Fossil fuel divestment will increase carbon emissions, not lower them – “The divestment movement will simply force international oil companies to cede market share to national oil companies”

By Stefan Andreasson

25 November 2019

(The Conversation) – A global campaign encouraging individuals, organisations and institutional investors to sell off investments in fossil fuel companies is gathering pace. According to 350.org, US$11 trillion has already been divested worldwide.

But, while it may seem a logical strategy, divestment will not lower demand for fossil fuels, which is the key to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, it may even cause emissions to rise.

At first sight, the argument for divestment seems straightforward. Fossil fuel companies are the main contributors to the majority of CO2 emissions causing global warming. Twenty fossil fuel companies alone have contributed 35% of all energy-related carbon dioxide and methane emissions since 1965.

The argument goes that squeezing the flow of investment into fossil fuel companies will either bring their demise, or force them to drastically transform their business models. It makes sense for investors, too, as they avoid the risk of holding “stranded assets” – fossil fuel reserves that will become worthless as they can no longer be exploited. […]

While global demand for natural gas and oil is still rising, and investments are insufficient to meet future demand, divestment pressures are unlikely to impact the business plans of NOCs. As a result, instead of reducing global fossil fuel production, the divestment movement will simply force IOCs to cede market share to NOCs.

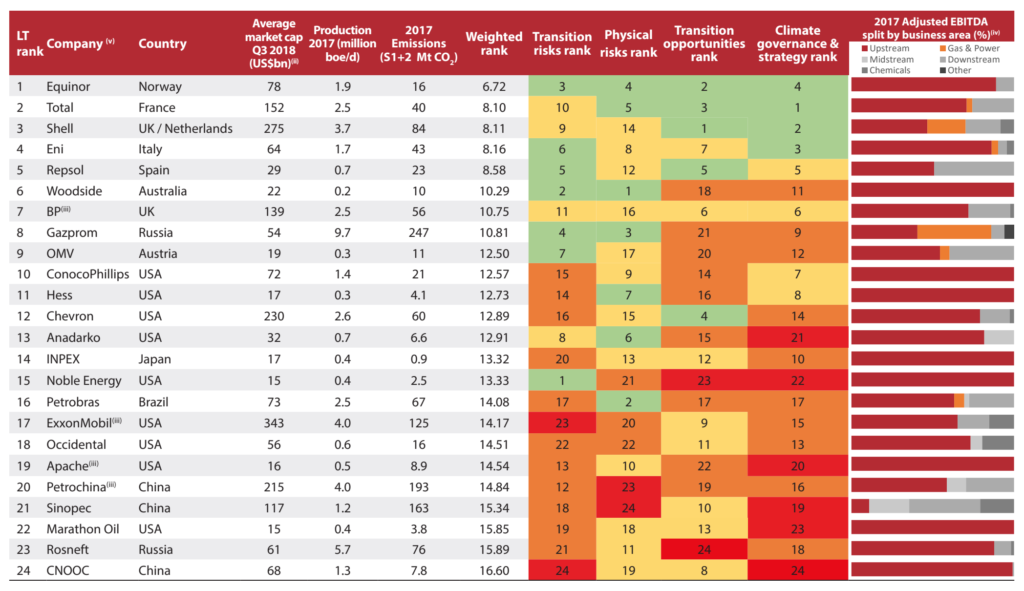

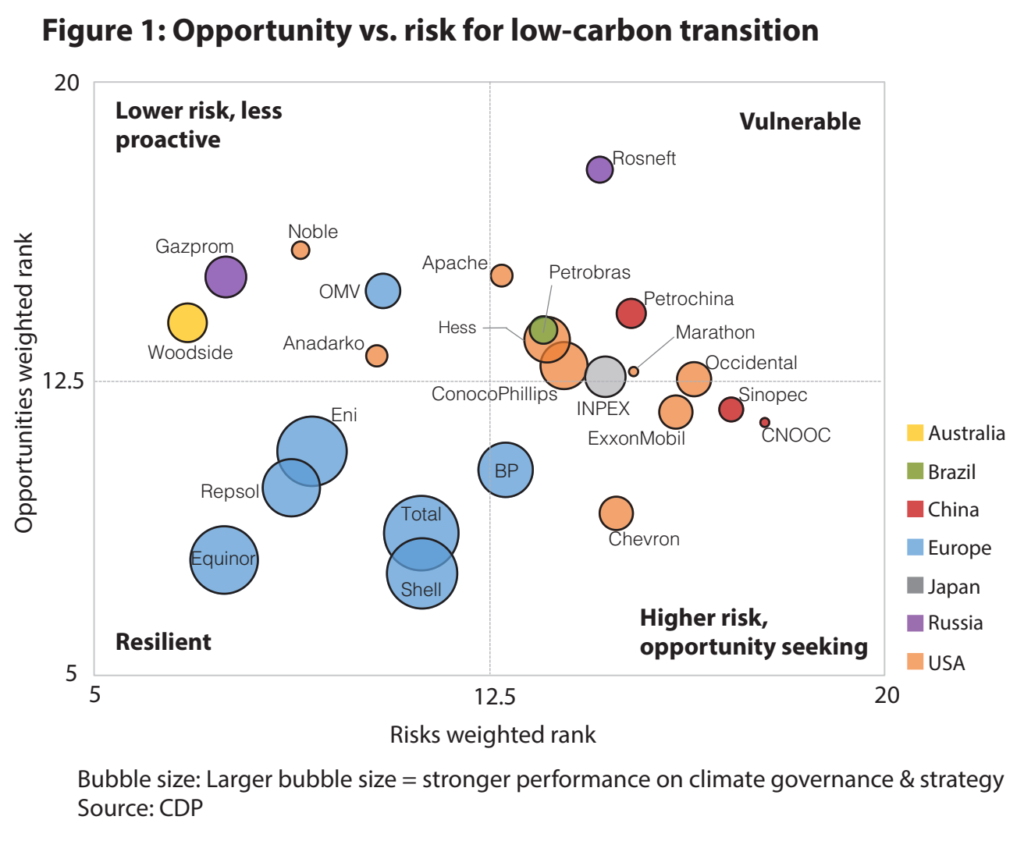

The primary targets of the divestment movement are international oil companies (IOCs) – private corporations that are headquartered in Western countries and listed on public stock exchanges. ExxonMobil, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, and Total are among the private oil “supermajors”.

Recent research suggests that divestment can reduce the flow of investment into these companies. But even if the divestment movement were successful in reducing the economic power of these companies, IOCs currently only produce about 10% of the world’s oil.

The rest is mostly produced by national oil companies (NOCs) – state-owned behemoths such as Saudi Aramco, National Iranian Oil Company, China National Petroleum Corporation and Petroleos de Venezuela, located mostly in low and middle income countries.

Given that NOCs are less transparent about their operations than are IOCs, and that many of them are also headquartered in authoritarian countries, they are less exposed to pressure from civil society. As a result, they are “dangerously under-scrutinised”, according to the Natural Resource Governance Institute.

As they are state-owned, they are also not directly exposed to pressure from shareholders. Even the imminent public listing of Saudi Aramco will only offer 1.5% of the company, and this will mainly come from domestic and emerging markets, which tend to impose much less pressure to value environmental issues. Environmental groups have urged Western multinational banks not to invest in the Saudi company.

This means that while global demand for natural gas and oil is still rising, and investments are insufficient to meet future demand, divestment pressures are unlikely to impact the business plans of NOCs. As a result, instead of reducing global fossil fuel production, the divestment movement will simply force IOCs to cede market share to NOCs.

If anything, this would cause CO2 emissions to rise. The carbon footprints of NOCs per unit of fuel produced are on average bigger than those of IOCs. [more]

Fossil fuel divestment will increase carbon emissions, not lower them – here’s why