Historic Australia drought steals lives of a generation crying for action – “This is a direct impact of climate change. I don’t care what anybody says.”

By Tom McIlroy

4 October 2019

Stanthorpe, Queensland (Financial Review) – The dirt underfoot as dry as anyone can remember, Mike Hayes sees numbers everywhere as he walks through dusty rows of grapevines.

A celebrated winemaker in Queensland’s Granite Belt region, he crunches rainfall data in his head, trying not to consider the worst.

“In the past we frequently have had a good solid 60 per cent of our rainfall in spring and summer,” he tells AFR Weekend.

“We’d usually get between 730 and 780 mils annually. I think we’ve had 154 millimetres of rain to date for this calendar year, so we’re way behind.

“Even the driest year, back in the 1930s, was 358 millimetres, so we need an awful lot of rain to catch up to even match that by Christmas.”

South-west of Brisbane, Hayes works on about 260 acres (105 hectares), now completely out of water. The business is one of thousands trapped in entrenched drought across much of eastern Australia, with many preparing for drastic action to survive.

“I’ve gone back to old-style farming,” Hayes says. “It’s digging up between the rows, removing all of the weeds, reducing the bud numbers on the vines to lower the crop load and waiting for the God pump to kick in.

“That’s Mother Nature and rainfall arriving.”

It’s not a normal event. If we farmed like our forefathers did, we would have been broke years ago.

Peter Mailler, Australia farmer, on the historic drought in New South Wales

Like so many others working on or around the land while 95 per cent of NSW and two-thirds of Queensland is in long-running drought, Hayes says he’s in “survival mode”.

“I’m trying to have the glass at 55 per cent full but probably deep down I know if I don’t get sufficient rainfall over the next four to five weeks … we may have an 80 to 100 per cent loss for the vintage this year.”

Seen it all before

To say Hayes is unimpressed with news of a regional drought tour by federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg and senior Coalition MPs this week would be an understatement.

Alongside Nationals minister David Littleproud, Frydenberg visited Stanthorpe and Warwick in Queensland, and Inverell in northern NSW, hearing first-hand how primary producers, businesses and community leaders are holding up.

Hayes has seen it all before.

“They’ll come in their flash RM Williams and their Akubras and their imported polo shirts from France, thinking they’re super cool.

“I’d like to get them out in the vineyard and spend a couple of days working, tasting and eating the dust, facing extreme temperatures we haven’t seen before. It might just wake a few of these politicians up.”

He’s not exaggerating. The most recent drought analysis by the Bureau of Meteorology shows rainfall remains painfully below average in the eastern states, as well as in South Australia and parts of northern Tasmania.

A total lack of meaningful rainfall has persisted and root zone soil moisture is well below average for most of the country.

The tour has included stops at bone-dry paddocks, struggling businesses and the federally funded Emu Swamp Dam project in south-east Queensland.

At every stop, locals tell the city visitors more financial assistance is badly needed. The Coalition has a $7 billion drought package, and last week announced another $100 million in funding, which included extending and simplifying the farm household allowance, a welfare payment some farmers have been reluctant to take up.

More than 100 local councils will receive $1 million grants and money is going to low-interest loans, non-profits and financial counselling services.

For Mike Hayes, the entire federal budget won’t be enough if the Coalition keeps avoiding the existential elephant in the room.

“This is a direct impact of climate change. I don’t care what anybody says. The sceptics will still argue but we’re seeing later winters; we’re seeing irregular frosts right into November because we’re so high up, and we get the bud bursts early.

“The climate and the weather is definitely changing, and getting crazy.”

‘An unprecedent situation’

More than two hours’ drive inland at Goondiwindi, grain and cattle farmer Peter Mailler agrees.

“We’re enduring what is essentially an unprecedented situation,” he says.

“If you look at rainfall you can see it has been dry before, and that’s right, but you couple the rainfall totals that we’ve got in the past 12 months and then overlay it with the temperature, we really are in uncharted waters for what we’re trying to deal with.

“For as long as they fail to link the future and a drought policy or an extreme weather events policy to the science, and what we understand about the likely impacts of a changing climate and increasing intensity and frequency of these events, we’re all on a hiding to nothing.”

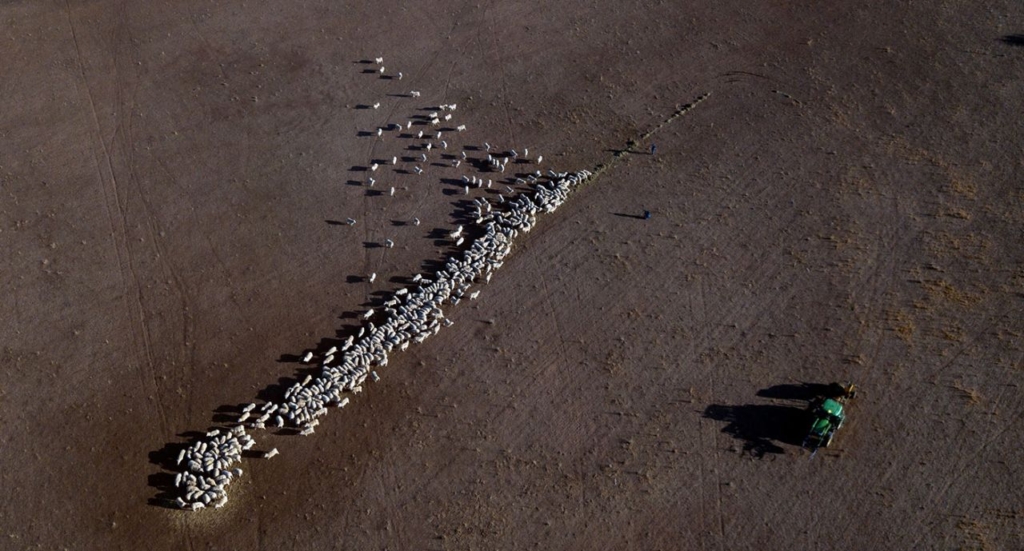

After years of drought, Australia’s agriculture sector is growing smaller along with the amount of land used for primary production.

Bureau of Statistics data show there were 85,000 agricultural businesses in Australia at the start of the financial year, a drop of 3 per cent from June 2017.

As farmers say each successive year of drought gets harder, about 378 million hectares of land is being used for agriculture in Australia, a drop of 4 per cent in two years.

Some 85 per cent of farm income comes from production, with 11 per cent from off-farm employment or other business, and 0.6 per cent from grants, government transfers and relief funding.

We accept the science around climate change. We accept that it is part of what is happening here today. We’ve had droughts in the past in this nation, very severe ones … droughts are not new, but the severity of this drought is the worst in living memory and we do accept that the climate is changing and man is contributing to that. The science has told us that.

Josh Frydenberg, Treasurer of Australia

So far, just over a third of eligible households are accessing the expanded farm household allowance payment, a signal the clunky application process and pride could be getting in the way of immediate financial support.

Frydenberg stressed dollars and data during his visit but conceded he was in the region to listen to ideas for future assistance by the government.

He has been visibly moved by the stories locals have told him, including farms going to the wall and another three suicides in one small area in recent months.

‘It’s not a normal event’

Like so many others, Peter Mailler is thinking about both immediate help and longer-term planning.

“At some point you must recognise that what we’re dealing with is not able to be mitigated through normal strategies.

“It’s not a normal event. If we farmed like our forefathers did, we would have been broke years ago.”

His family crops about 6000 acres (2400 hectares) of cereals and pulses and is looking after stud cattle after downsizing their stock. Despite years without good rain, they only had to buy in fodder for the first time two months ago.

“I’m a little bit circumspect about the situation that we’re in and the language and the political rhetoric,” he says.

“There’s a lot of people doing things to be seen to be doing things without actually ever doing anything. The window dressing and positioning around drought and drought policy in Australia is actually startling.”

Only good fortune is helping his farm get through 2019, he says.

Nationals member for New England Barnaby Joyce, left. Treasurer Josh Frydenberg and Drought Minister David Littleproud at Byron Station north of Inverell in northern NSW. AAP

“We were lucky to get under a single fall of rain in March that made the difference but there are better farmers than me who have done everything right, who will make significant losses this year, just because they weren’t lucky enough to be on the edge of a storm.”

Across the border in Inverell, off-farm realities are changing because of drought. In November, the Target store will close, a signal local cafe owner Jenny Thomas dreads.

“Since we heard that, the morale has dropped a bit again,” she said.

“In small towns you have Target, you have Big W. People to come to town for them. They want basics – bras, socks and undies – then they’ll go to the boutiquey shops for the nice things.”

So far her Freckles Cafe business is holding up. Thomas works seven days herself and says locals are still finding the money for a cup of coffee.

The children work hard to help us, instead of doing homework or downtime.

Letter from a farming family struggling with the historic Australia drought in Inverell, New South Wales

“It’s a hard slog already. The spend is down. The foot traffic is still coming in but they’re not spending as much and they might not come in once every fortnight. I might see them once every three months now.”

With a cheerful smile, she says the state and federal governments should focus on nickel and dime ways to help struggling communities.

“I thought opening a cafe five-and-a-half years ago was a good idea but it’s very stressful.”

More frequent and severe

Economists say over the past 50 years, Australia’s real gross farm product has declined by about 27.5 per cent during droughts, with leaner production methods and technology helping create a smaller decline in agricultural output during the current dry.

Improved weather forecasting and irrigation also help but droughts are becoming more frequent and more severe in Australia.

Trade figures released on Thursday showed strong beef exports, as producers turn off more stock because of the dry. Wheat exports were down, at about $213 million, in August – the third-worst result for the month in the past two decades. The only two worse totals were both in periods of drought.

At each stop on the tour, Frydenberg has faced questions about the lack of a co-ordinated national drought policy. Labor has asked the Auditor-General to probe the veracity of the claimed $7 billion price tag for spending from Canberra.

The Treasurer sees no disconnect between the government’s policies on drought and effective action to mitigate damaging climate change, stressing Australia’s role in the global community.

“We accept the science around climate change. We accept that it is part of what is happening here today.

“We’ve had droughts in the past in this nation, very severe ones … droughts are not new, but the severity of this drought is the worst in living memory and we do accept that the climate is changing and man is contributing to that. The science has told us that.”

Imminent exhaustion of water

For Stanthorpe, which faced serious bushfires just weeks ago, more immediate problems persist. Facing the imminent exhaustion of its water supply, about $800,000 per month is going to be spent to truck in 34 truckloads of water per day.

At times, the emotional impact of the situation here has shown on Frydenberg’s face. A long way from inner-city Kooyong, the message has been received.

He read letters written by struggling families in Inverell and was visibly moved by stories about what the lack of rain has done to everyday life.

One letter said the loss of time had been the hardest thing.

“Time to do what we used to do before carting feed and water took over,” the Treasurer read.

“We used to enjoy riding our horses and going places but now we cannot go anywhere. As soon as we do, a cow will get stuck in the mud that used to be a dam. The horses, who are part of our family, look at us every day for more food.

“The children work hard to help us, instead of doing homework or downtime. Time would have to be the greatest impact.”

With time stolen everywhere here, the endless wait for rain drags on.