Drought, heat, and Victoria Falls: The spectre of hot drought

By Bob Henson

11 December 2019

(Weather Underground) – The massive curtain of water in southern Africa between Zambia and Zimbabwe known as Victoria Falls is the world’s biggest waterfall sequence when you take into account both width and height. Often ranked as one of the seven wonders of the natural world, the falls are a prime tourist destination, which explains much of the horrified reaction the last few days as news spread that the falls had dried to a virtual trickle.

Much of the coverage has centered on claims that the region is experiencing its worst drought in a century. The Zambezi River Basin that surrounds and nurtures the falls is a drought-prone place, a semiarid region accustomed to big year-to-year variations in rainfall. It’s typical for the falls to become starkly depleted in October and November, just before the onset of the summer wet season. Pictures of the falls as a raging torrent are more likely taken in March or April.

Oddly enough, there’s been no significant long-term decrease in annual average rainfall in the Zambezi Basin.

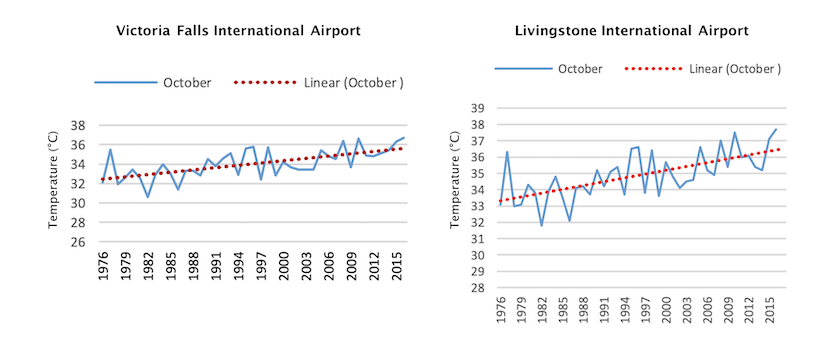

What’s happened this year is partially a story of a lack of rain—but just as much, it’s a tale of increased landscape-parching heat, combined with an increasingly delayed start to the region’s wet season. Both of these are long-term trends squarely in line with climate change, and they’re also frighteningly consistent with things happening on the other side of the world. […]

The spectre of hot drought

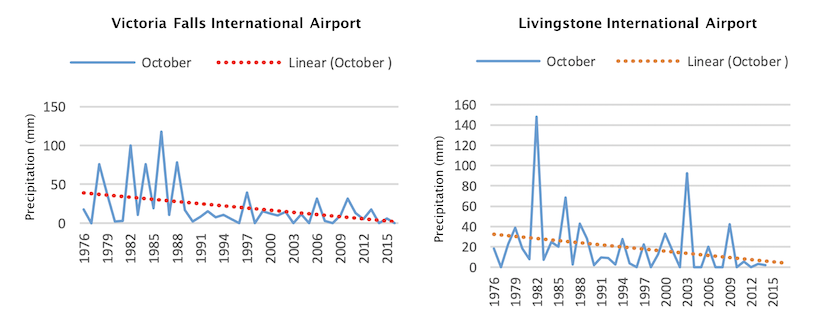

The most dramatic signals of a changing climate at Victoria Falls don’t emerge until you pull back the curtain and look at monthly trends.

In October and November, average rainfall has decreased at a startling rate. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Victoria Falls got at least 2 in (50 mm) of rain about every other October. Since 2000, the two wettest Octobers (2006 and 2010) produced only about half that amount. After an especially hot, dry summer, river flow at Victoria Falls in the last few weeks has dropped below the 45-year record low set in 1995, according to Dube. Water levels at the Kariba Dam have dropped to their lowest levels since 1996. [more]

Drought, Heat, and Victoria Falls: A Climate Story with a Twist