Faded Texas oil field offers austerity lesson for U.S. shale – “There’s an inflection point coming here because production growth is going to slow down massively”

By Kevin Crowley

2 December 2019

(Bloomberg) – At EOG Resources Inc.’s Francisco lease in the heart of the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas, a half dozen cows laze in the shade of a tree next to black oil-storage tanks. A small flare burns atop a steel pylon, like a memorial to the boom days gone by.

There are six wells on the parcel of land — three drilled in 2013 and three from 2016 — and together they churn out just 130 barrels of crude daily, worth about $7,150 at current prices, according to data from ShaleProfile Analytics. Output is down more than 95% from peak levels, the data show.

Yet wells like these may be a harbinger of the U.S. shale industry’s future if investors are successful in forcing independent explorers to prize profits over production. In the wake of the oil price crash that began in 2014, new drilling in the Eagle Ford dwindled as management teams cut budgets, and output in the region is now down about 20% from pre-crash levels.

That austerity finally began to pay off this year as the Eagle Ford as a whole generated free cash flow for the first time, according to IHS Markit.

It’s a grand bargain that the Eagle Ford’s bigger Texas cousin — the Permian Basin — is wrestling with: sacrificing growth for profits.

At current oil prices, “what you cannot do is harvest cash and grow,” said Raoul LeBlanc, a Houston-based analyst at IHS. “There’s an inflection point coming here because production growth is going to slow down massively.”

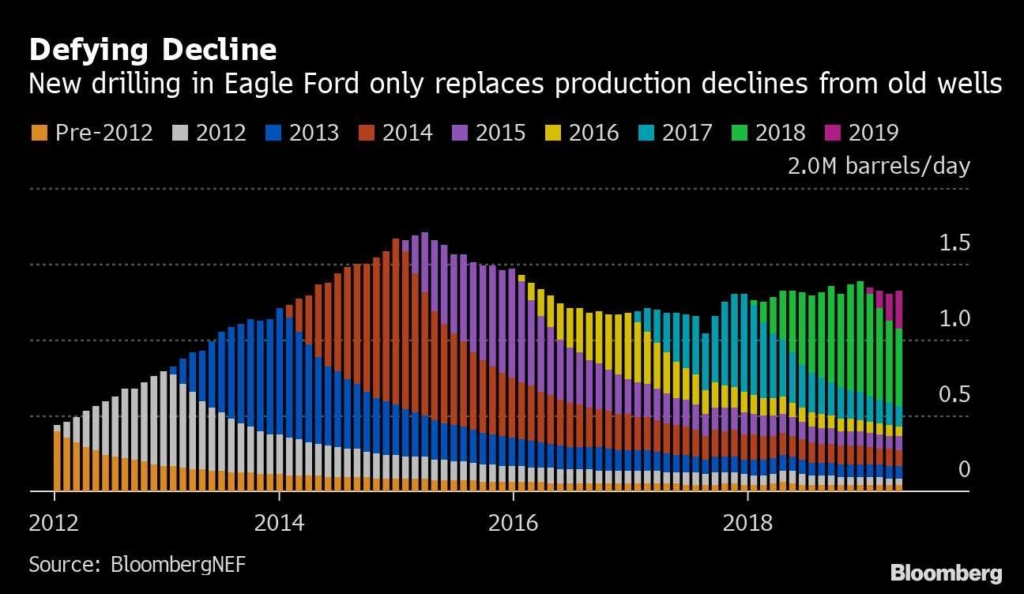

The implications for U.S. oil production are vast. Shale wells are gushers for the first three months but after that, output plummets so that by the end of the first year it’s down about 60%. That’s 10 times the decline rate of conventional wells.

Running To Stand Still

As a result, America’s record crude output relies heavily on new wells. About two-thirds of U.S. shale oil comes from wells drilled within the past 18 months, according to ShaleProfile’s data.

As the Eagle Ford shows, once new drilling slows, production quickly follows. Explorers in the South Texas field reduced drilling sharply in 2016, when oil cratered to less than $30 a barrel, and overall production has never fully recovered. The Eagle Ford now produces 1.37 million barrels a day, about 20% below its peak four years ago. [more]

Faded Texas Oil Field Offers Austerity Lesson for U.S. Shale