U.S. environment agency cuts funding for kids’ health studies – “It works out perfectly for industry”

By Sara Reardon

13 May 2019

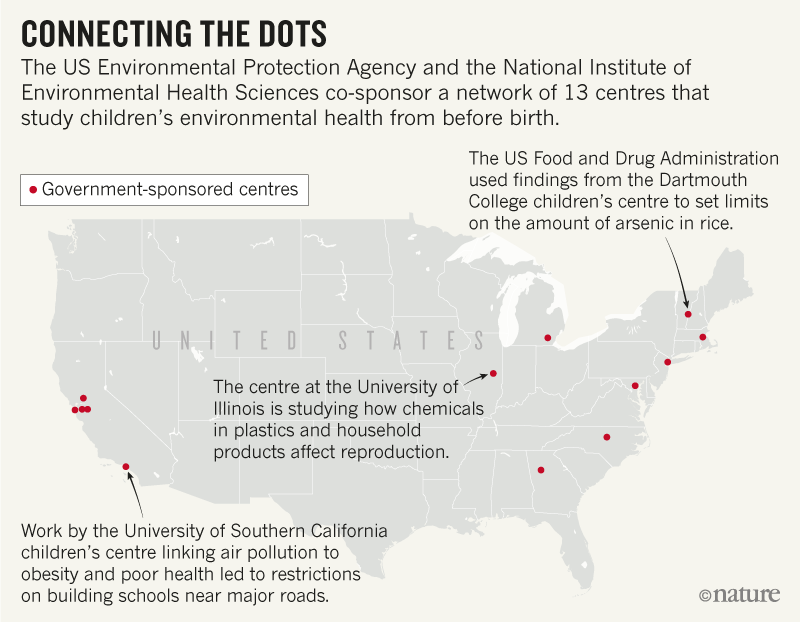

(Nature) – The Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health has tracked the lives of hundreds of children in New York City since 1998. Scientists have collected samples of blood, urine and even the air in children’s homes, starting when their subjects were in the womb, to tease out the health effects of chemicals and pollutants. The centre’s findings influenced New York City’s decision in 2018 to phase out diesel buses, and its staff members teach schools and community groups about the harmful chemicals and pollution that kids encounter each day.

Now, the future of the Columbia facility and a dozen like it is in doubt. Their last grants from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which has provided half of the centres’ funding for two decades, will expire in July — and the agency has decided that it will not renew its support for the facilities.

The programme’s other government sponsor, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) says that it cannot replace the funding that the EPA has historically provided. Scientists at the children’s centres are increasingly worried that the EPA’s withdrawal will force them to shut down decades-long research projects.

Studies of this length are rare and valuable, because they can reveal associations between environmental exposures early in life and health problems years later. And the mix of threats that kids face changes over time. “Twenty years ago, what we were studying is not the same as what we’re studying today,” says Ruth Etzel, a paediatrician at the EPA who specializes in children’s environmental health. “We have to study children now, in their communities.”

Many environmental-health researchers see the EPA’s decision to cut funding for the children’s centres as part of a push by President Donald Trump’s administration to undermine science at the agency, which is responsible for the safety of US air and water. “It works out perfectly for industry,” says Tracey Woodruff, who runs the children’s centre at the University of California, San Francisco. When weighing the harms of a chemical against its benefits, she says, “if EPA doesn’t know, it counts for zero”.

The EPA did not respond to multiple requests for comment on its plans for the children’s centres, or on its work on children’s environmental health more generally. […]

Linda McCauley, an environmental-health researcher at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, who leads the children’s centre there, thinks that the EPA’s personnel moves were designed to benefit the chemical industry, by stymieing research that could suggest the need for new or tougher regulations. “That’s how this administration is working,” she says. “They can be effective by slowing things down to a crawl.” [more]