Big cities, bright lights and up to 1 billion bird collisions each year in the U.S.

By Lindsey Feingold

7 April 2019

(NPR) – Up to 1 billion birds die from building collisions each year in the United States, and according to a new study, bright lights in big cities are making the problem worse.

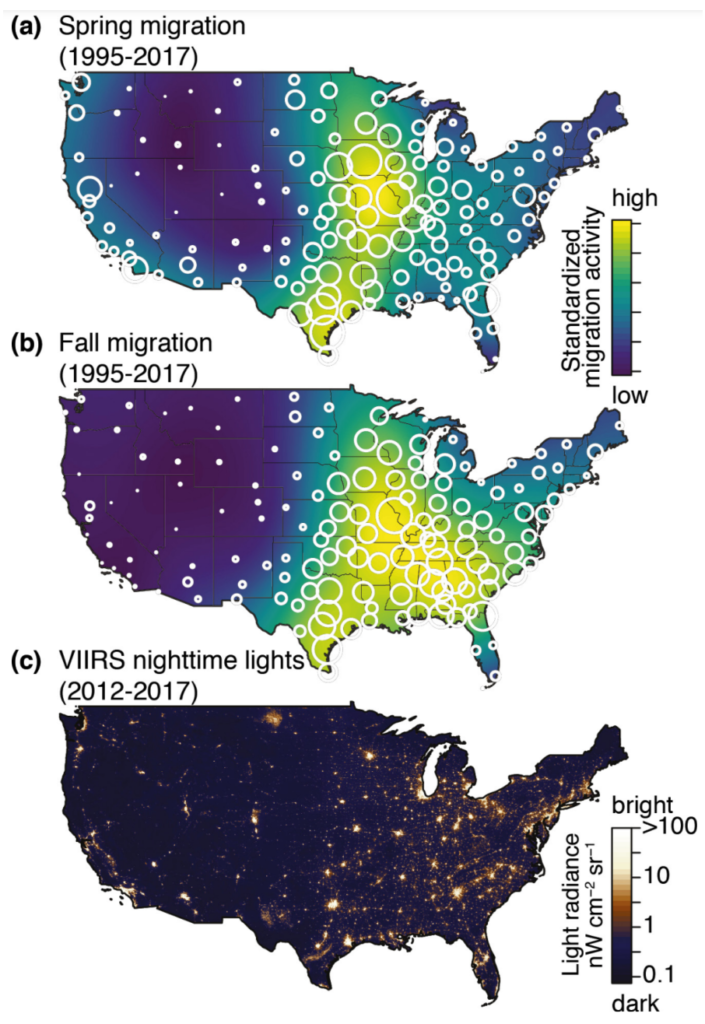

The study, published this month in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, examined two-decades of satellite data and weather radar technology to determine which cities are the most dangerous for birds. The study focused on light pollution levels, because wherever birds can become attracted to and disoriented by lights, the more likely they are to crash into buildings.

The study found that the most fatal bird strikes are happening in Chicago. Houston and Dallas are the next cities to top the list as the most lethal. One of the study’s authors, Kyle Horton, a postdoctoral fellow at Cornell University, called the cities a “hotspot of migratory action,” adding, “they are sitting in this primary central corridor that most birds are moving through spring and fall.”

New York City, Los Angeles, St. Louis, and Minneapolis are also dangerous cities for birds, all in the top 10 of the list for both migration periods.

Collisions are the most prevalent during the two migration periods, one in the spring and one in the fall. More than 4 billion birds migrate across the United States per migration period, according to Horton.

For Chicago, more than 250 different bird species migrate through the city, adding up to 5 million overall for each migration period.

“Many of these birds are already in serious decline for other reasons,” said Annette Prince, director of the Chicago Bird Collision Monitors, a local conservation group. “So when they’re hitting buildings, this is adding to the loss of the healthy members of their species by needless collision.”

Prince’s organization finds 5,000 to 6,000 birds per year in the 1-square-mile they search in downtown Chicago. Sixty percent of the birds they find are dead upon impact.

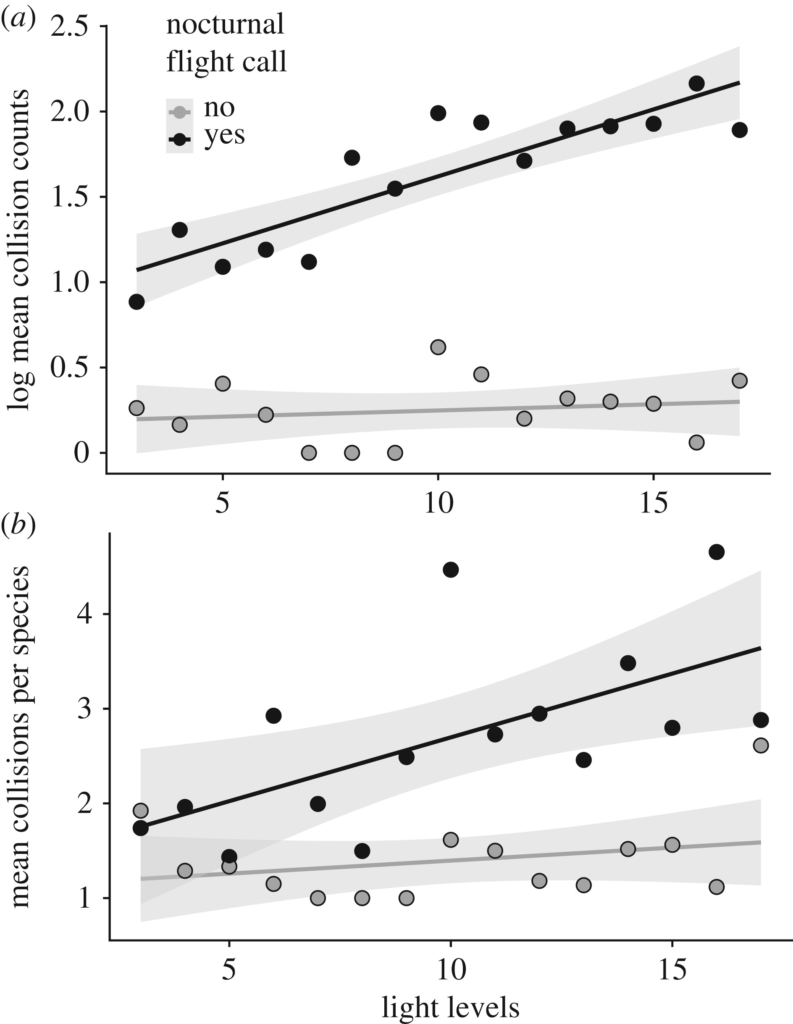

Another study published last week found that some bird species are more likely to fall suspect to building collisions. Songbirds that produce faint chirps – called flight calls – during nighttime migration collide with lit buildings more often than other species that don’t produce the chirps, according to a study by researchers at the University of Michigan. This is because data shows the birds disoriented by the artificial light send out flight calls, luring other birds to their inevitable death. [more]

Big Cities, Bright Lights And Up To 1 Billion Bird Collisions

ABSTRACT: Building collisions, and particularly collisions with windows, are a major anthropogenic threat to birds, with rough estimates of between 100 million and 1 billion birds killed annually in the United States. However, no current U.S. estimates are based on systematic analysis of multiple data sources. We reviewed the published literature and acquired unpublished datasets to systematically quantify bird–building collision mortality and species-specific vulnerability. Based on 23 studies, we estimate that between 365 and 988 million birds (median = 599 million) are killed annually by building collisions in the U.S., with roughly 56% of mortality at low-rises, 44% at residences, and <1% at high-rises. Based on >92,000 fatality records, and after controlling for population abundance and range overlap with study sites, we identified several species that are disproportionately vulnerable to collisions at all building types. In addition, several species listed as national Birds of Conservation Concern due to their declining populations were identified to be highly vulnerable to building collisions, including Golden-winged Warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera), Painted Bunting (Passerina ciris), Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis), Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), Kentucky Warbler (Geothlypis formosa), and Worm-eating Warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum). The identification of these five migratory species with geographic ranges limited to eastern and central North America reflects seasonal and regional biases in the currently available building-collision data. Most sampling has occurred during migration and in the eastern U.S. Further research across seasons and in underrepresented regions is needed to reduce this bias. Nonetheless, we provide quantitative evidence to support the conclusion that building collisions are second only to feral and free-ranging pet cats, which are estimated to kill roughly four times as many birds each year, as the largest source of direct human-caused mortality for U.S. birds.

Bright lights in the big cities: migratory birds’ exposure to artificial light