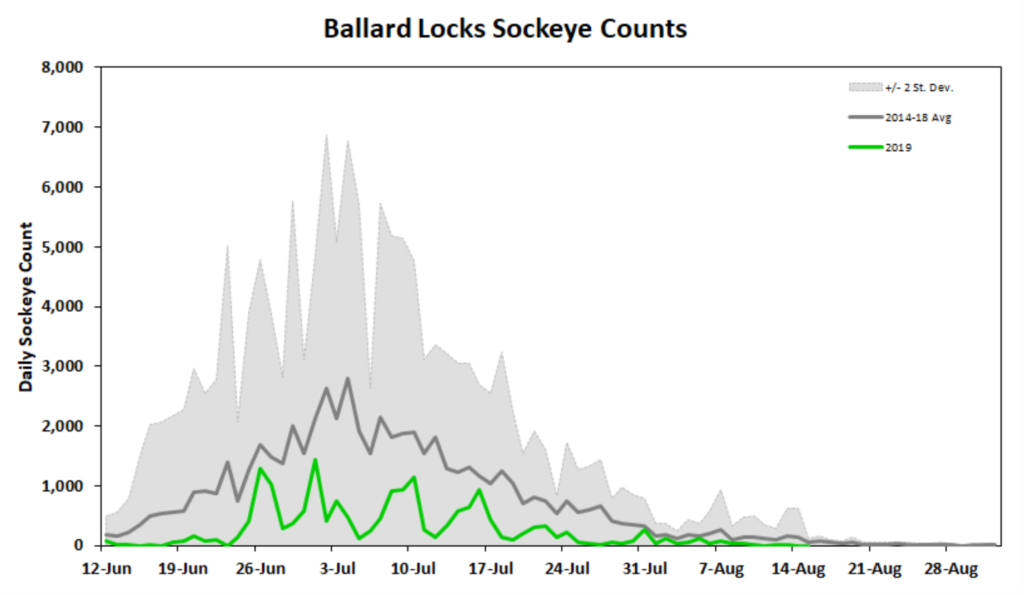

Lowest sockeye salmon count on record at the Ballard Locks – “The salmon population is just not healthy anymore”

By Meghan Walker

15 August 2019

(My Ballard) – The number of sockeye salmon passing through the Ballard Locks Fish Ladder is at all-time low, according to yearly counts dating back to the 1970s.

According to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s daily count, just 18,000 sockeye have been counted at the fish ladder during their upstream migration this summer.

Aaron Bosworth, a fish biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, says it’s cause for concern. “This is the lowest sockeye count ever recorded at the Locks,” Bosworth says, and it’s been trending this way for the past few years.

He says there are a couple of factors at play.

One of the major issues is juvenile predation. Sockeyes spend about a year in Lake Washington before they head out to sea, and during this time, their numbers drop significantly due to predation.

Of several million fry that make their into the lake every late winter/early spring, just a tiny percentage make it out to sea through the Ballard Locks. Bosworth describes Lake Washington as a “bottleneck to their survival”, saying he believes warmer lake temperatures are a factor.

“The lake warms up sooner and stays warm longer, so that makes all non-native fish more hungry,” he says. Another factor leading to higher predation is light pollution: skyglow means predators are better able to hunt at night. […]

The sockeye decline is expected to continue — Bosworth says that one model estimates they could disappear altogether in 40 years.

There are some ecosystem impacts, including a reduced amount of nutrient exchange in the Cedar River watershed. However, the larger impact is social.

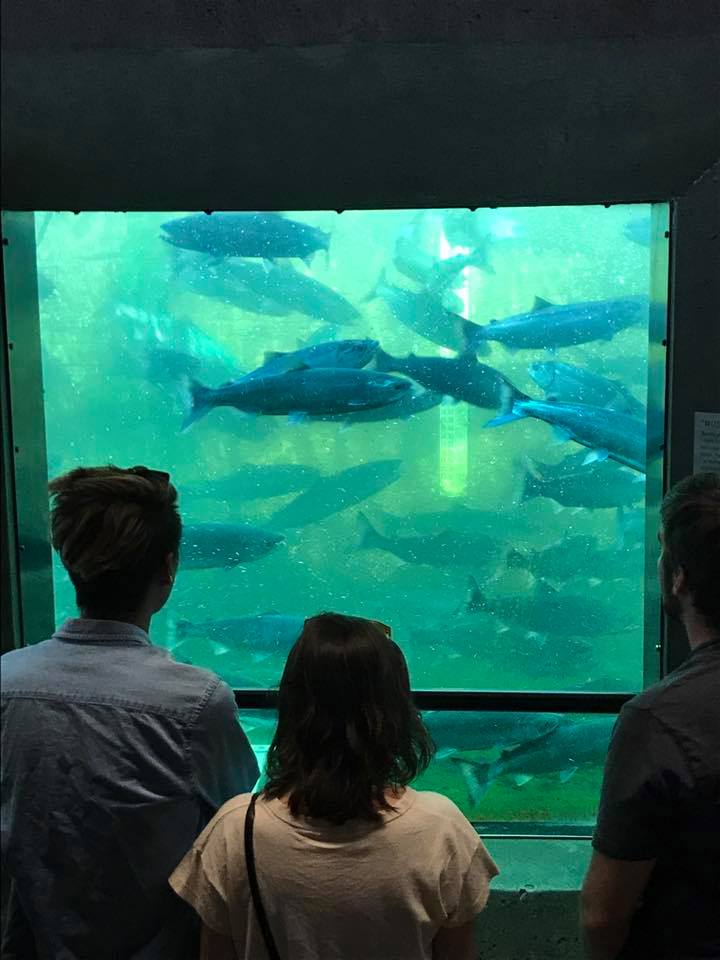

“People want sockeye to be here and in Lake Washington. It’s remarkable to have a run of salmon,” Bosworth says.

“But the salmon population is just not healthy anymore.” [more]

Lowest sockeye salmon count in 40 years at the Ballard Locks