Sea turtles are being born mostly female due to warming – “I can’t deny it: seeing those results scared the crap out of me”

By Craig Welch

4 April 2019

(National Geographic) – She started out studying tree-climbing marsupials, but only after she applied what she knew to marine reptiles did Camryn Allen actually get worried.

Allen, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Hawaii, had spent her early career using hormones to track koala bear pregnancies. Then she started using similar techniques to help colleagues quickly answer a surprisingly hard question: whether a sea turtle is male or female.

You can’t always tell which is which just by looking. That often requires laparoscopy, viewing the turtle’s internal organs by inserting a thin camera. Allen figured out how to do it using blood samples, which made it easier to check lots of turtles quickly.

That mattered because the heat of sand where eggs are buried ultimately determines whether a sea turtle becomes male or female. And since climate change is driving up temperatures around the world, researchers weren’t surprised that they’d been finding slightly more female offspring.

But when Allen saw results from her research on Raine Island, Australia—the biggest and most important green sea turtle nesting ground in the Pacific Ocean—she realized how serious things might get. Sand temperatures there had increased so much, she and a team of scientists reported last year, that female baby turtles now outnumber males 116 to 1.

“I can’t deny it: seeing those results scared the crap out of me,” Allen says.

Sea turtle life is hard enough on its own, and humans were already making it even harder. [more]

Sea turtles are being born mostly female due to warming—will they survive?

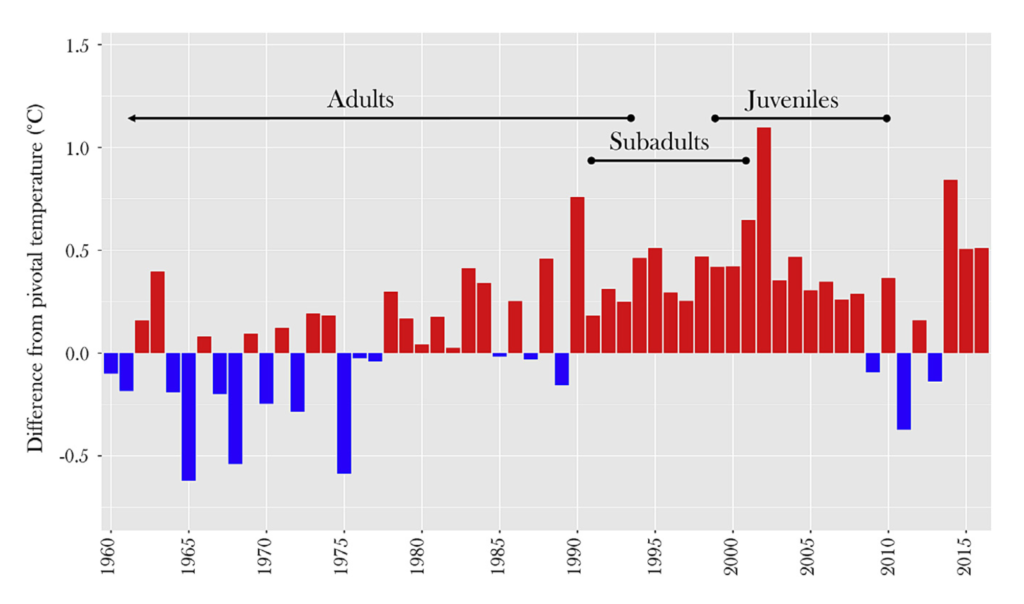

ABSTRACT: Climate change affects species and ecosystemsaround the globe [1]. The impacts of rising temperature are particularly pertinent in species with temper-ature-dependent sex determination (TSD), where the sex of an individual is determined by incubation temperature during embryonic development [2]. In sea turtles, the proportion of female hatchlings increaseswith the incubation temperature. With average global temperature predicted to increase 2.6°C by 2100 [3],many sea turtle populations are in danger of high egg mortality and female-only offspring production. Unfortunately,determiningthe sex ratios of hatchlings at nesting beaches carries both logistical and ethical complications. However, sex ratio data obtained at foraging grounds provides information on the amalgamation of immature and adult turtles hatched from different nesting beaches over many years. Here, for the first time, we use genetic markers and a mixed-stock analysis (MSA), combined with sex determination through laparoscopy and endocrinology, to link male and female green turtles foraging in the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) to the nesting beach from which they hatched. Our results show a moderate female sex bias (65%–69% female) in turtles originating from the cooler southern GBR nesting beaches, while turtles originating from warmer northern GBR nesting beaches were extremely female-biased (99.1% of juvenile, 99.8% of subadult, and 86.8% of adult-sized turtles). Combining our results with temperature data show that the northern GBR green turtle rookeries have been producing primarily females for more than two decades and that the complete feminization of this population is possible in the near future.

Environmental Warming and Feminizationof One of the Largest Sea Turtle Populationsin the World