer in much of the Northern Hemisphere is a typical peak for electricity use. This year, it’s going to be sweltering as climate change tightens its grip. It’s already so hot in parts of South Asia that the air temperatures are blistering enough to cook raw salmon. Scientists are predicting scorching months ahead for the US. Power use will surge as homes and businesses crank up air conditioners.

The problem is that energy supplies are so fragile that there just won’t be enough to go around, and power cuts will put lives at risk when there are no fans or air conditioners to provide relief from searing temperatures.

Asia’s heatwave has caused hours-long daily blackouts, putting more than 1 billion people at risk across Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and India, with little relief in sight. Power supplies will be tight in China and Japan.

Six Texas power plants failed earlier this month as the summer heat just began to arrive, offering a preview of what’s to come. At least a dozen US states from California to the Great Lakes are at risk of electricity outages this summer.

South Africa is poised for a record year of power cuts. And Europe is in a precarious position that’s held up by Russia – if Moscow cuts off natural gas to the region, that could trigger rolling outages in some countries.

“War and sanctions are disrupting supply and demand, and that’s coupled with extreme weather and an economic rebound from Covid boosting power demand,” said Shantanu Jaiswal, a BloombergNEF analyst. “The confluence of so many factors is quite unique. I can’t recall the last time they all happened together.”

Without power, human welfare will be under duress. Poverty, age, and proximity to the equator will increase the likelihood of illness and death from unrelenting temperatures. Prolonged outages would mean that tens of thousands may also lose access to clean water.

If blackouts persist, and businesses shutter, that will also bring huge economic shocks.

In India, power shortages in many states are already nearing the levels to those from 2014, when they were estimated to have shaved about per cent off the country’s gross domestic product. That would mean a reduction of almost US$100 billion should the outages become more widespread and last through the year.

A run on electricity would also likely contribute to more gains for power and fuel markets, raising utility bills and further fanning inflation.

The world is grappling with “more than two years of global supply chain distress caused by the pandemic, the spreading fallout from the war in Ukraine and extreme weather caused by climate change,” said Henning Gloystein, an analyst at Eurasia Group.

“The main risk is that if we see major blackouts on top of all the aforementioned problems this year, that could trigger some form of humanitarian crisis in terms of food and energy shortages on a scale not seen in decades.”

This year might enter the record books for the biggest-ever strain on global power, but the hurdles aren’t likely to go away any time soon. Climate change means that the extreme heatwaves of today will become more common, continuing to mount pressure on electricity supplies.

At the same time, a lack of investment in fossil fuels in recent years coupled with strong demand growth, especially in Asian emerging markets, should keep markets tight for the next few years, said Alex Whitworth, an analyst with Wood Mackenzie Ltd in Shanghai.

While wind and solar’s share of total capacity is expected to soar over the next decade, until energy storage facilities catch up to the shift, that will place even more stress on grids, Whitworth said.

“You’ll be facing a supply scare every time there’s clouds or storms or a wind drought for a week,” he said. “We really expect these problems to get worse in the next five years.”

Of course, the switch to renewable power is crucial in the fight against climate change. Burning even more coal now to cope with the energy shortage would just increase emissions, creating a vicious cycle that can lead to more heatwaves and more strain on grids. [more]