Pesticide exposure causes bumblebee flight to fall short – “The negative effects of pesticide exposure on flight endurance have the potential to reduce the area that colonies can forage for food”

By Hayley Dunning

30 April 2019

(Imperial College London) – Bees exposed to a neonicotinoid pesticide fly only a third of the distance that unexposed bees are able to achieve.

Flight behaviour is crucial for determining how bees forage, so reduced flight performance from pesticide exposure could lead to colonies going hungry and pollination services being impacted.

Foraging bees are essential pollinators for the crops we eat and the wildflowers in our countryside, gardens and parks. Any factor compromising bee flight performance could therefore impact this pollination service.

Previous studies from our group and others have shown that bee foragers exposed to neonicotinoid pesticides bring back less food to the colony. Our study on flight performance under pesticide exposure provides a potential mechanism to explain these findings

Dr Richard Gill, Senior Lecturer, Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London

A study by Imperial College London researchers, published today in the journal Ecology and Evolution, reveals how exposure to a common class of neurotoxic pesticide, a neonicotinoid, reduces individual flight endurance (distance and duration) in bumblebees.

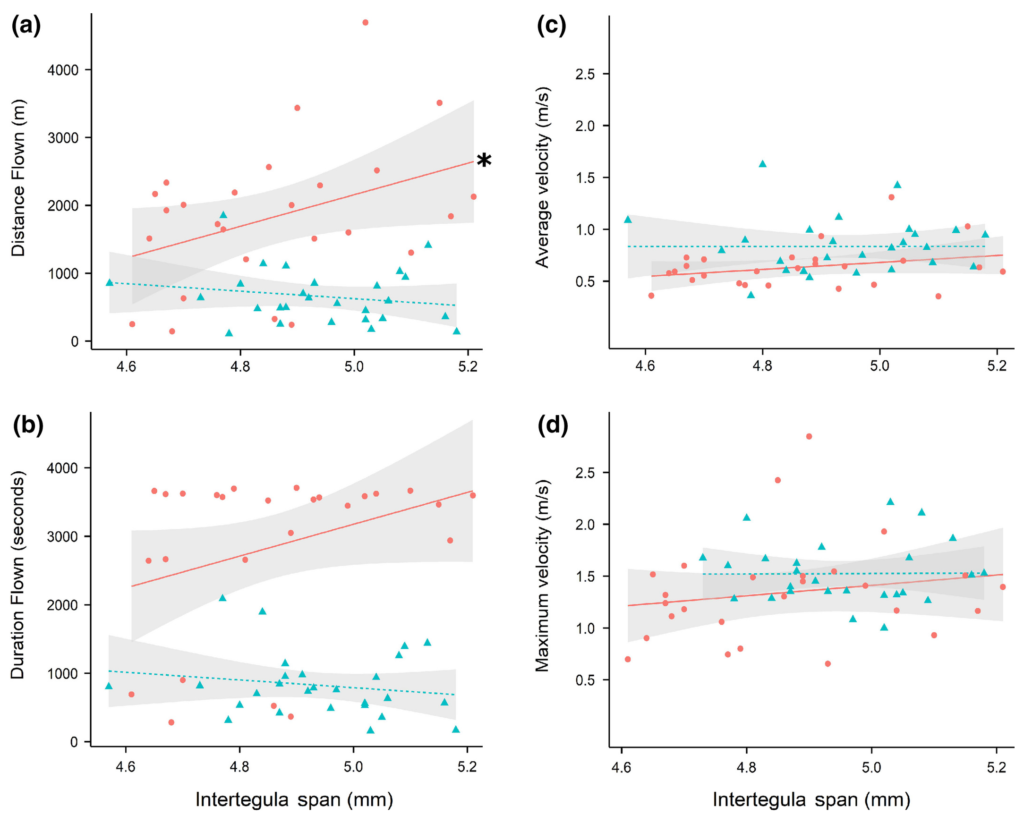

The study shows that bees exposed to the neonicotinoid imidacloprid in doses they would encounter in fields fly significantly shorter distances and for less time than bees not exposed, which could reduce the area in which colonies can forage for food by up to 80 percent.

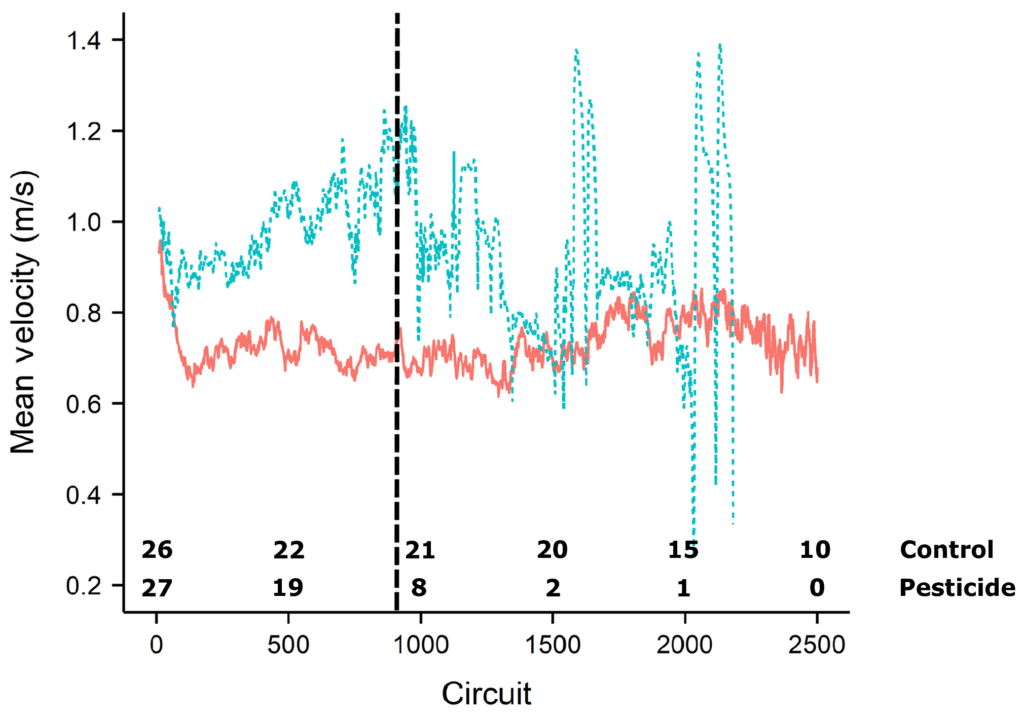

Intriguingly, exposed bees seemed to enter a hyperactive-like state in which they initially flew faster than unexposed bees and therefore may have ‘worn themselves out’.

The Tortoise and the Hare

First author of the study Daniel Kenna, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: “Neonicotinoids are similar to nicotine in the way they stimulate neurons, and so a ‘rush’ or hyperactive burst of activity does make sense. However, our results suggest there may be a cost to this initial rapid flight, potentially through increased energy expenditure or a lack of motivation, in the form of reduced flight endurance.

“Our findings take on an interesting parallel to the story of the ‘Tortoise and the Hare’. As the famous fable states, ‘slow and steady wins the race’. Little did Aesop know that this motto may be true for bumblebees in agricultural landscapes. Just like the Hare, being speedier does not always mean you reach your goal quicker, and in the case of bumblebees, exposure to neonicotinoids may provide a hyperactive ‘buzz’ but ultimately impair individual endurance.”

The team tested the bees’ flight using an experimental ‘flight mill’ – a spinning apparatus with long arms connected to magnets. The bees had a small metal disc attached to their backs, which allowed the researchers to attach bees temporarily to the magnetic arm. As the bees flew in circles, the team were able to accurately measure how far they flew and how fast under a controlled environment.

Lead author Dr Richard Gill, also from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, commented: “Previous studies from our group and others have shown that bee foragers exposed to neonicotinoid pesticides bring back less food to the colony. Our study on flight performance under pesticide exposure provides a potential mechanism to explain these findings.

“The negative effects of pesticide exposure on flight endurance have the potential to reduce the area that colonies can forage for food. Exposed foraging bees may find themselves unable to reach previously accessible resources, or incapable of returning to the nest following exposure to contaminated flowers.

“Not only could this reduce the abundance, diversity, and nutritional quality of food available to a colony affecting its development, but it could also limit the pollination service bees provide.”

Pesticide exposure causes bumblebee flight to fall short

Pesticide exposure affects flight dynamics and reduces flight endurance in bumblebees

ABSTRACT: The emergence of agricultural land use change creates a number of challenges that insect pollinators, such as eusocial bees, must overcome. Resultant fragmentation and loss of suitable foraging habitats, combined with pesticide exposure, may increase demands on foraging, specifically the ability to collect or reach sufficient resources under such stress. Understanding effects that pesticides have on flight performance is therefore vital if we are to assess colony success in these changing landscapes. Neonicotinoids are one of the most widely used classes of pesticide across the globe, and exposure to bees has been associated with reduced foraging efficiency and homing ability. One explanation for these effects could be that elements of flight are being affected, but apart from a couple of studies on the honeybee (Apis mellifera), this has scarcely been tested. Here, we used flight mills to investigate how exposure to a field realistic (10 ppb) acute dose of imidacloprid affected flight performance of a wild insect pollinator—the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris audax. Intriguingly, observations showed exposed workers flew at a significantly higher velocity over the first ¾ km of flight. This apparent hyperactivity, however, may have a cost because exposed workers showed reduced flight distance and duration to around a third of what control workers were capable of achieving. Given that bumblebees are central place foragers, impairment to flight endurance could translate to a decline in potential forage area, decreasing the abundance, diversity, and nutritional quality of available food, while potentially diminishing pollination service capabilities.

Pesticide exposure affects flight dynamics and reduces flight endurance in bumblebees