“Fast and dramatic” permafrost thaw will double previous estimates of potential carbon emissions – “Forests can become lakes in the course of a month”

By Natacha Larnaud

4 February 2020

(CBS News) – Rapidly thawing permafrost in the Arctic has scientists worried. According to a new study published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience, the ice that holds the soil together is melting, causing hillsides to collapse and massive sinkholes to open up as a result. And that dramatic disruption to the landscape is only part of the story — a bigger concern is the growing amount of carbon this process releases into the atmosphere.

The rapid melting of previously solid permafrost promotes microbial activity, which releases greenhouse gases like CO2 and methane into the atmosphere, causing carbon levels to rise. Higher carbon levels, in turn, contribute to global warming. The study warns that the level of emissions from the Arctic could be much higher than previously estimated.

Merritt Turetsky, lead author of the study, said the abrupt thawing is “fast and dramatic” and “affects landscapes in unprecedented ways.”

“Abrupt thawing of permafrost will double previous estimates of potential carbon emissions from permafrost thaw in the Arctic,” Turetsky said in a press release.

“Forests can become lakes in the course of a month, landslides occur with no warning, and invisible methane seep holes pose threats to the safety of hunters and snowmobilers traveling across the land.”

The new study distinguishes between gradual permafrost thaw, which affects permafrost and its carbon stores slowly, versus more abrupt types of permafrost thaw.

Less than 20% of northern permafrost is susceptible to this kind of rapid thaw, which occurs where permafrost contains high levels of ice in the ground. Permafrost that abruptly thaws is what scientists are worried about because it is a large emitter of carbon, including the release of carbon dioxide and methane, which is an even more potent greenhouse gas.

The researchers say that even though at any given time less than 5% of the Arctic permafrost region is likely to be experiencing abrupt thaw, their emissions will equal those of areas experiencing gradual thaw.

“Where permafrost tends to be frozen lake sediment or organic soils, the type of earth material that can hold a lot of water, these are like sponges on the landscape,” Turetsky said. “When you have thaw, we see really dynamic and rapid changes.”

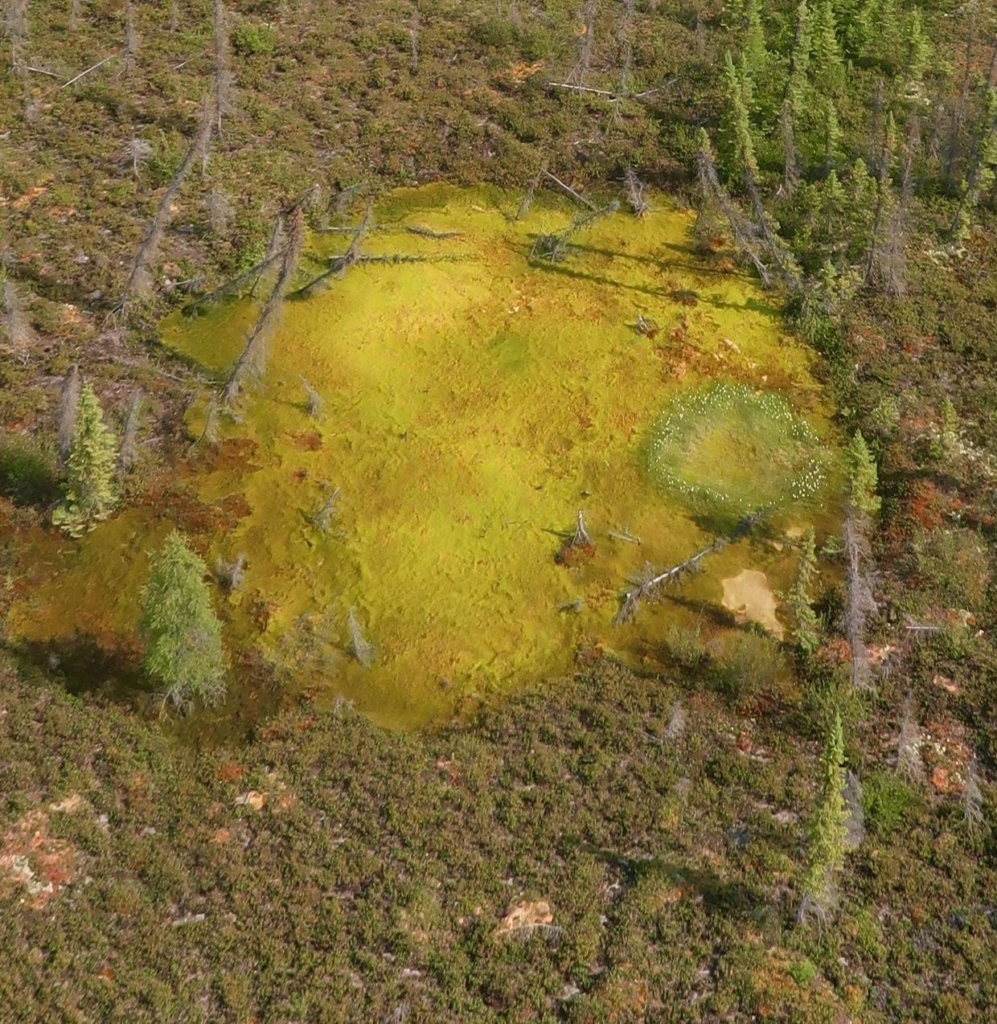

When ice-rich permafrost thaws, it leads to a phenomenon known as thermokarst, which results in the land surface being ravaged. This process happens naturally in some places, but it is accelerating with global warming and rapid thaw. Thermokarst depressions or landslides can now develop very quickly, in the matter of days to weeks, leading to extreme consequences for the landscape and the atmosphere.

“Abrupt permafrost thaw can occur in a variety of ways, but it always represents a dramatic abrupt ecological shift,” Turetsky said. “Systems that you could walk on with regular hiking boots and that were dry enough to support tree growth when frozen can thaw, and now all of a sudden these ecosystems turn into a soupy mess.”

The Arctic is warming at more than two times the pace of the world as a whole. [more]

Permafrost is thawing so quickly in the Arctic it’s leaving sinkholes

Arctic permafrost thaw plays greater role in climate change than previously estimated

By Kelsey Simpkins

3 February 2020

(CU Boulder Today) – Abrupt thawing of permafrost will double previous estimates of potential carbon emissions from permafrost thaw in the Arctic, and is already rapidly changing the landscape and ecology of the circumpolar north, a new CU Boulder-led study finds.

Permafrost, a perpetually frozen layer under the seasonally thawed surface layer of the ground, affects 18 million square kilometers at high latitudes or one quarter of all the exposed land in the Northern Hemisphere. Current estimates predict permafrost contains an estimated 1,500 petagrams of carbon, which is equivalent to 1.5 trillion metric tons of carbon.

The new study distinguishes between gradual permafrost thaw, which affects permafrost and its carbon stores slowly, versus more abrupt types of permafrost thaw. Some 20% of the Arctic region has conditions conducive to abrupt thaw due to its ice-rich permafrost layer. Permafrost that abruptly thaws is a large emitter of carbon, including the release of carbon dioxide as well as methane, which is more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. That means that even though at any given time less than 5% of the Arctic permafrost region is likely to be experiencing abrupt thaw, their emissions will equal those of areas experiencing gradual thaw.

Emissions across 2.5 million km2 of abrupt thaw could provide a similar climate feedback as gradual thaw emissions from the entire 18 million km2 permafrost region.

Turetsky, et al., 2020 / Nature Geoscience

This abrupt thawing is “fast and dramatic, affecting landscapes in unprecedented ways,” said Merritt Turetsky, director of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at CU Boulder and lead author of the study published today in Nature Geoscience. “Forests can become lakes in the course of a month, landslides occur with no warning, and invisible methane seep holes can swallow snowmobiles whole.”

Abrupt permafrost thaw can occur in a variety of ways, but it always represents a dramatic abrupt ecological shift, Turetsky added.

“Systems that you could walk on with regular hiking boots and that were dry enough to support tree growth when frozen can thaw, and now all of a sudden these ecosystems turn into a soupy mess,” Turetsky said.

Why thawing permafrost matters

Permafrost contains rocks, soil, sand, and in some cases, pockets of pure ground ice. It stores on average twice as much carbon as is in the atmosphere because it stores the remains of life that once flourished in the Arctic, including dead plants, animal and microbes. This matter, which never fully decomposed, has been locked away in Earth’s refrigerator for thousands of years.

As the climate warms, permafrost cannot remain frozen. Across 80 percent of the circumpolar Arctic’s north, a warming climate is likely to trigger gradual permafrost thaw that manifests over decades to centuries.

But in the remaining parts of the Arctic, where ground ice content is high, abrupt thaw can happen in a matter of months – leading to extreme consequences on the landscape and the atmosphere, especially where there is ice-rich permafrost. This fast process is called “thermokarst” because a thermal change causes subsidence. This leads to a karst landscape, known for its erosion and sinkholes.

Turetsky said this is the first paper to pull together the wide body of literature on past and current abrupt thaw across different types of landscapes.

The authors then used this information along with a numerical model to project future abrupt thaw carbon losses. They found that thermokarst always involves flooding, inundation, or landslides. Intense rainfall events and the open, black landscapes that result from wildfires can speed up this dramatic process.

The researchers compared abrupt permafrost thaw carbon release to that of gradual permafrost thaw, trying to quantify a “known unknown.” There are general estimates of gradual thaw contributing to carbon emissions, but they had no idea how much of that would be caused by thermokarst.

They also wanted to find out how important this information would be to include in global climate models. At present, there are no climate models that incorporate thermokarst, and only a handful that consider permafrost thaw at all. While large-scale models over the past decade have tried to better account for feedback loops in the Arctic, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s most recent report only includes estimates of gradual permafrost thaw as an unresolved Earth system feedback.

“The impacts from abrupt thaw are not represented in any existing global model and our findings indicate that this could amplify the permafrost climate-carbon feedback by up to a factor of two, thereby exacerbating the problem of permissible emissions to stay below specific climate change targets,” said David Lawrence, of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and a coauthor of the study.

The findings bring new urgency to including permafrost in all types of climate models, along with implementing strong climate policy and mitigation, Turetsky added.

“We can definitely stave off the worst consequences of climate change if we act in the next decade,” said Turetsky. “We have clear evidence that policy is going to help the north and thus it’s going to help dictate our future climate.”

Other coauthors on the paper include researchers from the University of Guelph, Brigham Young University, the United States Geological Survey, University of Alaska Fairbanks, University of Alberta, Northern Arizona University, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, University of Potsdam, Stockholm University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Arctic permafrost thaw plays greater role in climate change than previously estimated

Carbon release through abrupt permafrost thaw

ABSTRACT: The permafrost zone is expected to be a substantial carbon source to the atmosphere, yet large-scale models currently only simulate gradual changes in seasonally thawed soil. Abrupt thaw will probably occur in <20% of the permafrost zone but could affect half of permafrost carbon through collapsing ground, rapid erosion and landslides. Here, we synthesize the best available information and develop inventory models to simulate abrupt thaw impacts on permafrost carbon balance. Emissions across 2.5 million km2 of abrupt thaw could provide a similar climate feedback as gradual thaw emissions from the entire 18 million km2 permafrost region under the warming projection of Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5. While models forecast that gradual thaw may lead to net ecosystem carbon uptake under projections of Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, abrupt thaw emissions are likely to offset this potential carbon sink. Active hillslope erosional features will occupy 3% of abrupt thaw terrain by 2300 but emit one-third of abrupt thaw carbon losses. Thaw lakes and wetlands are methane hot spots but their carbon release is partially offset by slowly regrowing vegetation. After considering abrupt thaw stabilization, lake drainage and soil carbon uptake by vegetation regrowth, we conclude that models considering only gradual permafrost thaw are substantially underestimating carbon emissions from thawing permafrost.