The methane detectives: On the trail of a global warming mystery – “The bottom line is that methane is going up and doesn’t look like it will stop anytime soon”

By Jonathan Mingle

13 May 2019

(Undark) – Every week, dozens of metal flasks arrive at NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, each one loaded with air from a distant corner of the world.

Research chemist Ed Dlugokencky and his colleagues in the Global Monitoring Division catalog the canisters, and then use a series of high-precision tools — a gas chromatograph, a flame ionization detector, sophisticated software — to measure how much carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane each flask contains.

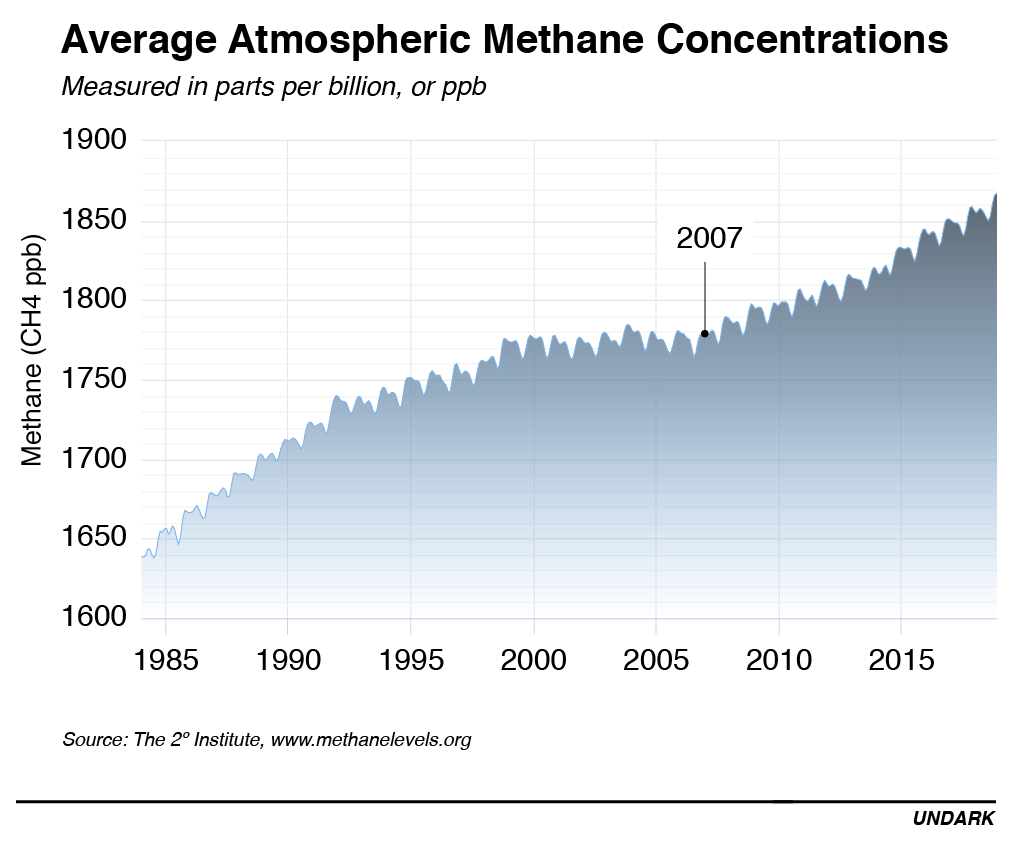

These air samples — collected at observatories in Hawaii, Alaska, American Samoa, and Antarctica, and from tall towers, small aircraft, and volunteers on every continent — have been coming to Boulder for more than four decades, as part of one of the world’s longest-running greenhouse gas monitoring programs. The air in the flasks shows that the concentration of methane in the atmosphere had been steadily rising since 1983, before levelling off around 2000. “And then, boom, look at how it changes here,” Dlugokencky says, pointing at a graph on his computer screen. “This is really an abrupt change in the global methane budget, starting around 2007.”

The amount of methane in the atmosphere has been increasing ever since. And nobody really knows why. What’s more, no one saw it coming. Methane levels have been climbing more steeply than climate experts anticipated, to a degree “so unexpected that it was not considered in pathway models preparatory to the Paris Agreement,” as Dlugokencky and several co-authors noted in a recently published paper.

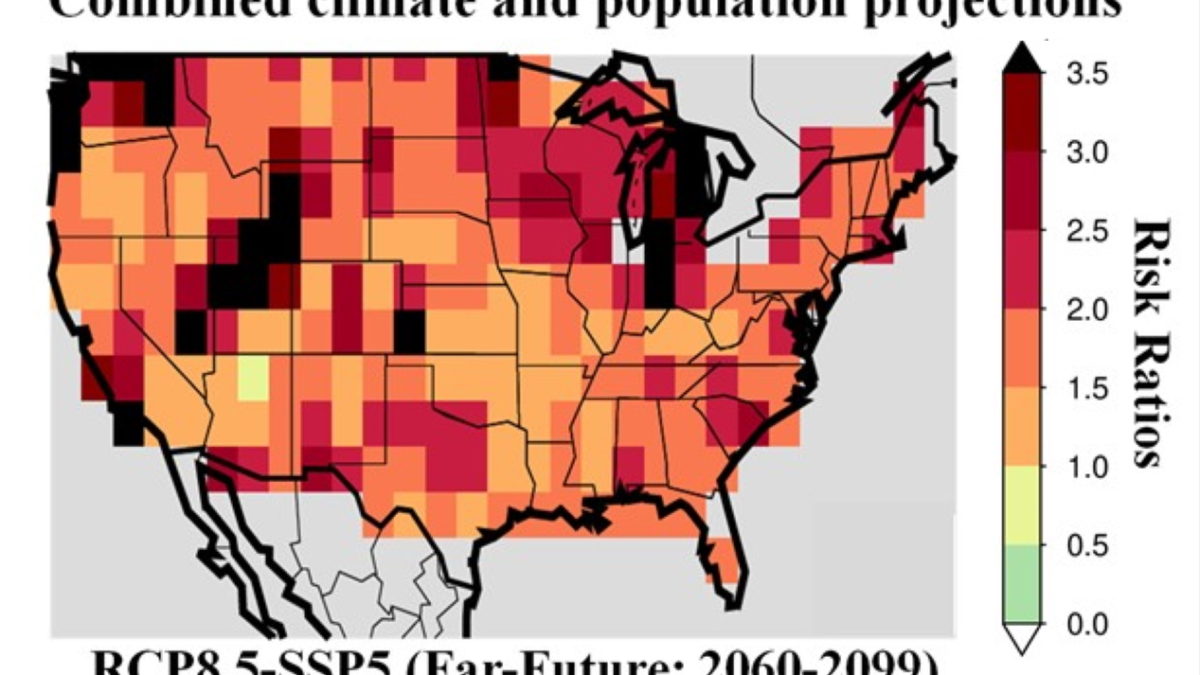

As the years plod on and the methane piles up, solving this mystery has taken on increasing urgency. Over a 20-year-time frame, methane traps 86 times as much heat in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. It is responsible for about a quarter of total atmospheric warming to date. And while the steady increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide are deeply worrying, they are at least conforming to scientists’ expectations. Methane is not. Methane — arguably humanity’s earliest signature on the climate — is the wild card. […]

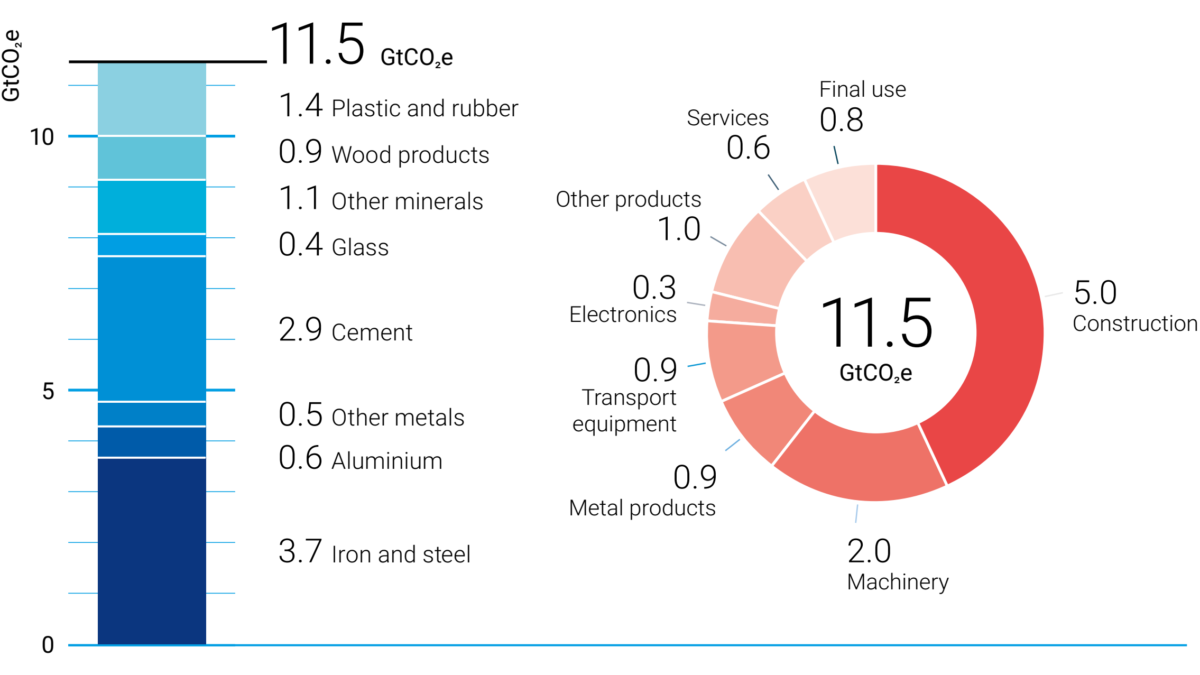

Some researchers, such as Robert Howarth of Cornell, remain convinced that fugitive emissions from oil and gas production — especially fracking — are systematically underestimated, and likely to be behind the global spike. “It’s a compelling narrative,” says Pep Canadell, executive director of the Global Carbon Project, “but the larger community does not support that view.” […]

“The bottom line,” says Canadell, “is that methane is going up, and doesn’t look like it will stop anytime soon.” [more]

The Methane Detectives: On the Trail of a Global Warming Mystery

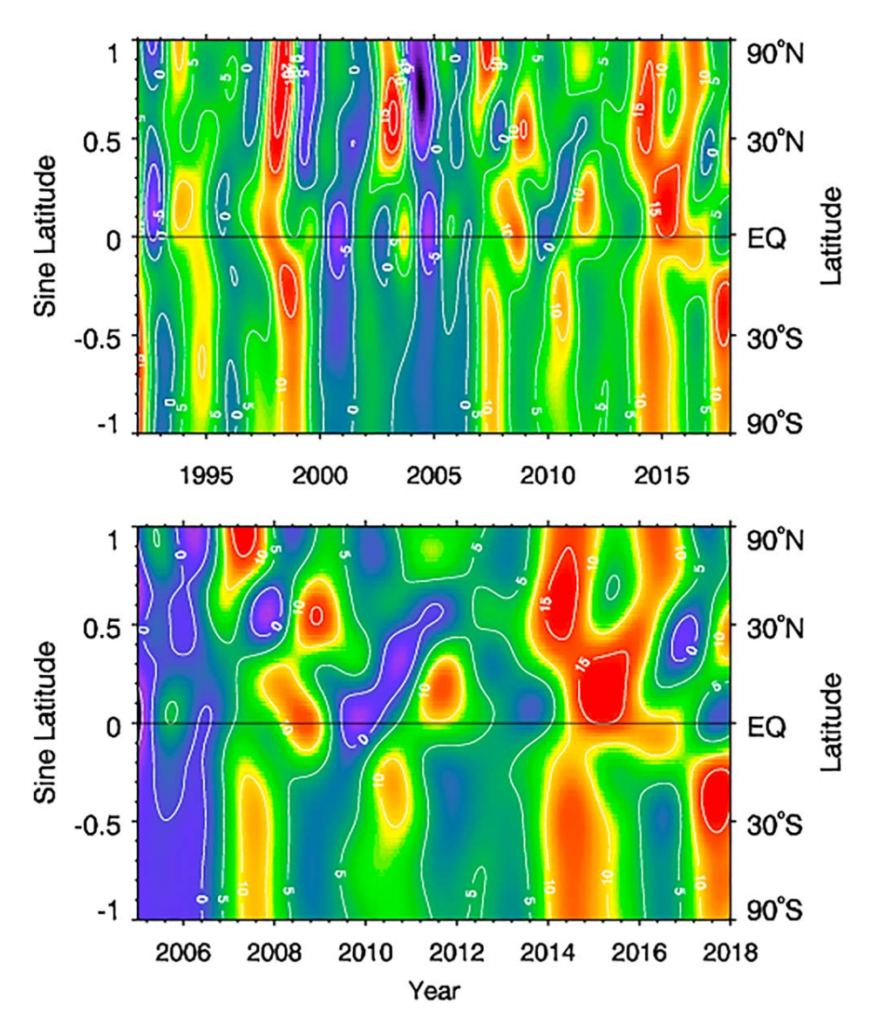

ABSTRACT: Atmospheric methane grew very rapidly in 2014 (12.7 ± 0.5 ppb/year), 2015 (10.1 ± 0.7 ppb/year), 2016 (7.0 ± 0.7 ppb/year), and 2017 (7.7 ± 0.7 ppb/year), at rates not observed since the 1980s. The increase in the methane burden began in 2007, with the mean global mole fraction in remote surface background air rising from about 1,775 ppb in 2006 to 1,850 ppb in 2017. Simultaneously the 13C/12C isotopic ratio (expressed as δ13CCH4) has shifted, has shifted, now trending negative for more than a decade. The causes of methane’s recent mole fraction increase are therefore either a change in the relative proportions (and totals) of emissions from biogenic and thermogenic and pyrogenic sources, especially in the tropics and subtropics, or a decline in the atmospheric sink of methane, or both. Unfortunately, with limited measurement data sets, it is not currently possible to be more definitive. The climate warming impact of the observed methane increase over the past decade, if continued at >5 ppb/year in the coming decades, is sufficient to challenge the Paris Agreement, which requires sharp cuts in the atmospheric methane burden. However, anthropogenic methane emissions are relatively very large and thus offer attractive targets for rapid reduction, which are essential if the Paris Agreement aims are to be attained.

SIGNIFICANCE: The rise in atmospheric methane (CH4), which began in 2007, accelerated in the past 4 years. The growth has been worldwide, especially in the tropics and northern midlatitudes. With the rise has come a shift in the carbon isotope ratio of the methane. The causes of the rise are not fully understood, and may include increased emissions and perhaps a decline in the destruction of methane in the air. Methane’s increase since 2007 was not expected in future greenhouse gas scenarios compliant with the targets of the Paris Agreement, and if the increase continues at the same rates it may become very difficult to meet the Paris goals. There is now urgent need to reduce methane emissions, especially from the fossil fuel industry.

Frackalicious!