World Bank’s 2021 Year in Review in 11 Charts: The Inequality Pandemic

By Venkat Gopalakrishnan, Divyanshi Wadhwa, Sara Haddad, and Paul Blake

21 December 2021

(World Bank) – From uneven economic recovery to unequal access to vaccines; from widening income losses to divergence in learning, COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on the poor and vulnerable in 2021. It is causing reversals in development and is dealing a setback to efforts to end extreme poverty and reduce inequality. Because of the pandemic, extreme poverty rose in 2020 for the first time in over 20 years and around 100 million more people are living on less than $1.90 a day. Through this series of charts and graphs, we share select research from the World Bank Group that illustrates the severity of the pandemic as it enters its third year. We also reflect on the Bank’s rapid and innovative response to the crisis.

1. Unequal Vaccines Access

The quickest way to end the pandemic is by vaccinating the world. However, with just over 7 percent of people in low-income countries receiving a dose of the vaccines compared to over 75 percent in high-income countries, we need fair and broad access to effective and safe COVID-19 vaccines to save lives and strengthen global economic recovery.

The World Bank has approved financing for vaccine purchase and deployment in over 64 countries, amounting to $6.3 billion. So far, almost 300 million COVID vaccine doses are under Bank contract for developing countries. The Bank has also partnered with COVAX and with the African Union to support the Africa Vaccine Acquisition Trust (AVAT), which will help countries purchase and deploy vaccines for up to 400 million people. The Bank Group has also joined forces with IMF, WTO, and WHO to convene the Multilateral Leaders Task Force on COVID-19 to step up coordination among multilateral institutions, governments, and the private sector to accelerate access to COVID-19 vaccines and other essential health tools for developing countries by leveraging multilateral finance and trade solutions. In addition, World Bank financing has helped countries purchase PPE, therapeutics, diagnostics and oxygen products.

* Vaccine projects continue to be approved late into the year. For the most up-to-date data, please visit our COVID-19 Vaccines Hub

2. Are countries ready to deploy vaccines?

While access to vaccines is critical to saving lives, countries also need the underlying infrastructure to ensure successful delivery and distribution of vaccines. The pandemic has exposed—more than ever before—the weaknesses in so many health systems, which now face the dual challenge of responding to the outbreak and maintaining essential, life-saving services. It also shows that strong health systems are the foundation of pandemic preparedness. The Bank is supporting countries to invest in better preparedness by having resilient health systems that can detect, identify, treat, and halt transmission of deadly viruses.

The Bank, along with partners, assessed countries’ readiness to safely deploy COVID-19 vaccines in more than 140 countries. As countries have begun to vaccinate their populations, these assessments provide highly valuable insights into countries’ preparedness. They show that most countries are focusing on strengthening essential aspects of the vaccine delivery chain, critical to advance vaccination schedules and inoculating their populations. Although countries have some gaps in readiness, most have prepared well enough in some essential areas.

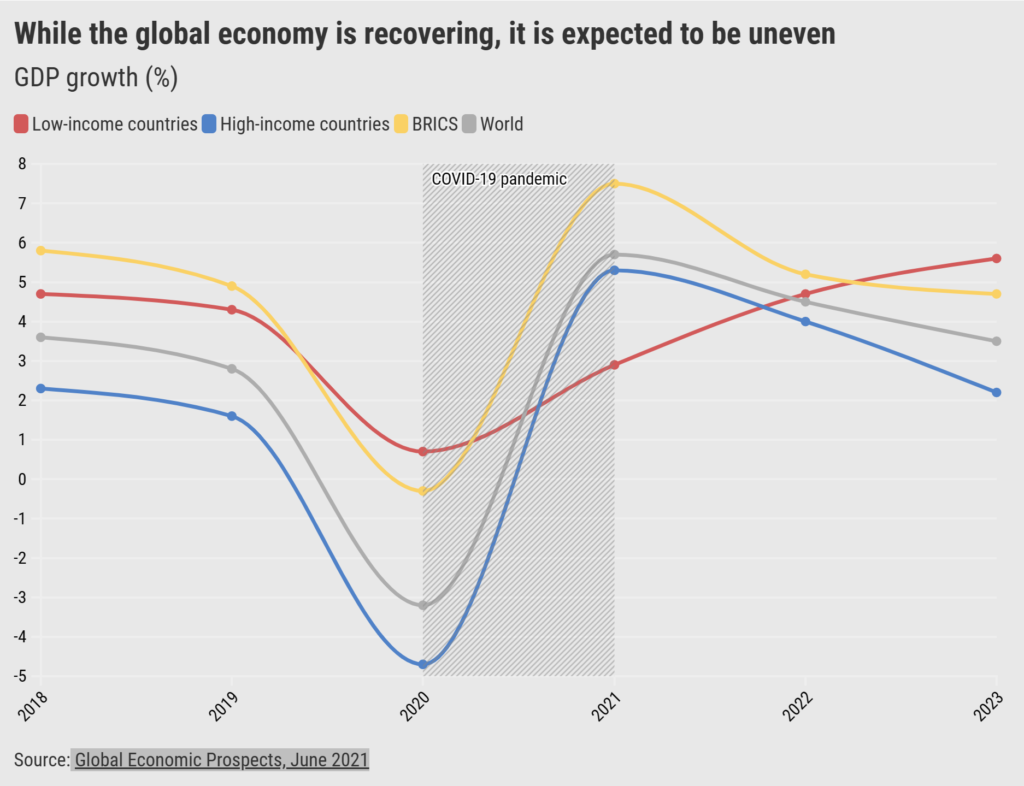

3. Uneven Global Recovery

The June edition of the Global Economic Prospects noted that while the global economy is set to expand 5.6 percent in 2021—its strongest post-recession pace in 80 years, the recovery will be uneven. Low-income economies are forecast to expand by only 2.9 percent in 2021, the slowest growth in the past 20 years, other than 2020, partly due to the slow pace of vaccination. An update to the Global Economic Prospects is expected in January.

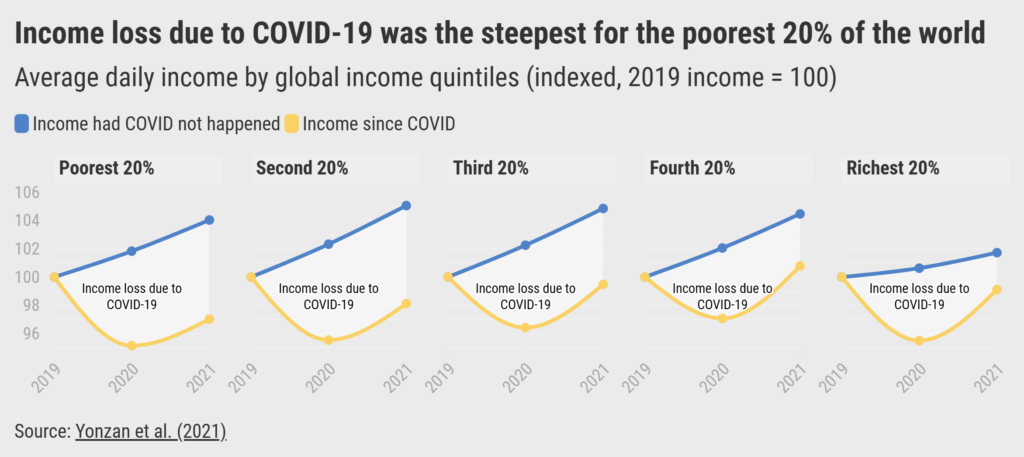

4. Income Losses for the Poorest 40 percent

This inequality in recovery becomes quite telling when it comes to income losses, as outlined in this blog.

While people across all income groups experienced losses during the pandemic, the poorest 20 percent experienced the steepest decline in incomes. In 2021, their incomes declined further while the richest have begun to stem the tide. That’s because the poorest 40 percent haven’t started to recover their income losses. The decline in incomes has translated into around 100 million more people living in extreme poverty.

Not surprisingly, men and women have experienced the crisis in markedly different ways. A review of data by the Bank and other partners show that women have lost out more than men in terms of jobs, income, and safety.

5. Trade – An Engine for Global Recovery

It isn’t a coincidence that the increase in extreme poverty has happened when there have been pandemic-influenced trade disruptions. Historically, there is a close connection between trade and poverty reduction with low- and middle-income countries almost doubling their share of exports between 1990 and 2017, a period which saw a decline in extreme poverty.

Trade also plays a crucial role in economic recovery, as evidenced by a recent World Bank report. After the pandemic severely disrupted global trade, we are witnessing a robust rebound, which is helping with the recovery. Trade contributes to speeding up economic recovery from the pandemic by providing sustained foreign demand for exports and ensuring the availability of imported intermediate products and services. The Least Developed Countries, which have limited ability to spur recovery through fiscal stimulus packages, are particularly dependent on trade recovery as a source of economic growth. With the pandemic highlighting the need to keep critical goods flowing through borders, the Bank Group is supporting country-led reforms to limit the impact of the pandemic and foster economic recovery.

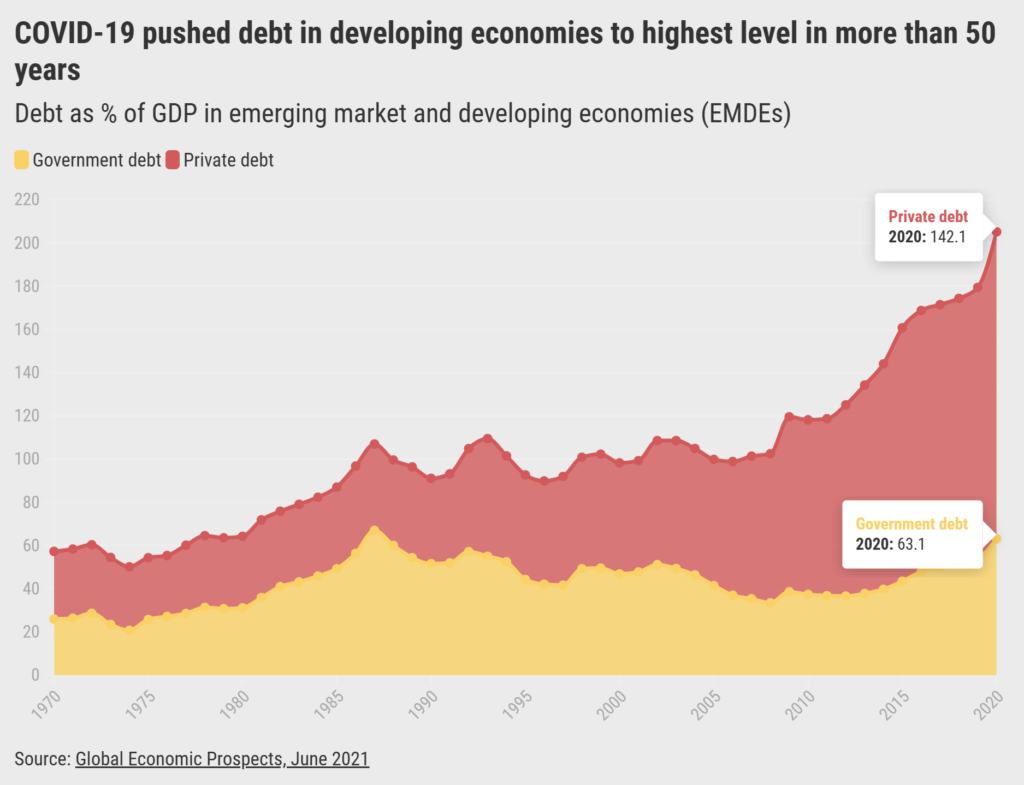

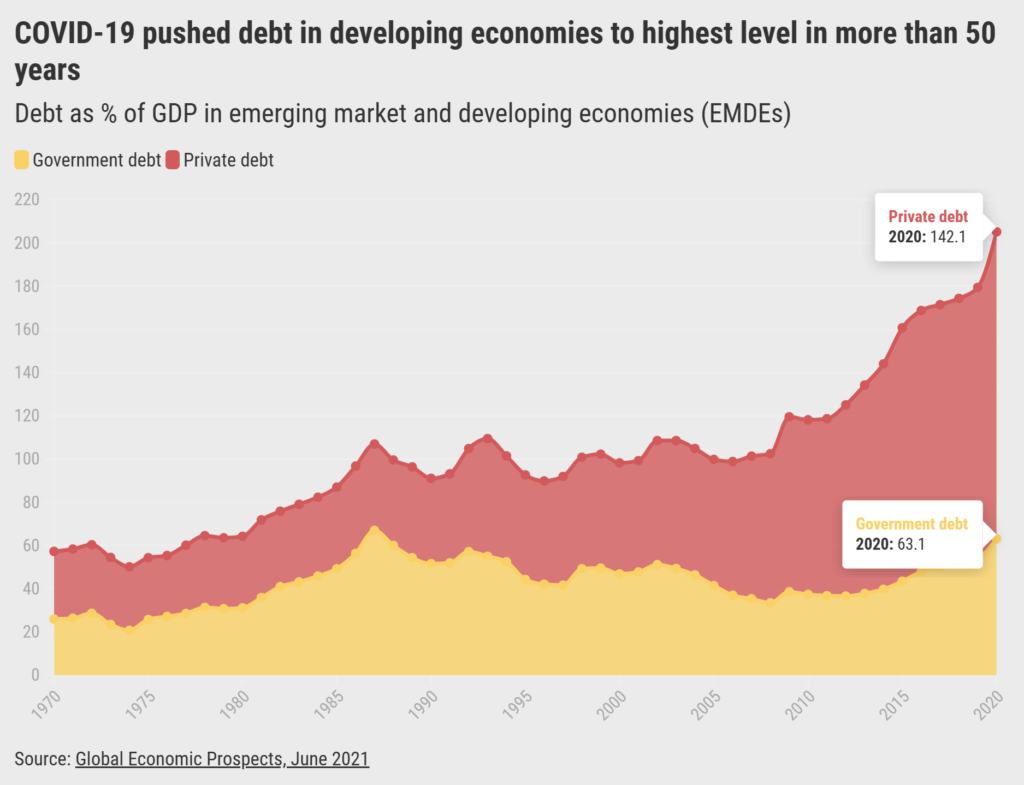

6. Rising Debt Levels Amid the Pandemic

Debt loads in emerging market and developing economies have spiked during the pandemic. The challenge is acute in low-income countries – half of which were in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress before COVID-19 arrived. This comes after a decade that saw the fastest, biggest, and broadest expansion of debt levels around the world, according to the Global Economic Prospects.

As policy makers in emerging market and developing economies look to shift from pandemic response to recovery, they’ll need to be careful not to prematurely withdraw fiscal support and look to increase the efficiency of public spending – all while balancing the need for debt sustainability.

Still, the debt burden will be felt long after the virus abates, as servicing costs rise, slowing recoveries and hindering efforts to address other development challenges – including climate change.

7. Complexity of Debt Reporting

There is more to debt than what meets the eye, if one goes by the findings of the Debt Transparency in Developing Countries report. That’s because reporting on debt isn’t a very straightforward exercise.

Global debt surveillance today depends on a patchwork of databases with different standards and definitions. They contain large gaps: the report shows that publicly available tallies of debt stocks in low-income countries can vary by as much as 30 percent of a country’s GDP because of divergent definitions and standards in local and international databases

As World Bank Group President David Malpass wrote in the report’s foreword, achieving “greater debt transparency is a vital step in the development process. It facilitates new, high-quality investment, reduced corruption, and provides accountability.”

8. Unprecedented Increase in Learning Poverty

One of COVID-19’s devastating impacts on the poor and vulnerable can be witnessed in the field of education. It dealt a severe blow to the lives of young children, students, and youth and further exacerbated inequalities in education. Due to prolonged school closures and poor learning outcomes, recent World Bank estimates document that increases in learning poverty – the share of 10-year-olds who cannot read a basic text – could reach 70 percent in low- and middle-income countries.

This will have lasting impacts on future earnings, poverty alleviation, and reducing inequality. According to latest estimates, this generation of students now risks losing $17 trillion in lifetime earnings. In response to the deepening education crisis, the Bank has rapidly ramped up its support to developing countries, with projects reaching at least 432 million students and 26 million teachers – one-third of the student population and nearly a quarter of the teacher workforce in current client countries.

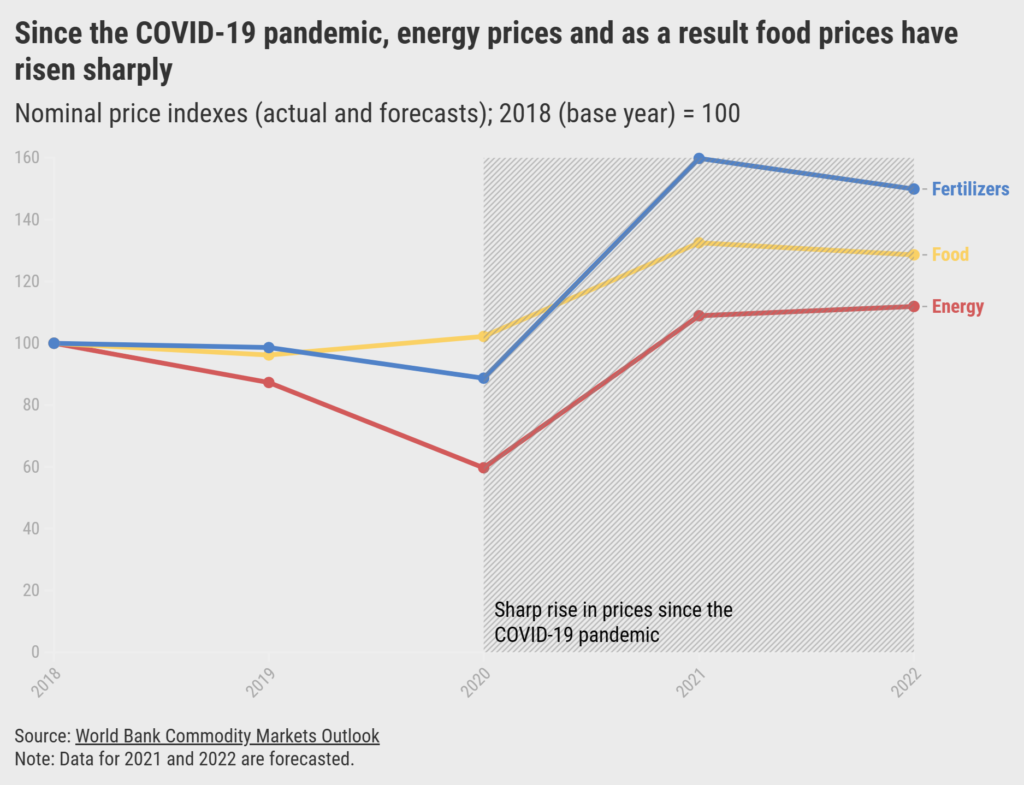

9. High Energy Prices Fueling Rise in Other Commodity Costs

The picture of commodity prices isn’t rosy either. According to the latest Commodity Markets Outlook, energy prices are expected to average more than 80 percent higher in 2021 compared to the previous year.

Since energy is a critical commodity for food production and heating, these soaring prices can have downstream implications. Higher energy prices have already affected fertilizer prices, in turn increasing the cost of food production.

However, in the latter half of 2021, food commodity prices have begun to stabilize in response to favorable global supply outlook, but they are still above pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, domestic food price inflation is rising in most countries, reducing poor people’s ability to afford healthy food. This can exacerbate food insecurity in developing countries.

10. The Urgency of the Climate Crisis

As COVID-19 has caused immediate reversals in fortunes for the poor and vulnerable, one cannot lose sight of the challenges of climate change and the urgent action they demand.

If unchecked, climate change can push up to 132 million people into extreme poverty by 2030 according to World Bank estimates and most of the world’s poorest people will live in situations characterized by fragility, conflict, and violence. Poverty is already intertwined with vulnerability to climate-related threats such as flooding and vector-borne diseases, making climate change a major impediment to alleviating extreme poverty.

11. Growing Number of Climate-Induced Internal Migrants by 2050

In addition to contributing to an increase in extreme poverty, climate change can also act as a powerful driver of internal migration. The latest Groundswell Report finds that by 2050 climate change could lead 216 million people to move within their countries.

There is still an opportunity to significantly reduce these numbers and better manage internal climate migration if there is a concerted global effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while at the same time supporting green, inclusive, and resilient development.

To act on the urgent challenges, the World Bank Group released its new Climate Change Action Plan 2021-2025 that aims to deliver record levels of climate finance to developing countries, reduce emissions, strengthen adaptation, and align financial flows with the goals of the Paris Agreement. The Action Plan for 2021-25 broadens World Bank Group efforts from investing in “green” projects to helping countries fully integrate their climate and development goals.

The Bank Group is the biggest multilateral funder of climate investments in developing countries and between 2016 and 2021 we delivered over $109 billion in climate finance including a record $26 billion in FY21. The World Bank has also boosted climate adaptation support from 40 percent of climate finance in 2016 to 52 percent in 2020. We are supporting our countries so that they are prepared for the low-carbon, resilient transition, enabling them to build climate-smart economies.

Conclusion

2021 has shown that the impact of the pandemic is far-reaching and has touched every possible area of development. With the poor and the vulnerable bearing the brunt of it, the pandemic is dealing a severe setback to ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity. But it isn’t all doom and gloom. As the year went on, there were some positive developments — global economy grew, goods trade rebounded, food commodity prices have begun to stabilize, and remittances registered a robust recovery. However, with newer variants and unequal access to vaccines, there is still more to work to be done.

At the same time, as some countries are beginning to chart their recovery, it is also an opportunity for them to achieve lasting economic growth without degrading the environment or aggravating inequality. The Bank Group is helping countries chart a recovery that is green, resilient, and inclusive through achieving economic stability and growth, leveraging the digital revolution, making development greener and more sustainable, and investing in people. [more]

One Response

Comments are closed.