Humanity’s climate “carbon budget” dwindling fast – At current CO2 emission rates the budget will be exhausted in less than 14 years – “The trillion-dollar question is how much of a carbon budget do we have left?”

17 July 2019 (AFP) – The concept of a carbon budget is dead simple: figure out how much CO2 humanity can pump into the atmosphere without pushing Earth’s surface temperature beyond a dangerous threshold. [cf. What Counts for Our Climate: Carbon Budgets Untangled and Budgeting for our future climate. –Des]

The 2015 Paris climate treaty enjoins the world to set that bar at “well below” two degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) in order to avoid an upsurge in killer heatwaves, droughts and superstorms made more destructive by rising seas.

Last year, the UN’s climate science body concluded this already hard-to-reach goal may not be ambitious enough.

Only a 1.5C cap above pre-industrial levels, for example, could prevent the total loss of coral reefs that anchor a quarter of marine life and coastal communities around the globe, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said in a landmark report.

But calculating exactly how much CO2 — produced mainly by burning fossil fuels but also deforestation — we can emit without busting through either of these limits has been deceptively hard to calculate.

Indeed, scientific estimates over the last few years have differed sharply, sometimes by a factor of two or three.

“The unexplained variations between published estimates have resulted in a lot of confusion,” Joeri Rogelj, a lecturer at Imperial College London, told AFP.

Starting in 2019 will require a mitigation rate of about five percent per year for a two-thirds chance of staying below 2C.

Robbie Andrew, an economist at the CICERO Centre for International Climate Research

To help clear up that muddle, Rogelj and colleagues set out to solve the carbon budget puzzle — or at least make sure that everyone is reading from the same page.

This seemingly academic exercise, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, has huge real-world repercussions.

“The trillion-dollar question is how much of a carbon budget do we have left?”, Rogelj said.

About 580 billion tonnes, or gigatonnes (Gt), of CO2, if we’re willing to settle for a 50 percent chance of capping global warming at 1.5C, according to the October IPCC report, for which Rogelj was a coordinating lead author.

At current CO2 emission rates — 2018 saw a record 41.5 Gt — that budget would be exhausted in less than 14 years. […]

Even a 2C cap remains a huge challenge and may slip beyond our grasp if carbon pollution continues its upward trend.

Robbie Andrew, an economist at the CICERO Centre for International Climate Research in Norway, has done calculations to show how crucial it is for emissions to begin a downward trajectory as soon as possible.

If carbon pollution had peaked in 2000, an average annual decline of two percent would have kept Earth under the 2C threshold. Tough, but doable.

“Starting in 2019 will require a mitigation rate of about five percent per year for a two-thirds chance of staying below 2C,” Andrew noted in a blog entry.

Given that GDP growth and greenhouse gas emissions have mostly moved in lockstep, it is hard to imagine such a sharp, sustained drop without a global economy in freefall.

Another study earlier this month highlighted yet another source of pressure on carbon budgets.

If existing power plants and other fossil-fuel burning equipment operate to the end of their expected lifespan, researchers reported in Nature, they will emit more than 650 Gt CO2 — exploding the 1.5C budget.

Nor does that total take into account dozens of large-scale coal- and gas-burning power plants under construction or in the pipeline around the world, with industry giants forecasting more build up of fossil fuel infrastructure in the coming decades. [more]

Humanity’s climate ‘carbon budget’ dwindling fast

Estimating and tracking the remaining carbon budget for stringent climate targets

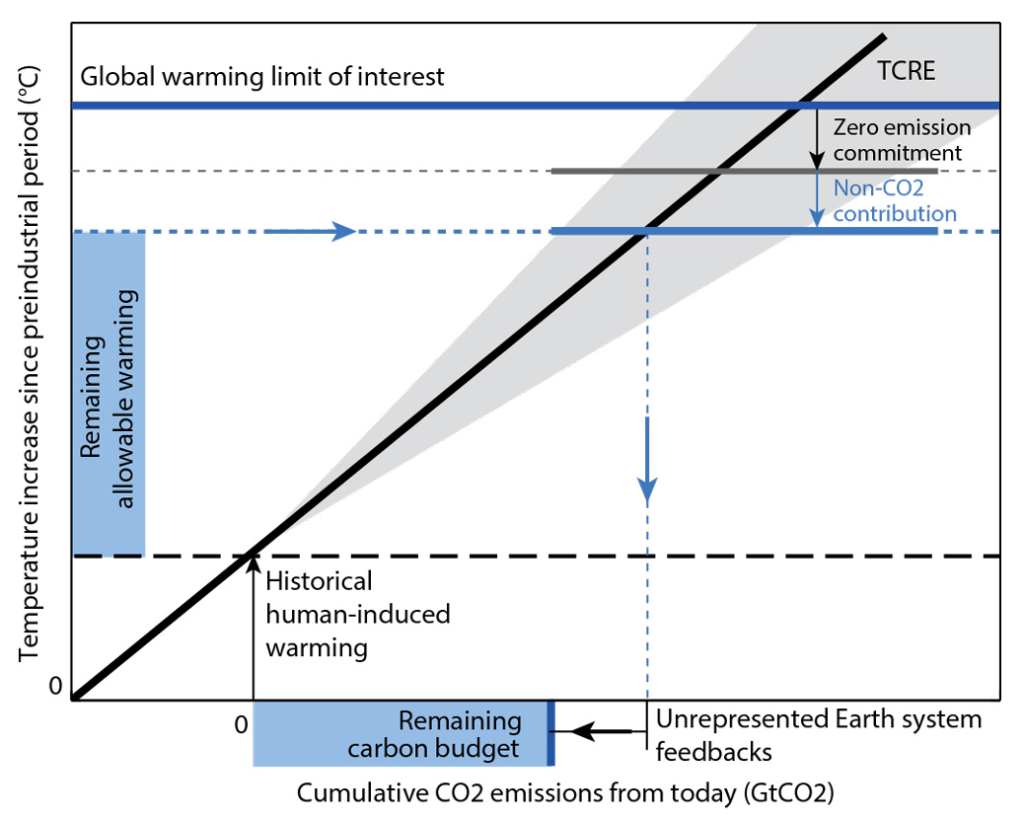

ABSTRACT: Research reported during the past decade has shown that global warming is roughly proportional to the total amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. This makes it possible to estimate the remaining carbon budget: the total amount of anthropogenic carbon dioxide that can still be emitted into the atmosphere while holding the global average temperature increase to the limit set by the Paris Agreement. However, a wide range of estimates for the remaining carbon budget has been reported, reducing the effectiveness of the remaining carbon budget as a means of setting emission reduction targets that are consistent with the Paris Agreement. Here we present a framework that enables us to track estimates of the remaining carbon budget and to understand how these estimates can improve over time as scientific knowledge advances. We propose that application of this framework may help to reconcile differences between estimates of the remaining carbon budget and may provide a basis for reducing uncertainty in the range of future estimates.

Estimating and tracking the remaining carbon budget for stringent climate targets